|

There is a variety of jobs for music teachers out there, from band and choir directors, to academy and university instructors, to vocal coaches, just to name a few. One thing all these types of music instructors have in common is the variety of professional organizations available to support them in broadening their networks and keeping their skills sharp. Here are a few of the best known and most respected. 1. MTNA – Close to 150 years of networking and advocacy  The Music Teachers National Association (MTNA) is one of the oldest professional groups for music teachers. Established in 1876, MTNA aims to make music study more accessible while highlighting the value of music to the general public. The organization’s 20,000+ members have access to extensive professional development programs, conduits to new performance opportunities for their students at every stage of proficiency, and numerous opportunities to meet fellow teachers, leaders in the field, and potential mentors. Members may also join active forums meant for specific group subsets, such as college professors or independent instructors. Membership includes a subscription to the organization’s flagship publication, American Music Teacher, as well as an online journal and access to a professional certification program. Members can additionally take advantage of discounted conference and programming fees. Though MTNA works in-depth at the local, state, and national levels, members must typically join at the state or local tier to participate in national programs. Any state chapter may request MTNA funding to pay for the commission of new work from a specific composer. From among these commissions, the national organization selects a recipient of its annual Distinguished Composer of the Year award. Also, the MTNA Foundation Fund accepts donations in support of programs that foster the study and teaching of music, as well as its appreciation, creation, and performance. 2. NAfME – A comprehensive teaching and learning resource Like MTNA, the National Association for Music Education, or NAfME, is more than a century old. Founded in 1907, the group has grown to become one of the largest arts-centered nonprofits in the world. NAfME’s focus is comprehensive, making it the sole organization of its kind devoted to every aspect of music teaching and learning. NAfME works to ensure that music students at every level have the resources and access to instruction with highly trained and responsive teachers while promoting rigorous standards for the teaching and learning of music. Like MTNA, NAfME works at multiple regional levels—local, state, and national—and has built a depth of experience and engagement among its members. Members have access to numerous professional development opportunities, and membership is open to teachers working in any type of organization and in any capacity. Teaching Music magazine is only one of NAfME’s publications aimed at working instructors. NAfME’s members share a concern for diversity, inclusion, and access in the music profession. The organization’s noteworthy advocacy efforts include its regular visits to lawmakers to educate them on the importance of music funding. NAfME’s wealth of online resources, such as webinars and other Internet-based development content, is especially useful as the coronavirus pandemic has reshaped the teaching and learning of all subjects. In addition to its value to professional instructors, NAfME offers several resources for students and parents, many of them freely available on the NAfME website. 3. ISME – Promoting music as everyone’s cultural heritage The International Society for Music Education, or ISME, is the leading global organization devoted to music education. It works to enhance the appreciation of the role of music in creating a vibrant, meaningful cultural life for all the world’s people. Affiliated with the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and its non-governmental organization, the International Music Council, ISME maintains a presence in more than 80 nations. A significant part of its mission focuses on championing the right of every person to an enriching and accessible music education, promoting wide-ranging scholarship in the field of music, and upholding the values of diversity and respect among all cultures. ISME traces its beginnings back to a UNESCO conference in 1953, which ended with participant representatives pledging to promote music education over the long term. Today, the organization, headquartered in Australia, continues to emphasize this mission, functioning as a global networking site for music teachers looking for ways to celebrate the diversity of the world’s music and preserve it as a valuable part of humanity’s cultural heritage. Members can join ISME under any of several categories that meet the needs of individuals, students, current and retired instructors, and groups. The 2020 World Conference was slated for Helsinki in August, but due to the global coronavirus pandemic, the event has been canceled. Even in the face of this unavoidable outcome, organizers are committed to publishing all previously accepted full papers as part of its conference proceedings and repurposing the content of accepted presentations as virtual educational opportunities. Folk songs serve as a repository of musical and cultural history in countries around the world and are among the favorite ways for children and adults to learn music appreciation. In addition, it holds a place in music education through approaches like the Kodály Method, a system of music instruction named for its founder, the renowned 20th century Hungarian composer and musicologist Zoltán Kodály. It relies heavily on folk songs as teaching instruments for musical concepts and basic skills. The idea is that teaching children folk songs from their native lands and those of people throughout the world transmits a rich cultural heritage, along with a knowledge of rhythm, lyricism, structure, and form. Folk songs encompass rural and traditional music that originated in a particular region and that were passed down orally from one generation to another. They have also been collected by musicians and music historians, such as Kodály and his colleague, composer Béla Bartók. They devoted years of their lives to traveling the Hungarian and Romanian countryside to collect thousands of traditional ballads and songs. Similarly, the collection known as the Child Ballads is an anthology of English and Scottish folk music dating from the 17th and 18th centuries and amassed by Harvard professor and folklorist Francis James Child. It features numerous pieces, and modern musicians have adapted many for contemporary audiences. One example is Simon and Garfunkel’s “Scarborough Fair.” Here is a look at a few traditional folk songs that continue to be appreciated to this day: 1. “Greensleeves” The haunting English folk song “Greensleeves,” which dates from sometime in the 16th century, first became a registered ballad in 1580. Its simple and expressive lyrics proclaim the singer’s longing for “Lady Greensleeves,” and he laments that she spurns his affections. For the past four centuries, scholars and the general public have been fascinated by and have speculated over the song’s origins. One theory ascribes the composition of its lyrics, tunes, or both to King Henry VIII, in reference of his mistress and later queen, Anne Boleyn. Most historians and musicologists dispute this idea and instead date the song to the later Elizabethan era. This is in part because “Greensleeves” contains Spanish or Italian musical elements that were unlikely to have reached England until the reign of Queen Elizabeth, the daughter of King Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn. Patriotic Irish musicologist and historian William Henry Grattan Flood included the song in his 1905 book on the history of Irish music, in which he claim that it was of Irish origin. However, Flood was known for attributing numerous elements in anything that he fancied to Ireland, often with no supporting evidence. “Greensleeves” is a unique tune, and its reprise is grounded in a melodic and harmonic formula called romanesca. This composition uses a descending descant musical formula built on sequences of four recurring bass chords that create a fluidly-rolling tune. Romanesca was common for singing poetry in the 16th and 17th centuries. 2. “Sur le Pont d’Avignon”“Sur le Pont d’Avignon” (“On the Bridge of Avignon”) is among the best-known French folk songs and a staple of French children’s music programs. The repetitious lyrics tell of a dance on the Saint Bénezet bridge in Avignon, during which “handsome gentlemen” and “lovely ladies” dance all around while moving in the opposite direction from one another, then reverse direction. Scholars trace the song to the 15th century. The bridge itself is named for a young shepherd who purportedly received a call from heaven to build it, and it was created over the River Rhône in the 12th century. In the late 1600s, a flood swept most of it away, although four arches still stand. These remains are today a UNESCO World Heritage Site. “Sur le Pont d’Avignon” and its idea of dancing on a bridge has been discredited by historians, who point out that it was more likely that people danced under it on an island in the middle of the river. Scholars state that the song was first titled “Sous le Pont d’Avignon,” meaning “under the bridge of Avignon.” 3. “A Csitári Hegyek Alatt”“A Csitári Hegyek Alatt” (“Under the Csitári Mountains” in English) is among the most popular Hungarian folk songs and composed in a style that approaches a traditional mode structure. The song’s lyrics relay a sad tale grounded in themes of love and jealousy.

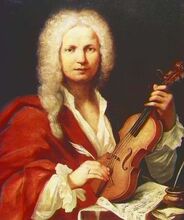

Kodály included “A Csitári Hegyek Alatt” among his special arrangements of key Hungarian traditional pieces, although he added an additional verse. Additionally, the enduring popularity of the song is evident through its frequent covers by contemporary artists who perform it in various styles, such as the British band Oi Va Voi in their album Laughter Through Tears. Andor Kovács and Gyula Kovács made a jazz version of the song’s tune for their 2000 album Guitar-Drums Battle. The artistry shown in a violin performance is highly individual and subjective. Most musicians can achieve competence in playing the instrument. However, if you have shown the interpretative sensitivity, technical virtuosity, charm of personality, or striking originality of expression that moves them into a class by themselves. Here are short biographies of four outstanding performers whose dedication and talent have moved audiences over the centuries. 1. Niccolò Paganini  Image courtesy Wikipedia Image courtesy Wikipedia Niccolò Paganini (1782 - 1840) is perhaps the first musician who can be considered a virtuoso of the instrument. He remains venerated by violinists and the general public alike. His charisma garnered him a cult-like following during his lifetime. His impact on the entire later history of how the violin is played, and how violinists perform on stage, cannot be overestimated. Born in Genoa, Italy, Paganini debuted as a performer the year he turned 11. As a young man, he toured Lombardy while also getting entangled in a number of romantic escapades. At one point he pawned his violin to settle his gambling debts. Biographers record the story that a French merchant then gave him a Guarneri in recognition of his talents. Paganini was also a gifted composer. His 24 Capricci for Solo Violin remain staples of the classical repertoire. From 1828 onward, he undertook tours of England, Scotland, and the Continent, amassing a personal fortune in the process. It was Paganini who commissioned the great French composer Hector Berlioz to create the symphony Harold in Italy, although the virtuoso considered the work unchallenging and never performed it. Paganini’s technique called on a wide-ranging scheme of harmonics and his talent for playing pizzicati. He made up his own innovative methods for tuning and fingering, and displayed a genius for improvisation. A whole raft of legends grew up around this Romantic-era figure, including one that says he got his extraordinary musicianship thanks to a deal with the devil. 2. Jascha Haifetz Jascha Heifetz (1901 - 1974) started his career as a violinist when he was 5 years old. He was soon playing in Berlin, Prague, and Warsaw and performing complex works that included Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto. At age 16, he enjoyed a spectacular debut at Carnegie Hall. The young refugee from Lithuania gave a performance that one music historian has called “like electricity.” Heifetz showed not only an almost unbelievable level of technical proficiency in his instrument, but an immense warmth of feeling and interpretation to match. Heifetz obtained United States citizenship at age 24 and thereafter toured the world. He commissioned a number of violin concertos and himself became a noted transcriber of great works by Bach and Vivaldi into pieces for the violin. Later in life, he taught at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Heifetz was one of the undisputed 20th-century masters of the violin. PBS showcased his legacy in a special broadcast in its American Masters series that called him “God’s Fiddler.” 3. Itzhak PerlmanItzhak Perlman, born in 1945, often tops critics’ lists of the greatest living classical violinists. He has an instantly recognizable bold and exuberant technique. He has remarked that the best technique doesn’t reside in the ability to elicit notes rapidly from the instrument, but in the capacity to evoke rich and surprising tone and color. A renowned teacher and composer as well as a performer, the Israeli-born Perlman has become a pop culture icon. Between the years 1977 and 1995, he racked up 15 Grammy Awards. He is also the recipient of a U. S. Medal of Freedom, a Kennedy Center Honor, and numerous other accolades. Perlman has also made appearances on the children’s educational television show Sesame Street. In a 1981 segment, he movingly demonstrated the difference between “easy” and “hard,” walking onto the stage using crutches (the result of childhood polio) before taking up his violin to play a lively passage. Perlman’s focus on teaching and philanthropy is exemplified in the Perlman Music Program he and his wife established in the 1990s. The program provides training and support to teen string musicians of exceptional promise. 4. Hilary Hahn Hilary Hahn, born in 1979, is known for her dynamic, sensitive interpretations of works by a varied list of composers from Bach to Stravinsky. She began studying the Suzuki method at age 4, made her orchestral debut at age 11 with the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, performed on her first classical recording at 16, and has gone on to receive numerous international awards, including two Grammys before she turned 30.

In 2015, she received her third Grammy for her album In 27 Pieces: The Hilary Hahn Encores. In hundreds of live solo performances, she has been accompanied by the world’s premier orchestras. Hahn has spent her career making classical music accessible to younger audiences. She has performed for films and with alternative rock groups, and has cut a string of successful classical albums, always with a warm and personal approach. Hahn’s popular social media accounts, a signature component of her educational mission, feature running commentary from the point of view of her violin case as it travels with her around the world. In 2010, American composer Jennifer Higdon received a Pulitzer Prize for the violin concerto she wrote specifically for Hahn. Higdon created a piece combining technical virtuoso flourishes with deep, meditative flow, which she tailored to Hahn’s immense lyrical range and ability to negotiate complex changes in meter. On June 7, 2020, Radio City Music Hall in New York will host the 74th annual Tony Awards, honoring Broadway’s best. This year will be the 20th time the Tonys have been presented at Radio City. Radio City is one of the world’s most exciting and glamourous venues for performing arts. Events hosted there include vaudeville, movies, musical concerts, awards shows, and special programs of all kinds. As a result, it has become a beloved icon of American life, and a landmark site for visitors to New York. Here are nine of the most interesting facts you may not know about it: 1. It opened during the Great Depression.Radio City Music Hall opened on a rainy night in New York City on December 27, 1932. That a new theater and entertainment venue of its size would open in the depths of the Great Depression testifies to the longing of people, even in discouraging or desperate circumstances, to find comfort and encouragement in the power of high-quality music and performance. The venue was specifically designed to be a kind of people’s entertainment palace, a place that could bring beauty into everyday lives at an affordable admission price. 2. It has hosted over 300 million visitors since its opening.Opening night saw thousands of people waiting to enter the stunning new Art Deco building. In the almost 90 years since then, some 300 million visitors have enjoyed great performances on its stage. Radio City continues to reign as the world’s largest indoor theater, and one of the most visually magnificent. 3. It was built by John D. Rockefeller.It was John D. Rockefeller who decided to construct Radio City Music Hall. Rockefeller’s idea was to make it one of the cornerstones of his nascent entertainment complex at Rockefeller Center, located in an area he was in the process of renovating from its former rundown state. Rockefeller had leased the Midtown Manhattan property from Columbia University, planning to pursue a collaboration to build a new Metropolitan Opera House. But disagreements over planning—and the financial crash of the Great Depression—killed the project. Rockefeller decided to cut his losses and construct something the world had never before seen. He wanted to give New York City a large-scale entertainment complex, one so spectacular that it would attract commercial tenants and turn a profit even in the most difficult economic climate, when vacant properties were to be found available all over the city. 4. It was part of a partnership between Rockefeller, RCA, and Rothafel. Rockefeller teamed up with RCA, the Radio Corporation of America. RCA owned both the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) and RKO Pictures, whose movies were wildly popular across the nation. Rockefeller and RCA were joined by S. L. “Roxy” Rothafel, a legend in the theater world. “Roxy” oversaw productions that blended movies, vaudeville, and show-stopping design. His industry savvy had brought numerous financially strapped theaters back to life. This team of three then built Radio City Music Hall as the first venue within Rockefeller’s new complex. David Sarnoff, who headed RCA, was the one who gave it the name “Radio City.” 5. It was constructed in the Art Deco style.  Architect Edward Durell Stone was responsible for the imposing Art Deco exterior. However, it was the building’s interior that captivated audiences, both then and now. Designer Donald Deskey, who at the time was relatively unknown, provided the interior decor. The unlikely but inspired choice of Deskey resulted in the stunning entertainment palace we know today. On that opening night in 1932, Deskey’s work thrilled audiences, particularly in contrast to the lackluster show that evening. One critic wrote that the building itself was so magnificent that it did not even require performers. Deskey’s Art Deco esthetic choices focused on bringing clean lines, structural ornamentation, and a European Modernist sense to the design. Attendees first passed inside the building’s elegant lobby, then filed into the Grand Foyer. They could also enjoy eight distinct lounges with smoking areas. Each of these was created with a specific theme referring to another world culture. The entire building was, in fact, a celebration of humanity’s creativity in multiple fields: the arts, science, and industry. Art was a focal point of the overall design. Deskey worked with expert technicians and craftspeople to fill the building with distinctive wall decor, draperies, carpets, sculpture, and murals. He also employed 20th-century innovations in technology in the form of industrial materials such as aluminum and Bakelite, which for seamlessly integrated with stone- and woodwork, gold foil, and marble. Design enthusiasts continue to thrill to Radio City’s interior tactile richness, the variations in tone and color, and the vast interior spaces filled with sweeping, intricately lit arches that evoke the feeling of a sunset overhead. 6. It was constructed with the audience in mind. Radio City’s grandeur covers a lot of space. Its auditorium stretches 160 feet from the stage to the rear. Its ceiling soars more than 80 feet high, and its marquee spans an entire city block. There’s not a bad seat in the house, thanks to Deskey and his design team. A series of shallowly-constructed mezzanines are arranged in such a way that they don’t obstruct the orchestra section below them. Additionally, no columns block the ability to see the stage. The famous “Mighty Wurlitzer” organ was custom-built for Radio City’s theater. It has so many pipes—ranging in size from only a few inches to some 32 feet long—that it takes 11 rooms to contain its many sections. 7. Its stage is state-of-the-art.For performers and audiences alike, one of the central marvels of Radio City is its ingenious and technologically-advanced set of three hydraulically-powered stage risers. Radio City’s stage has won praise from theater experts and is still considered one of the most advanced and best-fitted-out stage spaces in the world. An additional elevator-riser allows technicians to shift the whole orchestra section up or down. A turntable provides the flexibility of making quick scene changes while supporting numerous possibilities for special effects like fog, rain, clouds, and spraying fountains. 8. It has premiered hundreds of movies over the years.Within two weeks of its opening night, Radio City hosted its first feature film, The Bitter Tea of General Yen, directed by Frank Capra and starring Barbara Stanwyck. It wasn’t long until a premiere at Radio City was the best way to ensure a movie’s success across the nation. Over the succeeding decades, some 700 movies have debuted at Radio City. These include King Kong in 1933, National Velvet (starring Elizabeth Taylor) in 1944, White Christmas in 1954, Breakfast at Tiffany’s in 1961, and Disney’s original Lion King in 1994. In 1962, To Kill a Mockingbird also premiered at Radio City, the same theater where the film’s star, Gregory Peck, had ushered as a young aspiring actor. 9. It is has been home to the Rockettes since its opening.Then there are the Rockettes. Previously known, among other names, as the Missouri Rockets, the all-female precision-dancing, super-high-kicking troupe got its start in the 1920s. The group landed in New York after a nationwide tour just as Radio City was preparing to open.

Discovered by none other than “Roxy” Rothafel, the Rockettes opened the first evening’s performance at Radio City Music Hall, and have been its most iconic performers ever since. In the late 1970s, when financial problems almost forced its closing, Radio City was buoyed back up on a wave of nationwide support led, in part, by the Rockettes. Although in the segregated 1930s, the Rockettes’ line-up was all-white, today’s Rockettes are moving toward embracing the full range of American diversity and talent. Most recently, the 2019 Christmas Spectacular show saw several new dancers of color joining the team, as well as a “differently-abled” dancer. A large number of researchers believe that, for people of any age, listening to music while performing tasks at home, work, and school can have a beneficial effect on learning, productivity, and satisfaction. Here are a few facts about this effect: 1. Music improves productivity when working on repetitive tasks. One team at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom found that playing background music while engaging in repetitive tasks—think spreadsheets, counting objects, and reading email—not only makes time go by more pleasantly, it serves to boost productivity. The authors of the study note that this held true for their test subjects even when they were in the midst of a considerable amount of ambient industrial noise. 2. Music is most effective when it is considered pleasant or neutral by the listener.A University of Miami music therapy professor discovered that when people hear music that they personally find enjoyable, they tend to start feeling better. Her test subjects—people who worked in information technology—reported finishing their assignments more quickly when listening to music they liked. Additionally, she discovered that the elevation in mood her subjects experienced propelled them on to come up with better ideas and insights related to their tasks. She concluded that personal choice regarding musical selections is extremely important to the effectiveness of that music in heightening mood and productivity. She went on to observe that over-stressed individuals tend to come to over-hasty conclusions about work tasks. On the other hand, individuals who were able to select their own music could see multiple possible solutions to a problem. Some investigators have discovered, however, that music we neither strongly like, nor strongly dislike, may be best for workplace productivity. A group of Taiwanese researchers at Fu Jen Catholic University found that extreme reactions—positive and negative—to music made it more difficult to maintain concentration. 3. Music triggers the release of dopamine in the brain.Biology tells us that the act of listening to music we enjoy releases hormones called dopamine into the brain’s reward center. This is the same reaction we experience when we look at a beautiful scene, drink in the scent of a rose, or eat a delicious meal. One physician at the Mayo Clinic who has studied the way people at work gain focus from listening to music notes that it takes less than an hour a day to achieve the mood-lifting and mind-opening benefits. 4. Music is most effective at increasing productivity when it is instrumental. One point seems to be consistent across a variety of research studies: the best music for concentration and productivity is wordless. Words that we can understand tend to distract the brain, since they pull us in the direction of trying to make sense of them. One study found that almost half of office employees in the test group were distracted by human speech. Trying to tune out the background noise of others’ voices won’t work if the music has lyrics. It will merely cause the brain to shift its focus. 5. The tempo of Baroque music may facilitate concentration and learning.The tempo of a piece of music has a strong impact on how well it facilitates concentration. Numerous studies have shown that music from the Baroque period in particular—think Bach, Vivaldi, Georg Telemann, Henry Purcell, and Jean-Philippe Rameau—aids learning and concentration, which contributes to longer-term retention of new information. In fact, authors Sheila Ostrander and Lynn Schroeder wrote the book Superlearning 2000, an update to their earlier title Superlearning, to further outline exactly how to use the steady, even beats of Baroque music to learn foreign languages, new vocabulary, and a host of other facts, figures, and real-world skills. Fans of the Super-Learning books say that the techniques and helpful resources the authors offer have helped them speed up their learning, recall much more of what they have read, and fully engage both hemispheres of their brains. Ostrander and Schroeder, who began putting the book together in the 1970s, drew on then-revolutionary research by top psychologists and neurologists. These scientists had discovered that listening to Baroque music in particular was capable of increasing the powers of a person’s concentration and memory. They posited that this was the result of the regular mathematical formulas that lie at the heart of the Baroque tempo. 6. Baroque music may facilitate the production of alpha waves in the brain.The 50- to 80-beat-per-minute tempo of Baroque, researchers have learned, is comparable to an adult’s resting heart rate. This makes it ideal for stimulating the production of alpha waves in the brain. These alpha waves are known for inducing a mood of deep but focused relaxation.

When human beings are in an alpha state—with their brain waves’ frequency measuring from 9 to 14 hertz, or cycles per second—they are far from being passive or inattentive. A person in an alpha state is calm but alert, and is extremely receptive to taking in and processing new information. Most of our daily lives are spent in the active beta state, with brain waves of between 15 and 40 cycles per second. This means the alpha state represents a significant reduction in our normal rhythms, giving us more time and space to notice things we may not have noticed before. Most experts date the Baroque period in classical music from about 1600 to 1750, putting it between the polyphony of the Renaissance and the era of Classicism (the period after the mid-18th century distinguished by the works of composers such as Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, and Schubert). Compositions from the Baroque period are typically marked by their grandiosity and drama as well as the numerous ways in which composers used the technique of counterpoint to express musical themes and ideas. Developments in the music of this period parallel those in the other arts—for example, massive and ornate buildings such as St. Paul’s Cathedral in London and the Caserta Royal Palace in Rome. Venetian Baroque-era churches, built with two opposing galleries, were ideal for the performances of two ensembles of musicians playing at the same time. A complex formThe concept of two voices or groupings in contrast with one another is a central idea in Baroque composition. Concertos (known in Italian as concerti grossi) featured a solo instrument or voice playing or singing along with a full orchestra. They were a favorite among Baroque composers. Baroque music tends to emphasize a bass line set against a melody. A cello, for example, might deliver the bass, while a vocalist sings a melody. The technique of counterpoint is central to the development and performance of Baroque music. Simply put, counterpoint is the art of combination. A composer working with counterpoint will juxtapose two or more separate melodic lines in a single composition. In counterpoint, individual melodic lines are known as “parts” or “voices.” Each part or voice has a distinct melody. The term “counterpoint” is sometimes incorrectly conflated with polyphony. Polyphony refers to the presence of at least two individual melodic lines in a composition. Although counterpoint evolved out of polyphonic music, counterpoint is a much more complicated technique. True counterpoint involves a complex handling of the several melodic lines of a composition to fashion an acoustically and emotionally meaningful and harmonious whole. The organ and the harpsichord are perhaps the instruments audiences most acquaint with Baroque music. During the Baroque period, these instruments offered two keyboards, allowing the musician to transfer from one to the other to create the rich blending of the contrasting sounds. A centuries-old technique that continuesComposers of the Classical period were usually steeped in the techniques of Baroque composition from their early years. Some, like Mozart and Beethoven, would go on to employ counterpoint extensively in their own later works, written well into the Classical era. Counterpoint continues to find favor today among musicians, composers, and even mathematicians, who have devoted much effort to explaining its symmetry and intricacy in terms of numerical relationships. The supreme artistry of BachNumerous critics and teachers have found the Brandenburg Concertos of Johann Sebastian Bach to represent a pinnacle of the development of the concerto grosso form, and of the Baroque style itself. Bach created these works over the span of the second decade of the 18th century, one of the happiest periods of his life. The six compositions masterfully weave together the component threads played by a smaller orchestra and by several solo groups. Music scholars point out that the scale of the Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 features so many soloists that it is more of a symphony than a concerto, in fact. Bach brought in oboes, horns, a bassoon, and a solo violin. And the third of these concertos features performances from no fewer than three cellos, three violas, and three violins. Unique among these concerti, Brandenburg Concerto No. 6 features not even a single violin; instead, it focuses on lower-voiced string instruments. Three centuries after their composition, the rich-toned, lilting Brandenburg Concertos remain among the most popular and beloved works in the classical repertoire. The art of fugueBach was a master of the fugue, and many musicologists revere his late work The Art of Fugue as one of his most significant creations. A fugue is a piece of music—or a part of a larger composition—that offers finely tuned and mathematically pleasing use of a central theme (the "subject") and numerous restatements and reconfigurations of that theme. In a fugue, the subject is taken up by other parts that are successively woven together. A fugue begins with an exposition, introducing the listener to the central subject. The subject then plays out in different parts, becoming transposed into various keys that serve as “answers” to the essential statement of the subject. A fugue can unfold over as many statements, restatements, and key changes as the composer would like, and can be as short or as long as desired, as well. Baroque composers worth knowingGramophone magazine, one of the world’s premier authorities in classical music criticism, recently put out its 2019 edition of the Top 10 Baroque composers.

Bach heads the list, with the Gramophone team noting that he continues to enjoy a status in music equivalent to that of Shakespeare in literature or da Vinci in the visual arts. The publication particularly recommends Bach’s St. Matthew Passion as a supreme example of his musicianship and of the Baroque style. Next comes Antonio Vivaldi, whose lavish, ornate compositions echo the culture of his native Venice at the time. Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons is perhaps the best known of his works today. This lilting, exuberant hymn to the beauty of earth’s changing seasons is known for its exquisite craftsmanship. George Frideric Handel’s lively, upbeat Baroque compositions are other essentials for anyone becoming familiar with the era. His towering oratorio Messiah remains a not-to-be-missed composition for both music lovers and those devoted to the Christian faith. The experts at Gramophone additionally nominate English composer Henry Purcell, composer of Dido and Aeneas and other operas, to this select group. Claudio Monteverdi, remembered as a bridge between Renaissance polyphony and the early Baroque style, also made the list, as did Domenico Scarlatti, Jean-Philippe Rameau, Georg Philipp Telemann, Arcangelo Corelli, and Heinrich Schutz.  Vivaldi | Image by Wikipedia Vivaldi | Image by Wikipedia Antonio Vivaldi, born in Venice in 1678, achieved fame during his lifetime as one of Europe’s greatest composers. His works have continued in popularity over the centuries—his “Four Seasons” and other richly textured concerti, as well as his operas, are still beloved by listeners all over the world. Vivaldi’s influence on the development of Baroque music, particularly on the emerging form of the concerto, cannot be overstated. Even scholars, however, often overlook how he opened doors for the participation of women in music. Here are a few facts about Vivaldi’s work with an extraordinary group of Venetian female musicians, and how they themselves achieved renown for their gifts in an age when few women and girls had such an opportunity. “The Red Priest” and the orphanageVivaldi worked with the church and orphanage of the Ospedale della Pietà in Venice sporadically from 1703 to 1740. An ordained priest nicknamed “Il Prete Rosso” (“The Red Priest”), most likely due to his vivid red hair, Vivaldi soon ceased to administer the sacraments and concentrated on his work as a composer and teacher. At the Ospedale, he served as a violin master and, later, a concert master. He also composed large numbers of works to be performed by one of the world’s most accomplished—and largely unknown—musical groups: a chorus and orchestra made up entirely of orphaned girls and young women. The long history of the orphanage The Ospedale was a creation of the Middle Ages. Founded by a 14th-century Franciscan priest as a charitable home for orphans, it took in both boys and girls who had lost their families to famine, plague, and other horrors that were common in the Europe of that time. It was attached to the Church of Santa Maria della Pietà, which also served as a public hospital. Throughout the Middle Ages and early modern period, such institutions—a combination hospital, orphanage, and musical conservatory—flourished in Venice. The Pietà was one of four major ospedali that made the city a must-visit musical destination until the fall of the Venetian Republic at the close of the 18th century. Marketing a music schoolThe Ospedale needed a continuous supply of generous patrons in order to feed, house, and clothe the increasing number of children within its walls. Its most creative—and best remembered—marketing effort involved establishing a girls’ choir, composed of its orphaned singers and musicians. The school would test each child at around age 9, to see if she had the needed flair for music. If a girl showed promise, the school made sure that she would have access to the finest musical education possible. (Researchers believe that many of the girls were not, in fact, orphans at all but the illegitimate children of noblemen, thus providing an additional explanation for the lavish expenditure of funds on a fine musical education.) Giving young women performers a voiceBeginning in the 1600s, the Ospedale’s girls’ choir performed in religious pageants to which the population of Venice was invited. By the following century, the fame of this orchestra was such that visitors from all over Europe traveled to Venice to hear, incidentally providing significant new revenue streams for the church and orphanage. Some of the young women performers became legendary, earning nicknames based on their talents. There was “Maria of the Angel’s Voice,” for example, and “Laura of the Violin.” But of the hundreds of girls who lived at the Ospedale, only a few dozen at a time had the talent necessary to become members of the orchestra and chorus. Vivaldi’s compositions for the schoolVivaldi became the most famous of all the renowned instructors of the Ospedale’s girls’ orchestra and chorus. He composed numerous cantatas, concertos, and sacred works specifically for his pupils to perform. One stellar example: He created “Gloria in D Major,” one of the finest compositions in the entire repertoire of sacred music, for the group. The girls sang this piece while situated high up in the top-most galleries of the church, where they would be concealed from the curious stares of tourists and the rough-and-tumble public. The fact that they were afforded an additional layer of protection by a latticed grille only served to enhance the atmosphere of lyrical majesty and mystery of the Gloria in performance. Vivaldi built the Gloria’s dozen small movements into a joyous praise song for God and God’s creation, with the music depicting moods from deep melancholy to bursts of happiness. A deeply moving novelIn 2014 American author Kimberly Cross Teter published a young adult novel, Isabella’s Libretto, a work of historical fiction based on the girls’ orchestra at the Ospedale. Isabella, the novel’s protagonist, is an abandoned infant taken in by the orphanage. She grows to be a gifted young cellist with dreams of one day performing a work that she hoped Vivaldi would create especially for her. But Isabella is also a free spirit and an annoyance to the Ospedale’s head nun, who sets out to tame her by requiring her to give cello lessons to a new pupil whose burned face testifies to her escape from the fire that killed her family. Isabella finds the grace within herself to rise to this challenge, even as the passing years school her in the bittersweet changes that adulthood brings. Her favorite teacher marries and leaves the orphanage, reminding Isabella that any girl who leaves is bound by the Pieta’s rules from ever performing music in public again. And Isabella herself must weigh her love for her art with her growing preoccupation with thoughts of a young man who seems to want to pursue her. Her struggles with her decision about which future she wants for herself make for compelling reading and will draw in empathetic readers. A resplendent picture bookStephen Costanza’s 2012 jewel-toned picture book Vivaldi and the Invisible Orchestra mines the same fascinating ground to tell the story of the Ospedale for younger readers. In this treatment, orphan girl Candida becomes a transcriber of Vivaldi’s emerging works, creating sheet music for the use of the performers in the “Invisible Orchestra”—so called because the female players performed from places of concealment. Candida’s value goes unappreciated, until the day a poem she composed finds its way into the sheet music, and her own creative gifts receive their due. In the author’s imagination, Candida’s sonnets provide Vivaldi with the inspiration he needs to produce his “Four Seasons,” perhaps his most famous and beloved work. The Ospedale todayThe Church of Santa Maria della Pietà still bears a nickname signifying it as “Vivaldi’s Church,” even though construction on its present building on the Riva degli Schiavoni was not finished until decades after his death. Today, the church stands adjacent to the Metropole Hotel, which was built up around a portion of the older Ospedale that had housed the music room.

The present church, constructed in the mid-18th century, recently underwent renovation after having fallen into disuse and disrepair and has reopened for concerts. Today, the church’s social welfare outreach program is still in operation, serving its community with early education programs for young children and parents in crisis. Additionally, a museum exhibiting some of the items associated with the centuries-old Ospedale is situated nearby. Teaching the basics of music doesn’t always have to take place in school. While formal music education programs are vital for giving children an appreciation of music as one of the quintessential human activities—and are certainly needed when children hope to pursue a musical career—parents and families can provide numerous informal opportunities to develop their children’s musical gifts. Music has an innate and immediate appeal to almost all children, so get creative and make it one of the focal points in your family life. The following suggestions, advocated by a variety of music teachers and family educators, can help point you in the right direction: Turn “trash” into treasure. Use ordinary items found around your home, office, or yard to produce interesting and captivating sounds. For example, you can start an entire percussion section with a few kitchen and garden tools: Pots and pans, lids, watering cans, metal or wooden spoons, empty jugs, unbreakable bowls, water glasses, and other items can produce a wide variety of tones. Try banging the sturdier items together, or beat them with spoons or ladles to make an impromptu drum set. Fill a series of glasses with different levels of water and gently strike them with a spoon. This latter activity is a wonderful chance to create your own STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts, and math) lesson, as you and your child see firsthand how the amount of water in a glass affects the speed at which sound waves travel and therefore the pitch of the resulting sound. Other items that can produce a variety of sounds for your child’s enjoyment include that bubble wrap you were about to throw away, pens and pencils, or even crumpled-up newspaper or wrapping paper. Get crafty.Making his or her own musical instruments together with adults can add to the fun of a child’s musical education. In addition, reusing items that you would have thrown away can help your family gain a greater appreciation of the need for recycling and purposeful spending. Numerous websites, put together by parents and teachers, offer lively selections of ideas and directions for making a rich array of simple instruments. An old box that may once have held tissue paper can be fitted with rubber bands to fashion a simple guitar. Plastic Easter eggs can be decorated and filled with dry rice, beans, or peas to become wonderful shaker instruments. A paper plate with jingle bells attached to it with string becomes a tambourine. And balloon skins stretched over the tops of a series of tin cans can become an exceptional set of drums. After you create your own instruments, practice them together. See how many sounds you can coax them to produce, and even try writing and performing a musical composition using only the instruments you have made. Experiment together while emphasizing to your child that improvisation and exploration are more important than “perfection.” Connect with real musical instruments.If you can buy or borrow real musical instruments, bring them into your home whenever possible. Young children are likely to be especially tactile, so let them experience what a drum set, a clarinet, or a flute feels like in their hands. A visit to a local museum that has a music exhibit, or to a music store or university music department, can also provide this experience. Investigate whether your community offers musical instrument lending libraries, which are designed to provide access to music education for all people, regardless of income. Such libraries are available in some locations in the United States, but residents of Canada are especially fortunate. Toronto, for example, recently initiated a musical instrument lending program through its public library system. Library patrons can check out violins, guitars, drums, and other instruments, free of charge. Listen together.Bring live and recorded music from as many cultures and time periods as possible into your home. Practice your listening skills, and see if you and your child can recognize the sounds of the different instruments in a composition. Encourage your child to catch the beat by clapping, tapping a foot, or creating a dance in time with the music. Hit the books.Bring home a variety of music-themed books, including picture storybook classics like Zin! Zin! Zin! A Violin, written by Lloyd Moss and illustrated by Marjorie Priceman; or The Philharmonic Gets Dressed by Karla Kuskin, with pictures by Marc Simont. Older children will also find plenty of music-themed fiction in titles such as Bud, Not Buddy by Christopher Paul Curtis and The Trumpet of the Swan by E. B. White. Your local bookstore or public library will likely offer all of these, and many others, as well as informational books about music and biographies of great musicians. Unite music and art.You can also look for coloring books that feature images of musical instruments or music performances. Additionally, a simple internet search using the keywords “musical instruments” and “coloring pages” will yield many free images to download and print for your child to decorate. Creating visual representations of musical instruments and concepts will provide a multi-sensory experience that can deepen your child’s connection to the related art of music.

Whether tone poems are enjoyed in a concert hall or played in a simplified arrangement in school or at home, they offer young music students a rich variety of musical experiences. A tone poem is a musical composition designed for a full orchestra. It is designed to evoke, through the choice of instrumentation, tempo, and arrangement, concrete images and storylines in the minds and hearts of listeners. The titles of many tone poems further help the listener in that they acknowledge a composition’s roots in a famous legend, poem, picture, place, or historical event. A tone poem can conjure up visions of majestic mountains, forests, and waterways; knights on horseback gliding over desert sands; the appearance of magical beings, or the tender feelings between two lovers. And a favorite tone poem can make audiences feel transported, mentally and emotionally, to long-past heroic ages, or into the pages of beloved works of literature. Hungarian composer Franz Liszt is often credited with inventing the form of the tone poem, also known as the symphonic poem, in the mid-19th century. In this era of romanticism, revolution, and rising national consciousness, the form flourished. By the early 20th century, composers such as Igor Stravinsky were still writing richly orchestrated tone poems. However, the form began to shift toward using this type of colorful music as a background for dance performances, rather than as single-unit orchestral pieces. Here are brief summaries of what makes only a few of the best-known tone poems memorable: 1. The MoldauCzech composer Bedřich Smetana completed “The Moldau” after only 19 days of work in 1874. Since then, its central melody has become an iconic national symbol. The piece is one part of a six-section suite titled My Country, in which the deeply patriotic composer depicted the natural beauty and the rich cycle of history and myth of his native land. “Moldau” is the German name for the Vltava River, which flows from high forested mountains through the country lowlands and straight through the center of Prague. Smetana’s piece is by turns mystical, forceful, lively, and majestic, as it conjures up, first, the river’s quiet patter, then its sweep through a folksong-filled plain, to its destination near the capital, the royal seat of the Bohemian kings. 2. ScheherazadeRussian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov debuted his orchestral suite Scheherazade in 1888, offering audiences a collection of musical trips to the stories of the Arabian Nights. The deep, bold opening notes paint a powerful picture of Sultan Shahryar, and the sinuous lilt of the violin portrays his wife, the storyteller Scheherazade, with the later musical themes unfolding the stories she tells like the unrolling of a magic carpet. The four movements of the suite tell the story of Sinbad and his ship on the ocean; the “Tale of the Kalendar Prince,” bringing out the full capacity of the woodwinds to evoke an air of mystery; the tender and richly soulful romance of the story of a young prince and princess; and a finale that brings in themes from each of the previous sections, culminating in vivid images of a festival and the destruction of a ship on a wild, tempestuous sea. 3. FinlandiaIn 1899, Finnish composer Jean Sibelius composed and premiered his now world-famous tone poem “Finlandia” as part of a larger suite. Like Smetana, Sibelius was a patriot who used his music to challenge the rule of an empire over his small country. “Finlandia” was, in fact, originally written to be performed at an event protesting the Russian tsar’s censorship of the Finnish press. The work begins with the boom of timpani and brass to establish a somber and foreboding setting. As woodwinds and strings enter the musical conversation, they help to weave the type of stately atmosphere found in a king’s great hall. After a burst of forceful sound bringing in the sense of the whirlwind of struggle animating the Finnish people, the mood lifts. The piece concludes on drawn-out notes evoking a deep sense of serenity and majesty, as if listeners were looking down on sweeping vistas of dark-green Finnish forests. Soon after its composition, the central theme of “Finlandia” became popular worldwide, with many American communities using the melody for songs honoring cities, schools, and other organizations. 4. Fantasia Walt Disney’s 1940 full-length orchestral cartoon movie masterpiece Fantasia is a contemporary tone poem in itself. The film incorporates Disney’s retellings and re-imaginings of the stories behind several of the best-known symphonic works, including French composer Paul Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. In Disney’s version, Mickey Mouse is the hapless student of magic pursued by a pack of enchanted brooms.

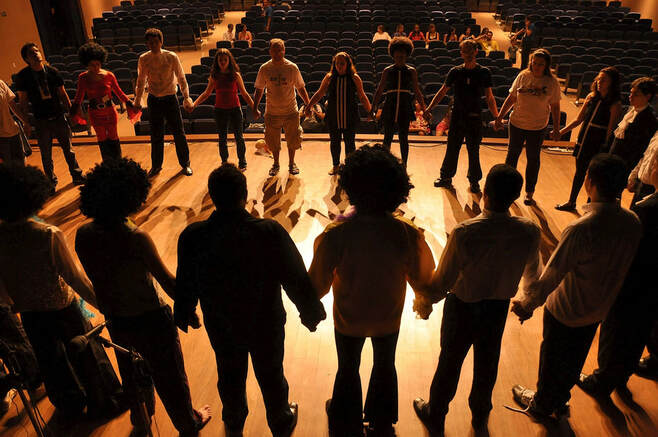

Dukas’ original soundtrack debuted in 1897. He based it on a folkloric tale by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, one of the towering figures in the European literature of the Enlightenment. Dukas’ composition closely follows the sequence and spirit of Goethe’s piece by offering an opening that paints a picture of quiet, but magic-filled domesticity in the sorcerer’s workshop. But then the apprentice enters, represented by a leitmotif uniting oboe, flute, clarinet, and harp. A burst of timpani perhaps signals a stroke of enchantment. Then, through the composer’s use of a triple-time march, the sorcerer’s army of brooms comes lumbering, and then sprinting, to vivid life, carrying one bucket of water after another. Dukas masterfully uses strings to conjure up the flooding cascade of water that ensues before the sorcerer, accompanied by the gloomy moans of the bassoon, returns to chase away all the mischief. At Music Training Center (MTC) in Philadelphia, children can take lessons in music and voice training. They can also participate in an a cappella vocal ensemble, Rock Band classes, or a number of high-quality musical theater productions. Over the years, Music Training Center has nurtured the talents of a number of promising young musicians and performers. The musical theater component is one of the organization’s signature programs. Kids in the upper elementary, middle school, and early high school grades can participate in its Main Stage musical production. Younger kids work on their own Junior Stage and Mini Stage productions. Popular musicals serve as an excellent way to engage kids with learning the basics of musical theater stagecraft. Experts in the performing arts have noted musical theater’s ability to develop a wide range of essential talents and skills in children who are considering making any branch of acting or performing a lifelong career. Further, musical theater training can lay the foundation for the kind of self-confidence, physical and mental stamina and agility, and personal presentation skills that will enhance a young person’s performance in any other type of career later on. There are many reasons to encourage your child to participate in musical theater. Here are four: 1. Musical theater programs are available throughout the countryThe MTC program is only one of many across the country that focus, either year-round or as a special summer experience, on the wealth of benefits that participation in a musical theater production can provide for children. The Performers Theatre Workshop in New Jersey, the Music Institute of Chicago, and San Francisco Children’s Musical Theater are only a few more examples of organizations that offer this kind of vibrant and engaging—and potentially life-changing—programming. 2. Musical theater helps teach movement, communication, and confidence.For example, kids who participate in musical theater training learn a whole set of movement skills. These skills can improve coordination, kinetic awareness, and overall fitness. In addition, training the voice to perform songs in a musical theater production tends to strengthen the vocal chords. They also benefit the performer’s overall voice presentation. This is a helpful tool for leaders and communicators in any field. Experts in teaching musical theater additionally point out that confidence is among the main takeaways from participation for many kids. Musical theater can take performers far beyond their familiar comfort zones. A student who primarily views herself as an actor might be asked to sing in a particular production. Another who thinks of himself only as a dancer might be called on to learn and speak lines of dialogue to convey an emotional experience. These activities might at first give young performers a case of nerves. Ultimately, however, this type of multifaceted training can open doors onto new ideas, build new skills, and create a sense of accomplishment in ways that stay meaningful over a lifetime. 3. Musical theater boosts self-esteem. One dissertation-related study, published in 2017 under the auspices of Concordia University-Portland, found that music and theater studies, individually, offer enormous potential. They can help middle school students develop their self-esteem and their scholastic achievement. The study goes even further by exploring the ways in which the combination of the two subjects in musical theater can lift up middle school students’ sense of self-worth and facilitate their achievement in a number of ways. In this particular study, about a dozen suburban private school students in Minnesota took part in staging a musical theater event. The researcher used direct observation, interviews, school records, and Likert scale surveys to gauge the degree to which the students engaged in a positive or negative way with the experience. The study concluded that if a student came into the production with already-high levels of self-esteem, he or she did not experience an additional boost of self-esteem from participation. On the other hand, if a student had a lower level of self-esteem before the production, he or she was more likely to develop more openness to being flexible and taking on novel tasks during the course of the production. These students also showed increased comfort with the process of change during the production. 4. Musical theater is fun!One remaining important aspect of performing in musical theater: it's fun. Kids of all ages enjoy meeting familiar or intriguing characters from movies, books, or TV shows translated onto the stage.

When they take on the personas of these characters themselves, they can find creative new ways to express themselves. They can also deepen their awareness of their own emotions and let their imaginations take them on new adventures. |

Photo used under Creative Commons from Marina K Caprara

RSS Feed

RSS Feed