|

The study of an instrument is a long-term commitment. Students will need to feel comfortable with their choice and dedicated to getting the most out of their studies. With hard work, focus, and diligence, however, learning to play an instrument can be a way to enrich a child’s life well into adulthood. The following seven tips can help parents, educators, and children identify the instrument that will be the best and most enjoyable fit. 1. Consider the child's age and development.First, consider the child’s age. For particularly young children, consider the physical and developmental demands of each instrument. Children of this age may not have the physical strength, dexterity, or muscle fluency to manage certain instruments. 2. Consider the piano and the violin, particularly for younger children.  Expert teachers typically recommend the violin and the piano for children under 6 years of age. Both of these instruments serve as excellent building blocks for learning music theory and practice. They also assist with learning to play additional instruments. The Suzuki Violin Method is one of the teaching practices that focuses specifically on the qualities of the violin as a young beginner’s instrument. Learning violin is made easier for younger children because the instrument can be fashioned in very small sizes. This makes it simpler and more intuitive for a child this age to manage fluidly and naturally. The violin is also an excellent choice of instrument for teaching young music students to play in tune. Another advantage is that the act of bowing provides a kinetic manner through which students can learn the concept of musical phrasing. And, because the violin has no keys or frets, a young player can concentrate completely on the sounds he or she is creating. The piano offers its own plusses as a first instrument. A child learning to play the piano picks up foundational skills of musicianship by becoming proficient in harmony and melody at one and the same time. Piano students gain experiential knowledge that will help them to better understand music theory. 3. Consider the child’s physical abilities and limitations.An instrument’s design and its fit with a child’s physicality is also an important consideration. If a child’s hands are relatively small, for example, he or she may not have the finger span to become an accomplished pianist or a player of a larger stringed instrument. For woodwinds and brass instruments, make sure that the embouchure—the place where the child places his or her mouth to produce sound—is a good fit. Keep in mind that some students take time to learn the best way to address this. The oboe has a double read mouthpiece and the French horn has a slender tube mouthpiece. As a result, these instruments present particular challenges regarding their fit against a player’s mouth. For children who need orthodontic help, it can be better to select a stringed or percussion instrument. This is because blowing through any sort of embouchure may be uncomfortable or even painful. 4. Consider which instruments the child enjoys listening to.Sound is an important quality as well. A child should enjoy the sound her instrument makes. Otherwise, he or she may be reluctant to continue practicing and playing it. Experts point out that it is unrealistic to believe that, over time, a child will come to like the sound of an instrument he or she dislikes. Such a child may, instead, neglect lessons and resent practicing. This is particularly important for parents to remember, because band directors sometimes encourage children to take on specific, less-popular instruments simply because one is needed in the ensemble. 5. Consider the child's temperament.A child’s personality is another good indicator of the best instrument to select. For example, an outgoing child who enjoys being the center of attention will likely gravitate to an instrument that offers greater potential for front-of-the-band performance and solos. These instruments include the flute, saxophone, and trumpet. All are made to carry a central melodic line, rather than to play supporting roles. 6. Consider the social implications of the selected instrument.One factor sometimes swept aside by adults can have a big impact on children. This factor is the social image of an instrument, and what that says, by implication, to peers about a child’s own image and personality. Many children gravitate toward the instrument they perceive as having the most status among their peers. Unfortunately, that instrument may not be the best fit. Adults should encourage each child to take a fresh look at the instrument that actually seems best for him or her. 7. Consider your budget as well as any maintenance commitments.Practical issues of cost and maintenance will also be on most parents’ lists when choosing an instrument. Take some time to go over a realistic timetable of maintenance with a child’s music teacher. A piano, for example, is one of the most expensive instruments, and needs to be tuned twice annually by a professional.

Remember that many music vendors offer monthly payment programs. A trial rental may also be a good option until a child is certain that he or she really likes an instrument. Some schools will facilitate free long-term loans of instruments for their band members. It may also be worthwhile to explore options provided by nonprofit groups. For example, Hungry for Music supplies children in financial need with donated and carefully refurbished instruments. A 2016 piece in The Atlantic echoed numerous other recent articles noting that increasing focus on academic standards and testing in schools has led to a declining focus on character building and empathy. While parents and teachers are becoming more aware and concerned about this problem, music offers many solutions. Here are seven ways music education can promote social harmony: 1. Developing compassionate citizens.Renowned music educator Dr. Shinichi Suzuki, who originated the Suzuki method, understood that learning to play a musical instrument could be a significant part of learning to develop into a caring human being and a good citizen. In fact, many music teachers view the Suzuki method as being in a class by itself for this very reason. Experienced teachers also note that the same skills acquired when children study music lead to the development of positive character traits such as tolerance, respect, and a sense of perspective. Working together to study and perform a piece of music fosters a sense of common purpose and encourages collaboration with other people who come from a variety of backgrounds and possess a range of viewpoints. 2. Getting people in touch with their emotions.In their book Music Matters: A Philosophy of Music Education, published by Oxford University Press, David Elliott and Marissa Silvermann discuss the emotional component in music. This is a perennial topic in any discussion of music, going back to the days of the ancient Greeks. Both Plato and Aristotle commented on the ability of music to evoke either positive or negative emotions in listeners. Neurologists and psychologists focused on the power of music agree. In fact, sophisticated new research studies show how musical notes and chords can produce corresponding emotional states in listeners. 3. Counteracting bullying.In fact, a 2015 article in Psychology Today magazine even suggests some music is a possible antidote to extreme antisocial behaviors such as bullying and bigotry. The article points out that learning to play a musical instrument beyond the level of bare technical proficiency draws on a host of emotional skills and sensitivities. In order to produce the most pleasing sequences of sounds and reach the hearts of audience members, a player needs a certain level of emotional maturity and expressiveness. A range of talented musicians have opined that music can deepen and broaden an individual’s perspective. As a result, he or she can grow beyond early prejudices and begin to view other people with greater comprehension and appreciation. For example, the late jazz musician Paul Horn was once quoted as saying that music is an extremely useful way to bring people together in greater peace and mutual understanding, easing the burden of communicating across personalities and cultures. Numerous other musicians have specifically noted music’s power to overcome even the strongest racial and cultural prejudices. 4. Reducing violence.A group made up of musicians, producers, and others based at the University of California, Los Angeles created a collective performance space for the expression of a wide variety of world music instruments and genres. They called their collective Westwood Village Entertainment Group. It has worked to facilitate a welcoming environment for a diverse group of musicians, performers, and audiences. The idea emerged out of one young ethnomusicologist’s experiences growing up in a crime-filled neighborhood in New Jersey. The young man found escape through learning to play African drums. Now, because of WVEG, he and his fellow musicians hope to foster a sense of community and welcome. 5. Reminding listeners of relevant events or eras.The canon of popular music is filled with deeply moving, inspirational pieces that seek to heal the rifts and prejudicial attitudes that arise between people. Examples include Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On?” as well as Curtis Mayfield’s “We Got to Have Peace” and the classic hymn of the Civil Rights era, “We Shall Overcome.” 6. Reducing bias and promoting empathy.One study, published in Psychology of Music, centered on a social experiment with elementary school children in Portugal. Their community is composed of lighter-skinned people descended from families with long histories in the European country as well as darker-skinned people whose heritage lies in the African island nation of Cape Verde. Over a period of several months, the researchers introduced one group of young students to songs from Cape Verde in addition to their regular lessons in European Portuguese music. A control group did not receive exposure to the Cape Verdean songs. Before the study, all of the children surveyed displayed a moderate amount of bias against darker-skinned individuals. By the conclusion of the study, however, the children who had been exposed to the music of Cape Verde demonstrated significantly lower levels of such prejudice. The control group showed no change in their negative attitudes. The researchers in this study theorized that, for the children involved, learning to like the music of Cape Verde translated over into learning to like the other children whose families came from Cape Verde. This aligns with a principle identified in psychological research. The idea is that a feeling of similarity or having common interests with another person tends to increase empathy for that person. The researchers further theorized that songs may be particularly valuable tools for fostering feelings of commonality and similarity, and thus of empathy. 7. Strengthening interpersonal relationships.A 2015 article in Music Educators Journal makes a similar point. Its authors posit that the collaborative experience of making music with others involves activities such as synchronization, group problem-solving, imitation, and call-and-response.

All these activities tend to have a positive influence on interpersonal relationships and on individuals’ abilities to work successfully in groups, and thus, on the development of empathy. According to experts, the themes of music are the themes of human life itself. Therefore, learning to make music makes us more human. The brass family of musical instruments takes its name from the material with which they are made, and their booming, brassy sound makes a big impact. The brass instruments that most young students will encounter are the French horn, tuba, trombone, and trumpet. They might also meet the cornet, which is very similar to the trumpet, and the sousaphone, closest in style to the tuba. The euphonium and the baritone are less well-known—their size and range fall somewhere between the trumpet and the tuba. Buzzing mouthpieces, valves, and pipesMusicians play brass instruments, as they do members of the woodwind family, by pushing their breath into the instrument. But, unlike the woodwinds, it is not a vibrating reed, but a metal mouthpiece shaped like a cup, that amplifies the sound and drives it forward as the player’s lips buzz against it. Today’s brass instruments consist of a long stretch of tubing or piping that flares out toward the end like a bell. In order to allow for better and smoother handling and playing, the instruments’ pipes are configured into twists, curves, and curlicues of various types. Attached to the pipes are a variety of valves that allow the player to open or close a range of apertures along the pipe’s length. When a player presses down on various combinations of valves, he or she can vary the sound, loudness, and pitch. The clear, strong sound of the trumpetThe trumpet and the cornet are the smallest and highest-pitched members of the brass family. The differences between the two are miniscule, and their sounds are almost indistinguishable, although the trumpet’s shape is slightly longer and slimmer. Beginning players typically find that neither is an improvement on the other. The trumpet is easy to maintain and to store, with only two body pieces to take apart between one band practice and the next. The instrument’s valves and slides need occasional oiling. The earliest prototype of the trumpet we know today appeared in approximately 1,500 BC. Early artisans began to decorate the horns they fashioned from animal tusks, and eventually from ceramics and metal. But the trumpet remained largely a one-note hunting, ceremonial, and wartime accessory until the latter part of the Middle Ages. It was then that musicians began to realize its artistic possibilities. Baroque composers began to incorporate the trumpet into their compositions, impressed with its clear, ringing tone. By the close of the 1700s, Viennese musician Anton Weidinger had added keys to the instrument, giving it the capacity to produce a complete chromatic scale in all registers. The invention of valves replaced the keyed system, and by the second decade of the 1800s, the first working brass instrument valve ushered the trumpet into the modern orchestral age. Makers of early musical recordings were so taken with the strong, bold sound of the trumpet that they featured it often, and superstar players such as Louis Armstrong made it an indelible part of the American musical experience. Learning to slide with the tromboneThe trombone’s long slide piece increases the length of its tubing and changes its pitch, making the slide analogous to the valves found on other instruments. Like the trumpet, it ends in a bell-shaped piece, but has a larger mouthpiece than the trumpet. The trombone is relatively more challenging to play and to care for than other brass instruments. It’s important to take particular care of the slide and treat it gently—if it is damaged, the instrument becomes unplayable. The trombone’s two-piece structure makes it easy to assemble and disassemble, and, like the trumpet, it simply requires occasional oiling and greasing. Students who have good pitch will be able to know exactly how far to extend the length of the slide to produce a desired tone. Students who are unsure of pitch may have more difficulty in controlling the trombone’s pitch. The trombone arose as a byproduct of the development of the trumpet in the 1400s. Until hundreds of years after its invention, musicians and composers in the English-speaking world called it the “sackbut.” From cor de chasse to French hornThe model for the French horn was based on ancient horns used for hunting. Its name is a bit of a misnomer, since most of the major developments in the instrument took place in Germany. Like its relatives, it was developed during the late-medieval period, when musicians’ experimentation created a variety of new horn types. Seventeenth-century alterations in horn formations produced a model with a larger flared bell, the first recognizably “French horn” type of instrument. This model was originally called the “cor de chasse” and then the “French horn” in English. Complete beginners are not usually capable of attaining great proficiency in playing the French horn, and so should proceed with caution before settling on it as a band instrument. But for a student with an excellent grasp of pitch and solid prior musical training, it can be a good choice. Like other brass instruments, the French horn is comparatively simple to store and to care for. The big and beautiful tubaThe tuba, the brass family’s largest instrument, is also its deepest. It can play both accompaniment and melody, adding surprisingly nuanced and beautiful tones.

Students can obtain tubas of various sizes; it’s important for each musician to identify the size that’s right for them. Younger players who struggle with the full-sized tuba may find that the baritone is a more manageable instrument, at least at first. The tuba’s care is similar to that of other brass instruments, and it consists of at most three pieces. Unlike its cousins, the tuba’s origins lie not in ancient or medieval times. Drawing on previous valved band instruments, two Berlin-based musicians filed a patent for the tuba in 1835. Johann Gottfried Moritz and Wilhelm Wieprecht provided their new instrument, set in the key of F, with five valves. Later variations include the Wagner tubas, small-bore models created specifically to fit composer Richard Wagner’s requirements in his large-scale opera The Ring of the Nibelung. According to the National Association for Music Education (NAfME), early learning music programs should include numerous opportunities for exploration through listening, singing, dancing, and other kinds of movement. In addition, teachers should provide the opportunity for kids to actually play musical instruments. Both learning how to play an instrument and learning about music assist young children in developing critical thinking skills and empathy, and promote positive socialization. By making music together, young children also get the chance to experience a wide range of cultures, learn new words, and develop vital senses involving body and spatial awareness, as well as fine and gross motor skills. Every child has the potential to make music and to develop a lifelong appreciation for it. The key is to provide a rich range of developmentally appropriate musical experiences that allow for participation. In a general early childhood classroom, teachers should emphasize fostering a wide and deep appreciation for music, rather than on training children to attain performance-level proficiency. Here are a few insights, gathered from the NAfME’s website and a range of other parent and teacher resources, about the specific instruments, practices, and activities that can make sharing music with young children especially vibrant and meaningful: 1. Select music literature for the classroom with a focus on quality.The selection of music literature in an early education music classroom should acquaint children with high quality works of classic status or perennial value. These can include traditional folk tunes, the works of the classical music repertoire, and world music produced by a range of different cultures over time. 2. Look for age-appropriateness.Professional educators note that it is vitally important to calibrate the types of materials and activities in an early childhood music classroom to children’s developmental age. Children become bored and will not engage if the material is too complicated or goes over their head. 3. Set up for fun.Teachers can have a container of rhythm instruments, such as maracas, tambourines, shaker eggs, handbells, and other percussion instruments ready for impromptu group music-making. They can also stock a basket with accessories such as scarves, feathers, ribbons, and other things that kids will enjoy swirling, twirling, and dancing with. If the classroom can accommodate it, a microphone is a great way to instill self-confidence in young performers who love to sing. And a quiet listening corner filled with choices of classical, jazz, and world music recordings can offer young children the opportunity to further expand and refine their musical tastes on a self-directed basis. 4. Add some real instruments.Teachers, music educators, and parents tend to recommend certain types of instruments as the most appropriate for young children to become acquainted with at home or in the classroom. These include bells, the xylophone, drums, the piano, and the guitar. 5. Sound the bells.A set of color-coded desk bells can be an easy and fun way for young children to learn about the variety of notes and tones. Their clear, simple tones are easy to distinguish from one another. Bells are easy to play—there are no keys, strings, or anything else to manipulate. An additional advantage is that a typical set of desk bells is tuned to the C-Major scale. Because young children typically understand color long before they can connect the name of a note to a sound or tone, it’s much easier to teach them that the blue bell sounds a certain note than it is to describe it as the “C” bell. In addition, bells are far easier to master at a young age than most other instruments, thanks to the fact that a set of desk bells typically consists of no more than eight notes. 6. Beat the drums.Drums are another favorite with young children, with good reason—they’re simple and easy to understand and to use, and offer the immediate reward of sound. Bongo drums are a good choice for young children’s drums, particularly in the classroom, because of their smaller and more manageable size. Although they don’t help with the development of pitch, playing drums builds coordination, and the associated sounds and movements help kids acquire a sense of rhythm. Another advantage is the limited number of sounds a drum can make, a factor that introduces a welcome predictability and familiarity for the youngest students. 7. Pound the xylophone.A color-coded xylophone is a great way to give a young child an appreciation for notes and pitch. Its clear pitch and lengthy, sustained sounds help with pitch recognition. Some xylophones provide a way to remove and rearrange their components, giving a teacher or parent the flexibility to limit a child to only a few notes at a time for instructional purposes. 8. Strum the guitar.Parents and teachers can purchase small, relatively inexpensive guitars designed especially for young hands. A guitar has the advantage of being portable; a young child can wear it throughout much of the day at home or in the classroom, which allows him or her to make up a song or sing a tune whenever the feeling strikes. Thanks to the many guitar-playing icons of popular culture, the instrument can also seem “cool” and “grown-up” to a young child. In addition, there’s a wealth of resources available for teaching and making music with this popular instrument. There are a few potential drawbacks to the guitar, however. It requires a bit more coordination, time, and practice to produce something that sounds like a melody. The notes on a guitar can also be confusing for young children, as there are multiple ways to produce the same note—for example, there are several middle C’s. In contrast, on the piano, there’s only one. 9. Learn the magic of the piano.A number of music educators recommend the piano as an excellent choice for a first instrument, even for preschoolers. Though more complex than the drums, the piano offers a distinct and organic way of teaching relationships among notes, chords, and types of musical compositions.

The piano also offers an immediate reward, in that there is a one-to-one correspondence between a child’s actions (hitting a key) and the emergence of sound. The instrument can also teach fine motor skills and help a child develop an appreciation for subtle distinctions in pitch. The universality of music as an art form—and as a cultural treasure—has become a cliche. However, as music teachers know, that cliche represents an important truth about the way in which music can expand horizons, facilitate understanding, and contribute to a broader appreciation of the heritages of all the people in the world. Children who learn that there are others much like themselves who make music, dance, and sing together just as they do, can be a powerful motivator for them to learn more about other cultures. And when they participate in positive programs that introduce them to cultures other than their own, they learn to become more tolerant and accepting of other human beings. In addition, participation in multicultural musical activities exposes children to a wider variety of sounds, intonations, and rhythms than they would ordinarily experience at home. Educators point out that the process of teaching children music from a rich variety of cultures should begin in early childhood with an emphasis on broad participation. And any good early childhood music program will typically incorporate rhythmic movement activities and opportunities to develop social skills. Studies validate multicultural music experiences.Research has shown that when children hear music from other cultures, they develop the ability to perceive fine distinctions among sounds. This is just the type of experience that helps them to acquire and build on vital early language skills. They also learn the art of listening and increasing their ability to concentrate. Experts assure anxious parents that hearing music in multiple languages—just as in the case of learning a second language—actually helps young children to improve their primary language skills. World Music Day honors many traditions.In fact, there is an entire day dedicated to the celebration of listening to, performing, and enjoying music from all over the world. World Music Day, which is observed in a multitude of ways in numerous countries, occurs on June 21 of each year. The observance began in France, as Fête de la Musique, in the early 1980s. Since then, it has served as a means of promoting free access to music for everyone in some 700 cities worldwide, and it is supported by organizations such as Musicians Without Borders. A treasure trove of recorded music.Teachers and parents who want to focus on offering a multicultural palette of musical experiences can begin with one of the many well-reviewed recordings for children. These include the series published by Putumayo, which provides high-quality CDs of representative musical compositions from a wide range of cultures for children of all ages. Putumayo’s children’s catalog, which is available online, includes the classroom favorite and Parents’ Choice award-winner World Playground. The label’s other selections include Kids’ African Party, which also offers an aid to learning with a list of instruments and musical genres that are distinctly African. Other Putumayo titles include Cuban Playground, Italian Playground, and other “Playground” CDs featuring musical styles from New Orleans, Brazil, France, and the Caribbean. The albums are joined by several “Dreamland” collections, featuring multicultural songs suitable for quiet family times. A classic American performer interprets the music of the world.Ella Jenkins is a performer beloved by generations of parents and children. Jenkins, an African-American singer and actress, has worked since the 1950s to deliver definitive renditions of a wide range of folk songs for audiences of children. Her albums are available on the Smithsonian Folkways label. Jenkins’ classic Smithsonian Folkways albums include Multi-Cultural Children’s Songs and More Multicultural Children’s Songs. Children can enjoy songs from these albums that teach common greetings in many languages, including Swahili. Other tracks include renditions of beloved songs depicting the cultures of Israel, China, Australia, Germany, and many other nations. Smithsonian also publishes Jenkins’ early albums Call and Response: Rhythmic Group Singing, which introduces listeners to West African music, and Adventures in Rhythm, which teaches awareness of rhythmic concepts in music from the very basic to the more complex. A bilingual educator offers multiple ways to learn music.José-Luis Orozco is another musical artist with an international catalog that spans decades. A teacher with a master’s degree in education, Orozco has made a career of sharing the joys of music in Spanish and English with children and their families. He performs throughout the Americas to promote the value of bilingualism and multicultural understanding. Orozco’s albums include Caramba Kids, De Colores, Esta es mi tierra/This Land Is Your Land, and numerous others. His website also offers educational kits that can enhance classroom music and cultural programming. Putting traditional American classics in a global frame.Another Smithsonian Folkways artist, Elizabeth Mitchell, offers recordings anchored in her early work as a teacher of young children in New York City. Her classes consisted of children who spoke a wide range of languages. Mitchell discovered that music could serve as a bridge among cultures. She has since gone on to immerse herself in the American and world folk music traditions. Her highly accessible albums include You Are My Little Bird, which features interpretations of American Appalachian and other folk melodies appropriate for all ages.

At the center of today’s symphony orchestra is the string section. The family group of stringed instruments includes the violin, the viola, the cello, and the double bass. This group’s defining features are strings, frets, and bows. The word “violin” is actually a diminutive term for “viola,” meaning that the instrument descends from the older viol family. The original Italian term for the latter instrument is “viola da braccio,” or “viol for the arm.” Held against the musician’s shoulder, this is the type of viol from which the modern viola developed. The following are some interesting facts about the always lyrical, expressive, and resonant violin: 1. It came into being during the Middle Ages.Some experts believe that the introduction of the violin into Europe began with the stringed instruments of Arab-ruled Spain in the early Middle Ages. The instruments of the cultures of the Iberian Peninsula at the time included the rabab and its descendant, the rebec. The latter had three strings, was shaped like a pear, and was often played with its base resting against a seated player’s thigh. Musicologists consider Central Asia the most likely ultimate origin for the bowed chordophone instruments that began to proliferate throughout Europe and Western Asia by the early Middle Ages. The Polish fiddle may be one of the direct progenitors of the violin. In addition to the rebec, other medieval instruments that led to the development of the violin included the lira da braccio and the fiddle. The shape of the lira da braccio, in particular, with its arching body and low-relief ribs, prefigured today’s familiar violin. The lira da braccio’s shallowness of body likely led to the addition of a sound post, a device particular to the violin and later to the viols. The sound post is a small, vertically positioned dividing wall that separates the instrument’s front and back in order to keep the pressures exerted on the strings from causing the belly arch to cave in. Musicologists point out that this sound post contributes to the richness of the violin’s lilting, singing tone, as it harmonizes the workings of the body and strings as a unit. By the end of the medieval period, a fiddle of a type that would be recognizable today appeared on the scene. 2. The Amati family refined the violin during the Renaissance.According to paintings of the time, violins with three strings were being played by at least the early 16th century. Lute-maker Andrea Amati of Cremona in Italy produced several violins with three strings at about this time. At about the middle of the 1500s, violins with top E-strings had appeared. It was then that the cello—or “violoncello”—and viola also branched out of the viol family. Bowed instruments developed further in tandem with the Renaissance, particularly in Italy, with the Amati family being the most famous violin-makers of the 16th and early 17th centuries. The Amatis’ great innovation was the development of the thinner, flatter, violin body that produced a particularly appealing sound in the soprano register. 3. Stradivari established impeccable standards.While the Amatis played a major role in standardizing the general size and proportions of the stringed instruments we know today, one of their apprentices, Antonio Stradivari, would carry forward and expand on their technical skills. By the late 1600s, Stradivari had created a wholesale alteration in violin proportions through elongating the instrument. His now-standard form for its bridge and general proportions has rendered it capable of producing sounds of extraordinary power and range. At one time, it was believed that Stradivari’s violins drew their range and depth of tone from the secret formula he used for their varnish. No one, then or now, has ever figured out that formula. Today’s music historians note that the distinct sound of Stradivari’s violins most likely derived from the quality of the vibration facilitated by thicker wooden top and rear plates, as well as from the configuration of miniscule pores in the wood. However, many experts additionally point out that the master’s varnish did indeed contribute to the overall quality of the sound. 4. Virtuosity became the goal for violinists in the 19th century.Into the 1800s, violin-makers continued to try new ways to construct the instrument and refine its proportions, angles, and arches. At this time, the repertoire for solo and accompanied violin began to require high levels of skill and dexterity, and violinists such as Niccolò Paganini became known for executing tremendously complex passages. Paganini, who cultivated the image of the composer-musician as a wild Romantic, amassed an enormous and devoted fan following in his day. Such virtuosity was further enhanced when Louis Spohr invented the chin rest sometime around 1820, thus enabling a player to more comfortably hold and manipulate the instrument. The addition of a shoulder rest additionally contributed to this ease of handling. 5. There are many modern-day virtuosos.A number of 20th- and 21st-century players have rivaled Paganini in skill and popularity. Among these are the child prodigy and older grandmaster Yehudi Menuhin, who died in 1999 at age 82. Menuhin’s technical proficiency dazzled audiences, and he became known for his championing of contemporary composers such Béla Bartók. Itzhak Perlman, born in 1945, remains one of the world’s finest living violinists, known for his focus on detail. While still in his teens, Perlman made his debut at Carnegie Hall. A Grammy Award winner for lifetime achievement, he has since played with jazz and klezmer groups, and performed music for motion pictures. In addition to his work as a conductor, he has also served as a teacher of gifted young musicians. 6.Today, the violin encompasses a mosaic of musical cultures.Like Perlman, today’s violinists perform not only classical music, but also an entire world of country, bluegrass, folk, rock, and world music. Throughout North Africa, Greece, the Arab world, and the southern part of India, the violin and viola continue to be very popular. The Roma have a long tradition of using the violin in communal music-making, as do the Jews through the tradition of klezmer. The violin remains widely used in American and European folk compositions as well.

The lilting, lyrical tones of the flute make it one of the most popular instruments for young musicians and one of the easiest to recognize in an orchestra. Experts recommend that you begin to teach the flute and other woodwinds when your child is old enough to have developed adequate lung capacity—typically by ages 7 or 8—and the dexterity to hold and manage an instrument correctly. The flute, which is also one of the oldest-known instruments, has a fascinating history, as it has developed over time: 1. Ancient OriginsThe flute, which is the first-known wind instrument, was used by Stone Age people. Flutes have been fashioned from animal bone, wood, metal, and other materials. The oldest-known example of a Western-style, end-vibrated flute dates back at least 35,000 years ago. Unearthed near the town of Ulm in Germany, the flute was made from the bone of a griffin vulture. Early flutes tended to be end-blown, played in the same vertical position as the recorder is today. Later evolutions resulted in the side-blown—or transverse—flute attaining the form we now know today. Ancient Sumerians and Egyptians used flutes fashioned from bamboo, eventually adding three and four finger holes that increased the number of individual notes they could play. Ancient Greek flutes were end-blown and had six finger holes. The Romans are known to have played transverse flutes, which may have been introduced to Western Europe by the Etruscans as early as the 4th century BCE. The ultimate source of the transverse flute was likely Asia, reintroduced to early medieval Western Europe via the Byzantine Empire. 2. Medieval and Renaissance Pipes, Fifes, and FlutesMedieval flutes, which were typically wooden, with six open finger holes and no keys, were often paired with a drum as the minstrels’ portable pipe-and-tabor set. The Renaissance witnessed the development of flutes, often made from boxwood, with two groupings of finger holes and a slimmer cylindrical bore. While this new design made the tone lighter and more airy and delicate, the sound from the lower register became more problematic. Military bands continued to use the smaller fife. 3. The Flute Replaces the RecorderThe transverse flute began to displace the recorder in the middle of the 17th century, and before another century had passed, it had moved into a place of popularity among a wide range of composers. During this period, changes in the flute’s size and shape conferred upon it a greater musical range. Its larger chromatic range made it capable of evoking a rich palette of moods, from the pastoral to the sprightly, to dramatic declarations of love and soaring flights of fantasy. In the Baroque period, French musical instrument makers—the Hotteterre family chief among them—introduced major changes. They included the creation of three joints for the instrument, increasing to four joints by the early 18th century. The Baroque flutes also featured a bore that tapered toward the foot end. The alterations permitted cross-fingering in order to play in various keys. They additionally made upper-register volume and tuning better. New sliding joints permitted the flute to be tuned in tandem with other instruments of an ensemble. The designation “flute” in compositions from the Baroque period typically continued to mean the recorder, with the transverse flute becoming commonly known as the “German” flute. 4. A Classical FlourishingBy the early 1800s, the flute had six keys and would soon add two more. These classical flutes, like their earlier Western European counterparts, were usually made of wood with a cone-shaped shaft and six keys. The flute as we know it today took its modern form at the time of the Classical period in music, the era of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. During this time, the flute became an integral part of the symphony orchestra. 5. Baroque and Classical Music for FluteIn 1681, Jean-Baptiste Lully became the first to write the transverse flute into an operatic orchestra. Over the Baroque and Classical periods, a number of composers created compositions showcasing the capabilities of the flute. Early 18th century composer Georg Philipp Telemann’s Twelve Fantasias for flute without bass presents flutists with passacaglias and fugues that demonstrate the many possibilities of the instrument, including the “false polyphony” resulting from rapid changes in tone and subject, with the high and low registers alternating. Mozart wrote his Flute Concerto in G major, No. 1, K. 313, which contains a liltingly expressive Adagio movement, encased by lively Allegro and Rondo movements. Beethoven composed numerous works for the flute. His Serenade in D major, Op. 41, is composed for flute accompanied by piano. The work is a series of six subsections, by turns serene and vivacious, introduced by an overture. Its Andante con variazioni e coda has earned praise from musicians as a supreme example of the composer’s art. 6. Boehm’s Lyrical RevolutionToday, flutists use the term “Western concert flute” to describe modern flutes descended from Western European models. This style of flute is also known as the “C” flute because it is usually tuned to that note on the scale, or as the “Boehm flute,” due to the influence of Theobald Boehm on its evolving design. The German-born Boehm, whose long career spanned most of the 19th century, was the greatest influencer of the way the modern flute looks and sounds. A flutist himself, as well as a goldsmith and artisan, Boehm produced a series of significant innovations in the design of the instrument beginning in 1810. Building on previous ideas of other instrument-makers, Boehm also adopted the idea of using larger tone holes, as well as the use of ring keys. In his iterations of the flute in the 1830s, Boehm provided tone holes organized to create the best possible acoustic values. He also linked the keys through a series of movable axles. He also adapted newly invented pin springs to his instrument and put felt pads on its key cups in order to impede the unnecessary escape of air. He altered the silhouette of the embouchure—the mouth hole—to make it rectangular, and constructed the instrument of German silver, for its superior acoustic qualities. By the close of the 1870s, Boehm was offering his “modern silver flute.” Over the course of his career, he produced a revolution in the way flutes were designed, constructed, and standardized. His basic flute design remains largely in use today. The Library of Congress holds a number of examples of Boehm’s flutes in its Dayton C. Miller collection. 7. Today’s Flute—An Ancient Instrument with a New VoiceModern flutes typically have 16 keyed openings, corresponding to an even-tempered octave. Many contemporary flutes possess a range of three octaves. Today’s flutes are typically made from blackwood or cocuswood, or from silver or a silver and nickel-silver alternative.

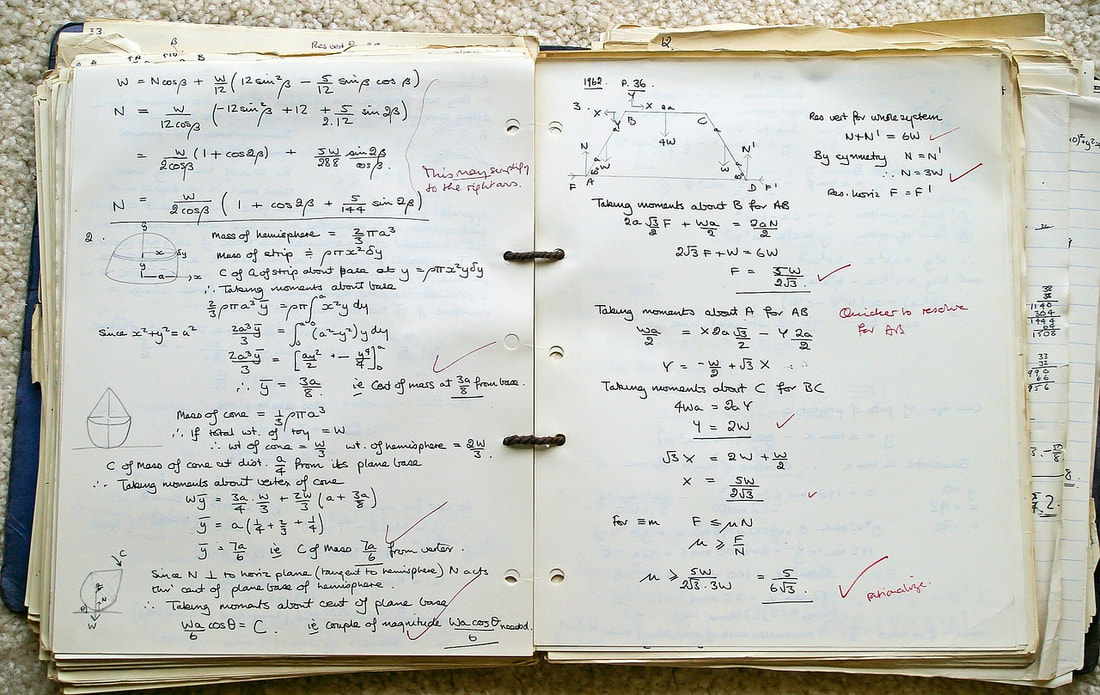

Current members of the flute family include the piccolo, the concert and bass (or contrabass) flute, all in the key of C, in increasingly lower registers and with different ranges. The lowest note on the hyperbass flute has a frequency of only about 16 hertz, considered lower than the lower limit of human hearing. Flutists today have a rich repertoire of solo and ensemble pieces to choose from, including works by earlier composers such as Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, a well as 20th century masters such as Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel, and many others. Pythagoras might have been speaking for numerous others when he said that he found music in the spacings between the planets and geometry in the sounds of strings. Plato wrote of harmonies in mathematics and how they parallel harmony in a just society. Confucius also found numerous eternal truths in the unfolding of pieces of music. These ancient philosophers grasped truths about the interconnectedness of music and mathematics that have become even more clear over the centuries. Here are only a few insights, based on the experiences of musicians and mathematicians, about this close relationship: 1. Activation of analogous skillsMusic students, when tested, tend to show more skill in mathematics than their non-musical peers. High levels of cognitive processing ability and executive function—which involves self-regulation and self-management in order to achieve a goal—are essential for success in both fields. Research also supports the notion that executive function, even more so than overall intelligence, has been shown to influence academic achievement. Learning math ties into the development of executive function by calling on a child to analyze, identify key concepts, and proceed through a series of logical steps. Likewise, learning to play a musical instrument enhances this capacity by, among other factors, drawing on the ability to calibrate motor movements in response to changes of time signature and key. 2. A beautiful symmetrySome mathematicians explain their field by focusing on how they work to extract the essential elements of any given thing and study the characteristics and interactions of those elements on an abstract plane. This type of learning can help students to understand music and can lead to a deeper engagement with the essential elements of a musical composition. Music can inspire students to learn more about mathematics through studying, for example, the properties and manifestations of sound. Innovative mathematics teachers have even brought opera singers into their classrooms to show students how the patterns of mathematics are part of the essence of music. 3. Simplicity within complexityEvery note a composer writes or a musician plays is involved in an intricate web of harmony, rhythm, and mathematical patterns. These patterns tend to be built around elements of symmetry. For example, just as the shapes of regular geometric figures remain the same when rotated, a musical tune can be transposed to another key in a composition such as a fugue. In a Mandelbrot set, a famous fractal, a smaller replica of the entire patterned set can always be found hidden at the core of any other image in the set. So, we might also say that a musical fractal occurs when one theme harmonizes with a slower version of itself. Johann Sebastian Bach, for example, showcased a talent for repeating his themes numerous times throughout a variety of permutations. 4. A composition made possible by mathIn fact, thanks to an extraordinary mathematical insight, Bach had the tools he needed to compose The Well-Tempered Clavier in 1722. The piece consists of a set of masterful preludes and fugues, one in each of the major and minor keys. But Bach could not have created this much-loved work without mathematics. In 1636, the French monk and mathematician Marin Mersenne successfully solved a difficult problem by deriving the twelfth root of the number 2, thus paving the way for the division of the octave into 12 equal semitones. Before this division and the associated method of equal temperament of musical instruments, pieces transposed into new keys often sounded uneven and unpleasing. But after Mersenne’s achievement, musicians were able to work with a 12-part octave, evenly spaced and divided into ratios. They could then write music in every key and transpose easily from one key to another. Bach’s The Well-Tempered Clavier was the first noteworthy example of this musical revolution. 5. How math determines pitchA discussion of pitch is only one way to demonstrate how math undergirds sound. Pitch is based on wave frequencies. All audible sounds are produced by changes in the air pressure of the pockets surrounding a sound wave. The frequency that hits the human ear translates into the perceived pitch. Each note possesses its own individual frequency. For an example of sound waves in action, think of a train whistle. Notice that the sound seems higher-pitched as the train approaches. But after the train goes by, the sound seems lower. As the train speeds toward the listener, the forward movement compresses the arriving air pockets against each other, thus pushing them forward more frequently. As a result, the sound seems higher-pitched. Then as the train recedes into the distance, the air pockets slow in their arrival to the ear, giving a lower pitch. We perceive the most pleasant-sounding chords when we combine notes with sound waves that reverberate in analogous patterns. The mathematical ratios of the intervals between notes give the means of calculating which note combinations produce harmony and which create discord. Frequency is measured in terms of hertz, and notes with higher pitch have a higher frequency. Middle C has a frequency of approximately 262 hertz. This means that, when middle C sounds on a piano, the sound waves that reach a listener’s ear consist of 262 pockets of higher air pressure striking against the ear every second. As a comparison, the E just above middle C sounds at approximately 329.63 hertz. Building an understanding of the physics and mathematics behind pitch also leads students to a fuller understanding of octaves, chords, and other musical elements. 6. Pairing music and math in the classroomWhen teaching music in the classroom, teachers can incorporate math in a multitude of ways. One is to ask older children to identify the parts of a musical pattern, then to restate the rule governing that pattern. They can go on to use their analysis of patterns to make predictions about the future direction of a composition. An exploration of time signatures and chords can also be the basis for lessons in how math and music work together.

Before younger children even learn the formal concepts of mathematics, they learn through experience about rhythm, repetition, and proportional relationships among musical concepts. They can clap out the syllables of their names, and then see if they can match the number of syllables in their own names to those in other students’ names. They can also echo their teacher, with voice or movement, as he or she calls out and varies notes, beats, and tempos. While numerous examples of lively, well-crafted contemporary music composed especially for children exist, educators and parents also have at their disposal a wide range of classical compositions that can foster a love of music. While not written specifically for young people, a variety of individual short works—and movements or pieces of longer works—from the classical repertoire have proven over the years to be as enticing for kids as they are for adults. These works include pieces by composers ranging from the towering, august Ludwig van Beethoven to popular 20th-century masters such as Aaron Copland. However, as diverse as these composers are, their compositions all feature strong melodic lines and rich tonality that can paint colorful stories across the canvas of a young listener’s mind. The following are a few suggestions for album collections, composers, and individual recordings that can enrich any child’s musical education: 1. Beethoven Lives UpstairsBeethoven Lives Upstairs is only one in the Classical Kids series of CDs and DVDs showcasing child-friendly pieces by great composers while emphasizing that these artists were also real-life human beings. This particular recording offers movements from Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 in C minor and Symphony No. 7 in A major, as well as pieces such as the composer’s Flute Serenade (Opus 23) and his popular piano composition Für Elise. The children’s media review organization Common Sense Media has praised this series as particularly suitable for kids ages 5 and up. The website’s review of the video version of Beethoven Lives Upstairs notes the vividness and accessibility with which it portrays the composer’s complex personality and depth of artistic expression. 2. Classical Wonderland - Classical Music for Children The album Classical Wonderland - Classical Music for Children, produced by Sony Music, offers a compilation of 11 recordings by various artists. Selections range from staples of the classical repertoire such as “The Flight of the Bumblebee” from Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera The Tale of Tsar Saltan to “The Swan,” one of the creatures portrayed in The Carnival of the Animals by Camille Saint-Saëns. The former piece depicts the antics of the prince when he disguises himself as a bee, while the latter paints a musical portrait of one of nature’s most graceful and elegant creatures. 3. My First Tchaikovsky AlbumAvailable online at the Met Opera Shop and in other venues, My First Tchaikovsky Album, from Naxos Records, offers kids some of their favorite melodies from the composer’s Nutcracker Suite and excerpts from The Sleeping Beauty, Swan Lake, and other works. A companion recording, My First Mozart Album, similarly extracts some of the most listenable tunes from that composer’s oeuvre. Naxos also offers kids My First Classical Album, featuring 21 Hungarian Dances by Johannes Brahms, Slavonic Dances by Antonín Dvořák, and Edvard Grieg’s Peer Gynt Suite. 4. Stories in MusicThe Stories in Music series, produced and sold by the music education company Maestro Classics, aims to make learning about great music even more fun through highlighting the entertaining tales its rhythms and beats tell. In albums of recorded music performed by the London Philharmonic Orchestra, Maestro Classics offers retellings of works with extra-high kid appeal, such as the rollicking magical hijinks of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice by Paul Dukas and Peter and the Wolf by Sergei Prokofiev. The genesis for these productions was a series of family classical concerts by the late Stephen Simon and his wife Bonnie Ward Simon. Mr. Simon was a well-known conductor who established, among other programs, an annual Handel festival at the Kennedy Center in Washington, DC. 5. Various Recordings for Play and RestThe youngest children often respond enthusiastically to classical compositions cause them to whirl, twirl, leap, and kick up their feet to a rapid beat. Music educators often suggest playing to toddlers’ need to move by using recordings of such extra-lively pieces as Brahms’ Hungarian Dances, Grieg’s “In the Hall of the Mountain King” from Peer Gynt, and pieces from Gioachino Rossini’s comic masterpiece The Barber of Seville.

The Barber of Seville offers even greater opportunities for nostalgic fun when parents share with their children the vintage 1950 Looney Tunes cartoon version. Called “The Rabbit of Seville,” the cartoon short features characters Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd in their now-classic bit. Other favorites to get the blood flowing for toddlers and their families include the “Hoe-Down” section from American composer Aaron Copland’s iconic ballet Rodeo, the energetic Russian Dance “Trepak” from Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker, and the whirligig rhythms of “Sabre Dance” from Aram Khachaturian’s ballet Gayane. “Sabre Dance” continues to enjoy broad recognition in popular culture as a common theme played in movies and television shows. Soothing music at bedtime can contribute to more restful sleep, as well as to an increased appreciation for music among children and their families. Music educators often recommend playing pieces such as Bach’s Suites for Solo Cello as lullabies. These collections of dance compositions—featuring gavottes, sarabands, minuets, and more—are among the most frequently performed works for the resonant instrument. Recordings such as Janos Starker’s Bach: Complete Suites for Solo Cello on the Mercury Living Presence label, for example, offer the slow, steady beats and flights of fancy that promote focused relaxation for parents and children alike. One of the most serenely lovely compositions ever created may be the Concerto for Flute and Harp by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Among suggested recordings of this dream-like piece is that featuring violinist Sir Yehudi Menuhin as conductor with the English Chamber Orchestra, available in various recorded editions.  Sergei Prokofiev | Image courtesy Wikipedia Sergei Prokofiev | Image courtesy Wikipedia In 1936, shortly after returning to the Soviet Union after living in Europe for 18 years, composer Sergei Prokofiev created one of the world’s most memorable and enduring musical pieces: Peter and the Wolf. Ever since, Peter and the Wolf has entertained children while educating them about the sounds of key orchestral instruments. Here are a few notes on Peter, the Wolf, their creator, and how this charming suite continues to be adapted to the needs of today’s music students: An instrument defines each characterIn Prokofiev’s story, every character has a signature instrument and tune that define individual personality. Music teachers can help children learn to identify the four families of instruments the composer used in the piece: strings, woodwinds, brass, and percussion. Peter is portrayed by a joyous leitmotiv from a string quartet. Peter’s animal friends are the bird, portrayed by a lilting trill on the flute; the duck, depicted through the waddling gait of the oboe; and the cat, who slinks through the story accompanied by the lower registers of the clarinet. The chugging of the bassoon portrays Peter’s stern and scolding grandfather, and the rolling kettledrums bring a group of hunters to life. A series of sinister blasts on three French horns conveys the menace of the wolf. A rollicking, melody-filled adventure storyIn Prokofiev’s original plot, Peter is a Communist Young Pioneer who lives in the forest at the home of his grandfather. When Peter is walking through the forest, he encounters his friend the bird flying through the trees, the duck swimming, and the cat stalking the birds. Peter’s grandfather comes out of the house to warn his grandson about the dangerous wolf that lurks in the forest, but Peter has no fear. The wolf eventually comes slinking past Peter’s cottage and devours the duck. So Peter avenges his friend and captures the wolf. He struggles with his captive but ends up tying him to a tree. The hunters appear, wanting to kill the wolf, but Peter persuades them to take the wild creature to the zoo, borne along in a celebratory parade. Peter and the Wolf earned quick success and is still beloved today by children, teachers, and parents. Prokofiev called on his memories of his own childhood for scenes and characters. A composer’s life in light and shadowsBorn in 1891 in what is now Ukraine, Sergei Prokofiev learned to play the piano as a child. When he grew older, his mother moved with him to St. Petersburg so that he might continue his studies with instruction at a higher level. He began his formal studies at the St. Petersburg Conservatory and became a skilled pianist, composer, and conductor. As a young man, Prokofiev became a dedicated traveler, intent on soaking up a variety of musical styles on visits throughout Europe and even to the United States. After the devastations of the Russian Revolution and the First World War, he settled in Paris, but he missed his homeland so much that he returned to the Soviet Union in 1936. He composed Peter and the Wolf for the Moscow Central Children’s Theatre that same year. As his career blossomed, Prokofiev studied artistic influences including Igor Stravinsky, ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev, and modernist artists such as Picasso. His oeuvre includes compositions for opera, ballet, and film. His symphonies and his concertos for piano, cello, and violin are notable among his works, as are his ballet Romeo and Juliet and his music for Sergei Eisenstein’s revered film Alexander Nevsky. As the Cold War began, Soviet authorities targeted the composer for exclusion from cultural life due to his supposed anti-traditionalist point of view. Because the United States feared Soviet aggression, Western audiences also cooled toward him. When he died in 1953—on the same day as dictator Joseph Stalin—few newspaper readers noticed. Disney works its magic on the storyThere have been numerous recordings of Peter and the Wolf since its debut. The most famous film version is undoubtedly the Walt Disney company’s animated short subject in full color. This film was presented as part of the 1946 feature-length compilation Make Mine Music, which included a variety of other cartoon shorts focused on making music education fun. In the Disney version, the animals have names and distinct personalities: The bird is named Sasha, the duck Sonia, and the cat Ivan, and each character livens things up through comedic routines. A beloved favorite in schools and theatersDozens of lesson plans about Peter and the Wolf have been created for students of all ages. Typical of these is one created for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. In this program, students hear the story, then listen to musical excerpts to become familiar with individual characters and their accompanying instruments. This goal is to ensure that students will understand the storyline; be able to pick out each character’s musical motif and signature instrument; anticipate how each theme will sound in the composition; and identify individual instruments, as well as instrument families, by sound and tone color.

Local companies continue to stage imaginative productions of Peter and the Wolf as part of campaigns for music education. For example, Seattle Children’s Theatre put on a local playwright’s adaptation of the story in which an Emmy Award-winning musician recast Prokofiev’s classic musical motifs with contemporary music styles such as the Charleston, the tango, and the two-step shuffle. The creative team enhanced the production with puppetry, movement, and an expanded series of humorous incidents. |

Photo used under Creative Commons from Marina K Caprara

RSS Feed

RSS Feed