|

Teaching the basics of music doesn’t always have to take place in school. While formal music education programs are vital for giving children an appreciation of music as one of the quintessential human activities—and are certainly needed when children hope to pursue a musical career—parents and families can provide numerous informal opportunities to develop their children’s musical gifts. Music has an innate and immediate appeal to almost all children, so get creative and make it one of the focal points in your family life. The following suggestions, advocated by a variety of music teachers and family educators, can help point you in the right direction: Turn “trash” into treasure. Use ordinary items found around your home, office, or yard to produce interesting and captivating sounds. For example, you can start an entire percussion section with a few kitchen and garden tools: Pots and pans, lids, watering cans, metal or wooden spoons, empty jugs, unbreakable bowls, water glasses, and other items can produce a wide variety of tones. Try banging the sturdier items together, or beat them with spoons or ladles to make an impromptu drum set. Fill a series of glasses with different levels of water and gently strike them with a spoon. This latter activity is a wonderful chance to create your own STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts, and math) lesson, as you and your child see firsthand how the amount of water in a glass affects the speed at which sound waves travel and therefore the pitch of the resulting sound. Other items that can produce a variety of sounds for your child’s enjoyment include that bubble wrap you were about to throw away, pens and pencils, or even crumpled-up newspaper or wrapping paper. Get crafty.Making his or her own musical instruments together with adults can add to the fun of a child’s musical education. In addition, reusing items that you would have thrown away can help your family gain a greater appreciation of the need for recycling and purposeful spending. Numerous websites, put together by parents and teachers, offer lively selections of ideas and directions for making a rich array of simple instruments. An old box that may once have held tissue paper can be fitted with rubber bands to fashion a simple guitar. Plastic Easter eggs can be decorated and filled with dry rice, beans, or peas to become wonderful shaker instruments. A paper plate with jingle bells attached to it with string becomes a tambourine. And balloon skins stretched over the tops of a series of tin cans can become an exceptional set of drums. After you create your own instruments, practice them together. See how many sounds you can coax them to produce, and even try writing and performing a musical composition using only the instruments you have made. Experiment together while emphasizing to your child that improvisation and exploration are more important than “perfection.” Connect with real musical instruments.If you can buy or borrow real musical instruments, bring them into your home whenever possible. Young children are likely to be especially tactile, so let them experience what a drum set, a clarinet, or a flute feels like in their hands. A visit to a local museum that has a music exhibit, or to a music store or university music department, can also provide this experience. Investigate whether your community offers musical instrument lending libraries, which are designed to provide access to music education for all people, regardless of income. Such libraries are available in some locations in the United States, but residents of Canada are especially fortunate. Toronto, for example, recently initiated a musical instrument lending program through its public library system. Library patrons can check out violins, guitars, drums, and other instruments, free of charge. Listen together.Bring live and recorded music from as many cultures and time periods as possible into your home. Practice your listening skills, and see if you and your child can recognize the sounds of the different instruments in a composition. Encourage your child to catch the beat by clapping, tapping a foot, or creating a dance in time with the music. Hit the books.Bring home a variety of music-themed books, including picture storybook classics like Zin! Zin! Zin! A Violin, written by Lloyd Moss and illustrated by Marjorie Priceman; or The Philharmonic Gets Dressed by Karla Kuskin, with pictures by Marc Simont. Older children will also find plenty of music-themed fiction in titles such as Bud, Not Buddy by Christopher Paul Curtis and The Trumpet of the Swan by E. B. White. Your local bookstore or public library will likely offer all of these, and many others, as well as informational books about music and biographies of great musicians. Unite music and art.You can also look for coloring books that feature images of musical instruments or music performances. Additionally, a simple internet search using the keywords “musical instruments” and “coloring pages” will yield many free images to download and print for your child to decorate. Creating visual representations of musical instruments and concepts will provide a multi-sensory experience that can deepen your child’s connection to the related art of music.

Whether tone poems are enjoyed in a concert hall or played in a simplified arrangement in school or at home, they offer young music students a rich variety of musical experiences. A tone poem is a musical composition designed for a full orchestra. It is designed to evoke, through the choice of instrumentation, tempo, and arrangement, concrete images and storylines in the minds and hearts of listeners. The titles of many tone poems further help the listener in that they acknowledge a composition’s roots in a famous legend, poem, picture, place, or historical event. A tone poem can conjure up visions of majestic mountains, forests, and waterways; knights on horseback gliding over desert sands; the appearance of magical beings, or the tender feelings between two lovers. And a favorite tone poem can make audiences feel transported, mentally and emotionally, to long-past heroic ages, or into the pages of beloved works of literature. Hungarian composer Franz Liszt is often credited with inventing the form of the tone poem, also known as the symphonic poem, in the mid-19th century. In this era of romanticism, revolution, and rising national consciousness, the form flourished. By the early 20th century, composers such as Igor Stravinsky were still writing richly orchestrated tone poems. However, the form began to shift toward using this type of colorful music as a background for dance performances, rather than as single-unit orchestral pieces. Here are brief summaries of what makes only a few of the best-known tone poems memorable: 1. The MoldauCzech composer Bedřich Smetana completed “The Moldau” after only 19 days of work in 1874. Since then, its central melody has become an iconic national symbol. The piece is one part of a six-section suite titled My Country, in which the deeply patriotic composer depicted the natural beauty and the rich cycle of history and myth of his native land. “Moldau” is the German name for the Vltava River, which flows from high forested mountains through the country lowlands and straight through the center of Prague. Smetana’s piece is by turns mystical, forceful, lively, and majestic, as it conjures up, first, the river’s quiet patter, then its sweep through a folksong-filled plain, to its destination near the capital, the royal seat of the Bohemian kings. 2. ScheherazadeRussian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov debuted his orchestral suite Scheherazade in 1888, offering audiences a collection of musical trips to the stories of the Arabian Nights. The deep, bold opening notes paint a powerful picture of Sultan Shahryar, and the sinuous lilt of the violin portrays his wife, the storyteller Scheherazade, with the later musical themes unfolding the stories she tells like the unrolling of a magic carpet. The four movements of the suite tell the story of Sinbad and his ship on the ocean; the “Tale of the Kalendar Prince,” bringing out the full capacity of the woodwinds to evoke an air of mystery; the tender and richly soulful romance of the story of a young prince and princess; and a finale that brings in themes from each of the previous sections, culminating in vivid images of a festival and the destruction of a ship on a wild, tempestuous sea. 3. FinlandiaIn 1899, Finnish composer Jean Sibelius composed and premiered his now world-famous tone poem “Finlandia” as part of a larger suite. Like Smetana, Sibelius was a patriot who used his music to challenge the rule of an empire over his small country. “Finlandia” was, in fact, originally written to be performed at an event protesting the Russian tsar’s censorship of the Finnish press. The work begins with the boom of timpani and brass to establish a somber and foreboding setting. As woodwinds and strings enter the musical conversation, they help to weave the type of stately atmosphere found in a king’s great hall. After a burst of forceful sound bringing in the sense of the whirlwind of struggle animating the Finnish people, the mood lifts. The piece concludes on drawn-out notes evoking a deep sense of serenity and majesty, as if listeners were looking down on sweeping vistas of dark-green Finnish forests. Soon after its composition, the central theme of “Finlandia” became popular worldwide, with many American communities using the melody for songs honoring cities, schools, and other organizations. 4. Fantasia Walt Disney’s 1940 full-length orchestral cartoon movie masterpiece Fantasia is a contemporary tone poem in itself. The film incorporates Disney’s retellings and re-imaginings of the stories behind several of the best-known symphonic works, including French composer Paul Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. In Disney’s version, Mickey Mouse is the hapless student of magic pursued by a pack of enchanted brooms.

Dukas’ original soundtrack debuted in 1897. He based it on a folkloric tale by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, one of the towering figures in the European literature of the Enlightenment. Dukas’ composition closely follows the sequence and spirit of Goethe’s piece by offering an opening that paints a picture of quiet, but magic-filled domesticity in the sorcerer’s workshop. But then the apprentice enters, represented by a leitmotif uniting oboe, flute, clarinet, and harp. A burst of timpani perhaps signals a stroke of enchantment. Then, through the composer’s use of a triple-time march, the sorcerer’s army of brooms comes lumbering, and then sprinting, to vivid life, carrying one bucket of water after another. Dukas masterfully uses strings to conjure up the flooding cascade of water that ensues before the sorcerer, accompanied by the gloomy moans of the bassoon, returns to chase away all the mischief. At Music Training Center (MTC) in Philadelphia, children can take lessons in music and voice training. They can also participate in an a cappella vocal ensemble, Rock Band classes, or a number of high-quality musical theater productions. Over the years, Music Training Center has nurtured the talents of a number of promising young musicians and performers. The musical theater component is one of the organization’s signature programs. Kids in the upper elementary, middle school, and early high school grades can participate in its Main Stage musical production. Younger kids work on their own Junior Stage and Mini Stage productions. Popular musicals serve as an excellent way to engage kids with learning the basics of musical theater stagecraft. Experts in the performing arts have noted musical theater’s ability to develop a wide range of essential talents and skills in children who are considering making any branch of acting or performing a lifelong career. Further, musical theater training can lay the foundation for the kind of self-confidence, physical and mental stamina and agility, and personal presentation skills that will enhance a young person’s performance in any other type of career later on. There are many reasons to encourage your child to participate in musical theater. Here are four: 1. Musical theater programs are available throughout the countryThe MTC program is only one of many across the country that focus, either year-round or as a special summer experience, on the wealth of benefits that participation in a musical theater production can provide for children. The Performers Theatre Workshop in New Jersey, the Music Institute of Chicago, and San Francisco Children’s Musical Theater are only a few more examples of organizations that offer this kind of vibrant and engaging—and potentially life-changing—programming. 2. Musical theater helps teach movement, communication, and confidence.For example, kids who participate in musical theater training learn a whole set of movement skills. These skills can improve coordination, kinetic awareness, and overall fitness. In addition, training the voice to perform songs in a musical theater production tends to strengthen the vocal chords. They also benefit the performer’s overall voice presentation. This is a helpful tool for leaders and communicators in any field. Experts in teaching musical theater additionally point out that confidence is among the main takeaways from participation for many kids. Musical theater can take performers far beyond their familiar comfort zones. A student who primarily views herself as an actor might be asked to sing in a particular production. Another who thinks of himself only as a dancer might be called on to learn and speak lines of dialogue to convey an emotional experience. These activities might at first give young performers a case of nerves. Ultimately, however, this type of multifaceted training can open doors onto new ideas, build new skills, and create a sense of accomplishment in ways that stay meaningful over a lifetime. 3. Musical theater boosts self-esteem. One dissertation-related study, published in 2017 under the auspices of Concordia University-Portland, found that music and theater studies, individually, offer enormous potential. They can help middle school students develop their self-esteem and their scholastic achievement. The study goes even further by exploring the ways in which the combination of the two subjects in musical theater can lift up middle school students’ sense of self-worth and facilitate their achievement in a number of ways. In this particular study, about a dozen suburban private school students in Minnesota took part in staging a musical theater event. The researcher used direct observation, interviews, school records, and Likert scale surveys to gauge the degree to which the students engaged in a positive or negative way with the experience. The study concluded that if a student came into the production with already-high levels of self-esteem, he or she did not experience an additional boost of self-esteem from participation. On the other hand, if a student had a lower level of self-esteem before the production, he or she was more likely to develop more openness to being flexible and taking on novel tasks during the course of the production. These students also showed increased comfort with the process of change during the production. 4. Musical theater is fun!One remaining important aspect of performing in musical theater: it's fun. Kids of all ages enjoy meeting familiar or intriguing characters from movies, books, or TV shows translated onto the stage.

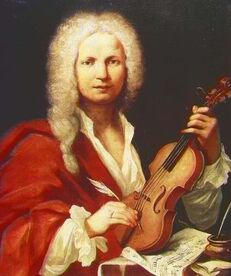

When they take on the personas of these characters themselves, they can find creative new ways to express themselves. They can also deepen their awareness of their own emotions and let their imaginations take them on new adventures. According to the National Association for Music Education, there are a few important qualities that make for an outstanding music teacher. These include strong communication skills, an understanding of how to make learning the rudiments of music worthwhile, the ability to command respect, and a capacity for forging emotional connections with students. Any list of the world’s notable music teachers throughout history would include the following talented individuals, who were also accomplished composers. Read on to learn about their lives, their music, and what they taught their students. Antonio Vivaldi – Leader of a girls’ orchestra Image by Wikipedia Image by Wikipedia By the time of his death in the mid-18th century, Italian composer and priest Antonio Vivaldi had authored hundreds of pieces of church music, concerti, operas, and other compositions. Best known today as the composer of The Four Seasons series of concerti, he exemplified the Baroque sensibility. His music is filled with complex, bravura passages that highlight the solo capabilities of individual instruments. Vivaldi was also a teacher, working at several different schools of music over his career. When he was just 25 years old, he became master of violin with the Ospedale della Pietà, a Venetian school for orphaned children. While serving in this capacity over some 30 years, he managed to compose the bulk of his major creative works. At the Ospedale, the boys were taught skilled trades, and the girls learned music. Vivaldi’s leadership of the girls’ orchestra and chorus brought international fame to the school. The group performed at religious services and often at special events intended to make an impression upon powerful visitors. The girls performed, however, concealed behind a set of gratings, supposedly for the purpose of safeguarding their modesty. Antonio Salieri – Villainous or defamed?Thanks in part to Milos Forman’s movie Amadeus, the dominant image of Antonio Salieri is a jealous villain who helped to drive his rival Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to an untimely death—or possibly poisoned him. But recent investigations have shown that there was likely far less substance to the feud between the two men. Newer biographies and recent performances and recordings of his music, including an album by Cecilia Bartoli, are beginning to show us that Salieri was a talented composer, with a personality that may have been cantankerous. Newer research also shows that he was viewed by contemporaries as a generally friendly, industrious, and occasionally even humorous man. Salieri’s creative output includes several operas in multiple languages, as well as chamber music and works for sacred occasions. Only six years Mozart’s senior, Salieri would live to the age of 74 and eventually see his powers as a composer dwindle, though he took on a roster of exceptionally gifted pupils. These included Ludwig van Beethoven, the German operatic composer Giacomo Meyerbeer, Franz Liszt, and Franz Schubert. Historians recount the story of how Salieri spotted the seven-year-old Schubert’s talent and began teaching him the basics of music theory. After Mozart’s death, Salieri even instructed Mozart’s young son. In 2015, a short composition created jointly by Mozart, Salieri, and a third composer was unearthed from the archives of the Czech Museum of Music. The following year, a harpsichordist in Prague gave the work its first public performance in 230 years. Nadia Boulanger – A “hidden figure” in music Image by Wikipedia Image by Wikipedia Nadia Boulanger earned international fame as a conductor and teacher of musical composition. Born in 1887, she was the daughter of Ernest Boulanger, a renowned voice teacher at the Paris Conservatory. She studied at the conservatory with composers Charles-Marie Widor and Gabriel Fauré, then began a career teaching both private lessons and classes. At age 21, she received a second place honor in the Prix de Rome competition for a cantata she had composed. Boulanger’s sister, who died young, was also a talented composer. In fact, after her sister’s death, Boulanger deemed her own work as a composer to be of no further use and stopped creating entirely. However, she continued to both promote her sister’s work and to teach others. By the early 1920s, she was working at the American Conservatory at Fontainebleau. Boulanger went on to become the first female conductor to work with the New York Philharmonic and other American orchestras. She taught in the Washington, DC area during the Second World War. In 1949, she earned the position of director of the American Conservatory. Boulanger’s first American student was Aaron Copland, and she later taught Virgil Thomson, Leonard Bernstein, Philip Glass, and a host of other noted composers. She lived to be 92 years old, but never in her long life wrote a textbook outlining her ideas on music theory. Rather, she exerted a strong and nurturing personal influence on her pupils. She worked to give them an in-depth understanding of the technicalities of music while enhancing their individual gifts of composition and expression. Zoltán Kodály – The centrality of the voiceZoltán Kodály, one of the best-known 20th century Hungarian composers, was also a scholar of the folk music of his country. Along with his contemporary Béla Bartók, he became one of the foremost collectors of traditional Hungarian songs. Kodály’s own creative compositions include the massive Psalmus Hungaricus, first performed in 1923 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the joining of the cities Buda and Pest.

Kodály was also a contemporary of Boulanger and studied with Widor in Paris. He achieved renown for establishing the building blocks of what is today known as the Kodály Method, used by music teachers around the world. The Kodály Method works with the understanding that young children learn music best by doing, and that the body of traditional songs and dances of their own countries should form the core of their musical education, supplemented with the folk music of numerous other cultural traditions. Kodály’s system additionally puts great emphasis on the power and flexibility of the human voice as the first musical instrument. His method stresses singing as the best way to develop musical understanding and skill. Zoltán Kodály ranks among the foremost music educators of all time. He was born in what is now Hungary in 1882, and, well before his death in 1967, had earned an international reputation as a composer of highly original pieces, a scholar of folk music, and the originator of the method of music instruction that continues to bear his name. The Kodály Method has become widely known among music educators for its dynamic, interactive, and movement-oriented approach to instruction for children. It incorporates a set of proven techniques that foster the unfolding of a child’s natural gift for musicianship. The approach, which focuses on creativity and expressiveness, has demonstrated its relationship to the traditional ear-training method. During Kodály’s lifetime, his influence was felt throughout Europe and the world as an instructor who taught numerous teachers, and his method continues to be popular today. A young composer and teacher finds his vocation.In his youth, Kodály studied the piano, cello, and violin. When he was in his teens, his school orchestra performed several of his compositions. In 1900, he enrolled at the University of Sciences, located in Budapest, and became a student of contemporary languages and philosophy. He went on to study composition at Budapest University, but before graduating, he spent a year criss-crossing Hungary on a search for sources of traditional folk songs. He then centered his university thesis on the structural properties of Hungarian folk songs. Shortly after graduating in 1907, Kodály accepted a position in Budapest teaching the theory and composition of music at the Franz Liszt Academy of Music. He would remain on the school’s faculty for 34 years. Even after retiring, he returned to the school in 1945 to serve as a director. His dedication was driven by a desire to preserve his country’s musical culture, particularly in light of the unrest that characterized its political scene in his time. Before he entered into his duties at the Liszt Academy, Kodály met fellow Hungarian composer and folk music collector Béla Bartók. Together they published, over a span of 15 years, a folk song series based on their research. The series became the core of Hungary’s authoritative corpus of popular music. A 20th century master of styles.Kodály’s own style as a composer was anchored in the folk music that he loved and had a richly Romantic tone, while incorporating classical, modernist, and impressionistic techniques, as well. His best-known works include a concerto for orchestra, chamber pieces, a comic opera, groups of Hungarian dances, and the 1923 work Psalmus Hungaricus, which was created to honor the 50-year anniversary of the fusion of Buda and Pest into a single city. The piece brought him international fame and conferred upon him the mantle of musical spokesman for the culture of his country. As both a scholarly writer and musician, Kodály in his later years penned numerous books and articles on Hungarian folk songs. An evolving method.One story, perhaps apocryphal, has it that Kodály was so disappointed when he heard a group of schoolchildren perform a traditional song that he decided to improve the state of Hungarian music instruction himself. Kodály put nearly as much emphasis on developing his music education program as on his own creative works of composition. His interest in the issue of music teaching was intense, and he produced a variety of educational publications designed to expand the horizons of teachers. Kodály thought that music was among the vital subjects that should be required in all systems of primary instruction. He further stipulated that it be presented in a sequential framework, with one step logically leading to the next. He believed that students should enjoy learning music, that the human voice is the premier musical instrument, and that the most accessible teaching method incorporates folk songs in a child’s original language. Kodály himself was primarily the originator of his eponymous method, generating numerous ideas and principles that now form the basis of its core teachings, as used in classrooms today. However, it was left to the Hungarian teachers that he trained and inspired to fully develop it over time, often under his direct guidance. The Kodály Method serves as a comprehensive system of training musicians in the reading and writing of musical notation, as well as the acquisition of basic skills. In doing so, it draws upon proven techniques in the field of music instruction. It is also in itself a philosophy of musical development that emphasizes the experiences of each learner. The importance of the human voice. One of the basic principles of the method is singing, which Kodály himself viewed as the core of his system. The Kodály Method stresses that, first, a child should learn to love music for the sheer fact that it is a sound made by other human beings, and one that makes life richer and happier. Teachers of the method also emphasize the human voice as the one musical instrument accessible to most people around the world as a common means of expression. One reason why singing has such a central role in the method is the idea that the music one creates by oneself is better retained and provides a greater feeling of pride and personal accomplishment. The Kodály Method therefore places singing—and reading music—ahead of any sort of training on an instrument. Kodály also believed that singing was the best means of training the inner musical ear. The content of any classroom based on the Kodály Method will consist largely of folk songs from a child’s own heritage, as well as those of other cultures. Classic childhood rhymes and games will also be included, as will pieces of great music produced in any time and place. Continuing the work. Since 2005, the Liszt Academy has hosted the Kodály Institute, which provides advanced-level music education training for teachers, based on the Kodály Method. The institute works as the guiding force for the entire set of music instruction programs of the academy. In addition to its teacher-training programs, the institute offers the International Kodály Seminar every two years. Participation in the seminar is open to music teachers around the world and coincides with an international festival of music. The next seminar is scheduled to take place in July 2019. For more information, visit Kodaly.hu.

Children love music and picture books. This means that parents and educators are constantly on the look-out for new books to share that nourish a love for both music and reading. Today’s picture book writers and illustrators are producing work that is distinguished by rich literary and visual imagination. Among these treasures are a number of works that convey, in the sounds of their vocabularies and through the skill of their illustrations, what it feels like to make and enjoy music. Here are only a few of the best picture books published in 2018 whose storylines focus specifically on music. All of these titles will be found in most online and bricks-and-mortar bookstores as well as in many public libraries. 1. The Bunny BandThe Bunny Band was written by Bill Richardson, illustrated by Roxanna Bikadoroff, and published by Groundwood Books. It presents young readers and their families with a delightful adventure into the ways in which music can facilitate even the most unlikely friendships. Lavinia is a badger who cherishes her carefully tended vegetable garden. Suddenly, she realizes that an unknown someone has been eating her lettuce and taking her other produce. She sets out to catch the thief and discovers that it is a bunny. The angry badger threatens to put him into her stew pot, but the little rabbit begs her to spare him. In return, he promises her a mysterious reward. After Lavinia shows mercy on the repentant thief, she receives a surprise. The next evening, in the moonlight, her new friend returns, bringing with him lots of other bunnies, each one bringing a musical instrument. This lively bunny band pours delightful music into Lavinia’s garden with a host of banjos, ukuleles, trumpets, drums, and even a set of bagpipes. Much to the badger’s surprise, the music makes the garden grow! In thanks, Lavinia treats all the bunnies to a surprise: a feast made from the produce in her garden. The book’s rich and whimsical illustrations show the individual personalities of Lavinia and the entire bunny musical troupe. They are engaging for readers of all ages and convey in line and color the spirit of joyful music shared among friends. 2. Khalida and the Most Beautiful SongKhalida and the Most Beautiful Song, written and illustrated by Amanda Moeckel and published by Page Street Kids, is a symphony in pink and purple watercolors. Khalida is an overscheduled child. She wants nothing more than to capture the elusive song that whispered briefly to her one evening. But no matter how she tries, the time and place are never right. Her busy life comes between her and her ability to sit down at the piano to do the creative work she longs for. Even through adversity, Khalida persists in her quest for the essence of the song. Her perseverance is at last rewarded. The young girl’s love of music, and the beauty of the song she is finally able to catch, are made palpable through Moeckel’s flowing, elegant pictures. These serve as a visual counterpoint to the musical flow of the text. 3. New York MelodyWith its delicate tracery of laser-cut shadow images and sharp black-and-white shapes, New York Melody was written and illustrated by Helene Druvert and published by Thames & Hudson. It is a keepsake book to treasure. The simple story begins at Carnegie Hall. A single musical note on a page of sheet music gets free of its comrades and goes off on its own to explore the wonders of New York City. It drops in on a secret little jazz club, pays a visit to Broadway, and at last finds an island of peace as it joins in with a guitar player in Central Park. The guitar’s melody catches the ear of a passing cyclist, who carries the tune all over the city, causing passersby to pause in enchantment. Along its journey, the note works in tandem with numerous instruments, including a saxophone, a double bass, and a trumpet. The depiction of this last instrument, in glowing, vivid gold, presents a visual delight amidst the book’s otherwise monochromatic palette. Druvert’s book has a genuine ability to make the aural delights of music palpable through words and pictures. Additionally, it captivates readers with a tour through famous—and not-so-famous—New York landmarks. 4. The DamDavid Almond is best known for Skellig and other darker, edgier novels for older children. He worked with illustrator Levi Pinfold and publisher Candlewick Studio to create in The Dam a haunting tribute to the power of music to memorialize and recreate a lost world.

The book is based on the true story of the creation in Northumberland, in the 1970s, of the Kielder Water reservoir and dam. It resulted in the largest man-made lake in the United Kingdom. The region has historically been rife with legends and home-grown music produced by the people who lived on farmsteads all over the valley. In Almond’s re-imagining, a father and his young daughter return to the village after it has been abandoned. They know that the dam about to come into being will flood the land they love, burying the many abandoned stone houses under the waters. In Almond’s story, the father and daughter go from empty house to empty house, filling them for one last time with music from the girl’s fiddle. Pinfold’s muted, elegiac art provides the perfect accompaniment for this tale of loss, remembrance, and finding emotional resilience through the creation and performance of music. Historians point out that, by the time the real dam at Kielder Water was constructed, the buildings had all been razed. However, The Dam’s vividly etched tribute to things lost will ring true for readers of all ages. Not even a sprawling dam and the rushing in of mighty waters, the book tells us, can still the human longing for creating new worlds—and remembering old—through music. Since ancient times, archeologists have discovered relatively few musical instruments and fragments of musical instruments. Yet each one of them tells us something important about the musical heritage of humanity. Learning about each of them can play an important role in teaching today’s young students about the joys and possibilities inherent in making music. A number of contemporary musicians recreate ancient instruments according to the best-available historical and musical information. Such instruments may be displayed in a museum, brought to school as a learning experience, or played in a performance. Here are a few of those instruments: 1. LyrePerhaps the ancient instrument that remains best-known to today’s audiences is the lyre. The stringed instrument was popular in ancient Greece. In fact, some commentators have described the lyre as the instrument that best illustrates the traditional character of Greece. Like the piano today, it was typically a central part of a student’s musical education. An ancient musician would play the lyre alone or as an accompaniment to singing or a poetry recital. The standard form of the lyre was two stationary upright arms—sometimes horns—with a crossbar connecting them. The instrument would be tuned by means of a set of pegs, which could be made of ivory, wood, bone, or bronze. Stretched between the crossbar and a stationary bottom portion were seven strings that varied in thickness, but which were typically all of the same length. A musician either plucked the strings by hand or used a plectrum. Closely related stringed instruments included the kithara, which also had seven strings; the phorminx, which had four; and the chelys, fashioned from tortoiseshell. In fact, ancient writers tended to use these four instruments interchangeably in variant retellings of different myths. A typical Greek myth states that the messenger god Hermes originated the lyre. Hermes instructed the sun god Apollo in how to play the instrument. Apollo became a master lyre player who in turn instructed the gifted musician Orpheus. 2. Syrinx The syrinx, also known as the Pan’s syrinx, the Pan flute, or—in modern times—the panpipes, is a wind instrument associated with the shepherd god Pan, as well as human shepherds. It was considered a rustic—not an artistic—instrument. The Greeks were likely the first to make use of the syrinx, which was made of between four and eight sections of cane tubing of different lengths, bound together with wax, flax, or cane. A syrinx player could produce a range of rich, low tones by blowing across the tops of the cane tubes. Thousands of years of Greek art frequently show images of the syrinx. Artistic depictions of mythological figures such as Hermes, Pan himself, and the satyrs—half goat, half man—often show them playing the syrinx. 3. SistrumThe sistrum was a percussion rattle known to be used by the ancient Egyptians and Greeks. It enabled musicians to create a backbeat accompaniment to the instruments carrying the tune, particularly during religious ceremonies. A sistrum could be fashioned from wood or clay, as well as metal. Its percussive pieces consisted of horizontally arranged bars and the moveable jingle parts assembled along them. The sistrum had a handle attached to this framework, and a musician shook it just like a rattle. The sistrum was chiefly associated in Egyptian culture with the mother goddesses Hathor and Isis. Ancient artwork shows musicians playing the sistrum in statues and figures on pottery. 4. Aulos and Double AulosThe aulos, a reed-blown wind instrument that resembles a modern flute, was among the most commonly used instruments in ancient Greece. Associated with the god of wine, Dionysos, it was a frequent accompaniment to athletic festivals, theater performances, and dinners and events in private homes. Like the contemporary flute, the aulos consisted of several individual sections that locked into place together. It could be made of bone, ivory, boxwood, cane, copper, or bronze. It also featured several different types of mouthpieces, which could produce various pitches. The ancient Greeks also made use of the diaulos—the double aulos—which was made by affixing two equal-sized or different-sized pipes together at the mouthpiece. If the two pipes were of uneven length, the resulting sound was enriched with a supporting melody line. The Greeks also sometimes used a strap made of leather to secure the pipes to a musician’s face for ease of playing. With its deep, resonant sounds, the diaulos typically functioned as a support for all-male choral performances. 5. Xun Among the oldest-known ancient Chinese musical instruments is the xun, a type of vessel flute that researchers believe dates back more than 7,000 years. Historians believe that the xun was among the most popular instruments of its time.

The xun was typically made of pottery clay and often featured depictions of animals. Offering a one-octave range, it was fashioned into the shape of an egg with a flat bottom and a number of fingerholes along its body. A player could produce sound by blowing across the top mouthpiece. Examples of the xun have been excavated at archeological sites in various parts of China, with some of the later finds formed to resemble fruits or fish. Some of the more intricately decorated xun created over the centuries have become highly prized pieces in museums and private collections. Ancient writings mention the xun, often accompanied by the chi, which was a side-held flute typically made of bamboo. Musicians usually employed the xun as a component of a traditional ritual ensemble. The xun was regularly used until about a century ago, and has recently experienced a revival. A contemporary version, with nine holes is used in some Chinese orchestras today. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City is the home of countless artistic, historic, and cultural treasures from all over the world. Music educators, music students, and their families traveling to the city should all consider putting the Met’s vast collections of musical instruments on their day-trip itineraries. The museum’s 5,000 instruments, with some more than 2,000 years old, come from all over the world. Curators have selected each one for its visual appeal and the quality of its sound, as well as for its importance in the entire history of humanity’s interactions with music. Here are notes on only a few of the impressive items owned by the Met. 1. One of the first pianosThe highlights of the Met’s music collections include a grand piano dating from about 1720 in Florence, Italy, and constructed by Bartolomeo Cristofori. Scholars generally credit Cristofori with the invention of the piano, based on his functional hammered keyboard. The Met’s Cristofori piano is the oldest of the three known to be in existence, and it is fashioned chiefly from cypress wood and boxwood. Cristofori’s design for his hammer mechanism was so well-constructed and musically flexible that no other inventor was able to devise a comparable one for 75 years. Many of today’s musicologists believe that the rich harmonies and tonal complexity of the contemporary piano trace directly back to his instrument. 2. A symphony in stringsThe Met is home to a viola d’amore made by Giovanni Grancino in Milan in 1701. With the exception of the legendary violin-makers of the town of Cremona, Grancino is often viewed by musicologists as the foremost practitioner of his art working in the early 18th century. The viola d’amore is one of the members of the viol family, which includes the violin. The Met’s example is created out of spruce, ebony, and maple woods, as well as iron and bone. Grancino’s instrument features metal strings, a characteristic of early viola d’amores. Later pieces went on to use sympathetic strings. The metal strings were noted for giving the instrument its “sweetness” in sound. Several other similarly shaped Grancino viola d’amores survive, with varying numbers of strings and in different sizes. In fact, his instruments were distinguished in part by the lack of standardization in their construction. Of the surviving pieces, one has four strings, two have five, and the Met’s example, in particular, underwent a reconstruction to restore it with its original six strings. 3. A bell that rings in ceremony and spectacleA Japanese densho circa 1856 can be found among the Met’s collection. This leaded bronze ceremonial bell was used originally as a call to Buddhist prayer. With its depictions of dragon heads, flames, and a delicate chrysanthemum denoting the striking surface, this densho displays symbols common to many East Asian cultures. Japanese kabuki theater still sometimes incorporates the sound of a densho into performances. 4. A magical fluteAn elegant little transverse (side-blown) flute created by Claude Laurent in 1813 also adorns the Met’s musical collections. Fashioned of glass and brass in Paris, the flute incorporates its designer’s skill as a watchmaker into its construction. Laurent employed various kinds of glass, as well as lead crystal, to create flutes in multiple colors. Made from delicate white crystal, the Met’s flute features four brass keys. With his other flutes, Laurent followed Theobald Boehm, the early 19th-century inventor and musician responsible for the flute as we know it today, to fashion flutes with greater complexity in their keying arrangements. After Laurent died, interest in his type of crystal flute fell away. Even so, his construction of keys affixed to “pillars” on the instrument remains a standard component of flute design today. 5. A guitar beautiful in sound and formAn intricately ornamented guitar constructed toward the close of the 17th century offers visitors to the Met a look at the care an instrument-maker from the past could lavish on one of his creations, from an aesthetic, as well as a functional, point of view. Scholars attribute this guitar to Jean-Baptiste Voboam, who was one of an entire family dynasty of stringed instrument-makers working at a time when France was just beginning to come into its own as a source of fine guitar-making. Whoever its maker may have been, its use of tortoiseshell, ivory, ebony, mother-of-pearl, and spruce make this guitar a particular pleasure to view. 6. A drum with many beatsA double-headed tánggǔ drum produced in 19th-century China during the Qing dynasty also adorns the Met’s collections. This lacquered example—fashioned from teak, brass, and oxhide—comes from Shanghai. Depending on where on the surface the player strikes the oxhide, the barrel of the drum will produce a rich variation of musical volume and tone.

This type of drum typically found its way into both Buddhist ceremonial activities and the performing arts. Today’s Chinese orchestras often make use of a modern-day form of the tánggǔ. Learning to play a musical instrument can open up many exciting new adventures for a child and their family. To further encourage your child’s interest and enhance their learning, why not visit one of the following museums on your next family vacation? Music-focused museums can help your child appreciate their chosen instrument even more and see its place in the rich tapestry of humanity’s musical heritage. 1. The Met in New York shows how art sounds. Image by Moody Man | Flickr Image by Moody Man | Flickr The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City needs no introduction as an art museum, but it is often overlooked as a rich source for learning the history of musical instruments. The Met’s world-renowned collections include some 5,000 instruments from all over the world, with some dating back more than 2,000 years. The focus is on demonstrating how musical instruments have developed across cultures and throughout the centuries. “The Art of Music Through Time,” housed in Gallery 684, is filled with objects, audio and video commentary, and related artworks that provide a multisensory illustration of the power of music. Meanwhile, the André Mertens Galleries for Musical Instruments house hundreds of instruments from Western and non-Western traditions. These include a group of Stradivari violins and the oldest known piano still in existence. There’s also “Fanfare,” an exhibit that centers on 75 specific brass instruments—“brass” interpreted as any tubular instrument played via a mouthpiece—that range from ancient hunting horns to a plastic vuvuzela manufactured to commemorate the World Cup of 2014. In addition, the Organ Loft houses the Thomas Appleton Organ, constructed in the first third of the 19th century and one of the earliest American working pipe organs. 2. An acclaimed musical instrument museum in the desert.The widely praised Musical Instrument Museum (MIM) in Phoenix, Arizona, is home to more than 13,000 instruments—about half of them on display at any given time—from almost every country in the world. The museum works with the goal of acquiring instruments of every time and place, with a special emphasis on folk and tribal instruments. One entire gallery is dedicated to modern popular music. In this Artist Gallery, the objects on display honor artists from Pablo Casals to John Lennon, and Elvis Presley to Taylor Swift. Many of the museum’s installations feature audio or video recordings of iconic performances, while the Experience Gallery gives families a chance to actually play some of the world’s representative instruments. In addition, the MIM hosts regular performances that highlight a range of musicians and styles from around the world. 3. A cultural treasure being rebuilt in the Great Plains.The National Music Museum in tiny Vermillion, South Dakota, has received accolades from the New York Times as one of the most important music museums in the world. It curates some 15,000 instruments, representing every part of the world and almost all of its cultures and time periods. The museum’s collections include a viola made by the renowned Andrea Guarneri in the mid-17th century, and one of the earliest grand pianos ever constructed. Its walls also house a wide range of fascinating musical exotica, including stringed instruments crafted to resemble peacocks and harmonicas shaped like goldfish. High-tech exhibits rely on iPod Touch technology to play performance recordings of the instruments on display. Currently undergoing a major reconstruction and expansion, the National Music Museum is set to reopen in 2021. It continues a lively current dialogue with its fans on Facebook, often offering video clips and pictures of some of the pieces in its collection. 4. See Mozart’s piano in Prague.The Czech Republic loves and honors music and musicians. In the 1780s, for example, the capital city of Prague opened its arms to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and he conducted the world premiere of his opera Don Giovanni in its Estates Theatre. So it makes sense that Prague is the site of one of the world’s finest museums of musical instruments. Located in a former historic church in the Lesser Town near the Vltava River, the Czech Museum of Music is a constituent part of the county’s National Museum. Within its walls are displayed some 400 musical instruments, each with extraordinary artistic and cultural value. An architecturally stunning atrium provides a lovely location for a journey through “Man-Instrument-Music,” the museum’s permanent exhibit, which delves into the many connections between people and instruments over time. On view in the exhibits are a variety of stringed and wind instruments. A grand piano that Mozart once used is just one of the extraordinary objects on display. Museum goers enjoy a heightened experience as their journey through musical history is accompanied by musical recordings played alongside the instruments in the exhibits. The museum additionally hosts regular concerts and special exhibitions. 5. Brussels houses musical treasures in an architectural wonder.The Musical Instruments Museum in Brussels, Belgium, is another among the premier museums of its kind in the world. Housed in a restored, half-Neoclassical and half-Art Nouveau building complex, it houses a collection of more than 1,000 instruments ranging over four audio- and video-enhanced galleries that cover a variety of historical and contemporary periods.

The Brussels museum is part of the Royal Museums of Art and History, which makes its Carmentis online catalog, listing each of its instruments, publicly accessible. One fun feature of its website, at www.mim.be/en, is the Instrument of the Month. The Musical Instruments Museum also encompasses a concert hall and a rooftop restaurant terrace with stunning views of Brussels. The universality of music as an art form—and as a cultural treasure—has become a cliche. However, as music teachers know, that cliche represents an important truth about the way in which music can expand horizons, facilitate understanding, and contribute to a broader appreciation of the heritages of all the people in the world. Children who learn that there are others much like themselves who make music, dance, and sing together just as they do, can be a powerful motivator for them to learn more about other cultures. And when they participate in positive programs that introduce them to cultures other than their own, they learn to become more tolerant and accepting of other human beings. In addition, participation in multicultural musical activities exposes children to a wider variety of sounds, intonations, and rhythms than they would ordinarily experience at home. Educators point out that the process of teaching children music from a rich variety of cultures should begin in early childhood with an emphasis on broad participation. And any good early childhood music program will typically incorporate rhythmic movement activities and opportunities to develop social skills. Studies validate multicultural music experiences.Research has shown that when children hear music from other cultures, they develop the ability to perceive fine distinctions among sounds. This is just the type of experience that helps them to acquire and build on vital early language skills. They also learn the art of listening and increasing their ability to concentrate. Experts assure anxious parents that hearing music in multiple languages—just as in the case of learning a second language—actually helps young children to improve their primary language skills. World Music Day honors many traditions.In fact, there is an entire day dedicated to the celebration of listening to, performing, and enjoying music from all over the world. World Music Day, which is observed in a multitude of ways in numerous countries, occurs on June 21 of each year. The observance began in France, as Fête de la Musique, in the early 1980s. Since then, it has served as a means of promoting free access to music for everyone in some 700 cities worldwide, and it is supported by organizations such as Musicians Without Borders. A treasure trove of recorded music.Teachers and parents who want to focus on offering a multicultural palette of musical experiences can begin with one of the many well-reviewed recordings for children. These include the series published by Putumayo, which provides high-quality CDs of representative musical compositions from a wide range of cultures for children of all ages. Putumayo’s children’s catalog, which is available online, includes the classroom favorite and Parents’ Choice award-winner World Playground. The label’s other selections include Kids’ African Party, which also offers an aid to learning with a list of instruments and musical genres that are distinctly African. Other Putumayo titles include Cuban Playground, Italian Playground, and other “Playground” CDs featuring musical styles from New Orleans, Brazil, France, and the Caribbean. The albums are joined by several “Dreamland” collections, featuring multicultural songs suitable for quiet family times. A classic American performer interprets the music of the world.Ella Jenkins is a performer beloved by generations of parents and children. Jenkins, an African-American singer and actress, has worked since the 1950s to deliver definitive renditions of a wide range of folk songs for audiences of children. Her albums are available on the Smithsonian Folkways label. Jenkins’ classic Smithsonian Folkways albums include Multi-Cultural Children’s Songs and More Multicultural Children’s Songs. Children can enjoy songs from these albums that teach common greetings in many languages, including Swahili. Other tracks include renditions of beloved songs depicting the cultures of Israel, China, Australia, Germany, and many other nations. Smithsonian also publishes Jenkins’ early albums Call and Response: Rhythmic Group Singing, which introduces listeners to West African music, and Adventures in Rhythm, which teaches awareness of rhythmic concepts in music from the very basic to the more complex. A bilingual educator offers multiple ways to learn music.José-Luis Orozco is another musical artist with an international catalog that spans decades. A teacher with a master’s degree in education, Orozco has made a career of sharing the joys of music in Spanish and English with children and their families. He performs throughout the Americas to promote the value of bilingualism and multicultural understanding. Orozco’s albums include Caramba Kids, De Colores, Esta es mi tierra/This Land Is Your Land, and numerous others. His website also offers educational kits that can enhance classroom music and cultural programming. Putting traditional American classics in a global frame.Another Smithsonian Folkways artist, Elizabeth Mitchell, offers recordings anchored in her early work as a teacher of young children in New York City. Her classes consisted of children who spoke a wide range of languages. Mitchell discovered that music could serve as a bridge among cultures. She has since gone on to immerse herself in the American and world folk music traditions. Her highly accessible albums include You Are My Little Bird, which features interpretations of American Appalachian and other folk melodies appropriate for all ages.

|

Photo used under Creative Commons from Marina K Caprara

RSS Feed

RSS Feed