|

A 2016 piece in The Atlantic echoed numerous other recent articles noting that increasing focus on academic standards and testing in schools has led to a declining focus on character building and empathy. While parents and teachers are becoming more aware and concerned about this problem, music offers many solutions. Here are seven ways music education can promote social harmony: 1. Developing compassionate citizens.Renowned music educator Dr. Shinichi Suzuki, who originated the Suzuki method, understood that learning to play a musical instrument could be a significant part of learning to develop into a caring human being and a good citizen. In fact, many music teachers view the Suzuki method as being in a class by itself for this very reason. Experienced teachers also note that the same skills acquired when children study music lead to the development of positive character traits such as tolerance, respect, and a sense of perspective. Working together to study and perform a piece of music fosters a sense of common purpose and encourages collaboration with other people who come from a variety of backgrounds and possess a range of viewpoints. 2. Getting people in touch with their emotions.In their book Music Matters: A Philosophy of Music Education, published by Oxford University Press, David Elliott and Marissa Silvermann discuss the emotional component in music. This is a perennial topic in any discussion of music, going back to the days of the ancient Greeks. Both Plato and Aristotle commented on the ability of music to evoke either positive or negative emotions in listeners. Neurologists and psychologists focused on the power of music agree. In fact, sophisticated new research studies show how musical notes and chords can produce corresponding emotional states in listeners. 3. Counteracting bullying.In fact, a 2015 article in Psychology Today magazine even suggests some music is a possible antidote to extreme antisocial behaviors such as bullying and bigotry. The article points out that learning to play a musical instrument beyond the level of bare technical proficiency draws on a host of emotional skills and sensitivities. In order to produce the most pleasing sequences of sounds and reach the hearts of audience members, a player needs a certain level of emotional maturity and expressiveness. A range of talented musicians have opined that music can deepen and broaden an individual’s perspective. As a result, he or she can grow beyond early prejudices and begin to view other people with greater comprehension and appreciation. For example, the late jazz musician Paul Horn was once quoted as saying that music is an extremely useful way to bring people together in greater peace and mutual understanding, easing the burden of communicating across personalities and cultures. Numerous other musicians have specifically noted music’s power to overcome even the strongest racial and cultural prejudices. 4. Reducing violence.A group made up of musicians, producers, and others based at the University of California, Los Angeles created a collective performance space for the expression of a wide variety of world music instruments and genres. They called their collective Westwood Village Entertainment Group. It has worked to facilitate a welcoming environment for a diverse group of musicians, performers, and audiences. The idea emerged out of one young ethnomusicologist’s experiences growing up in a crime-filled neighborhood in New Jersey. The young man found escape through learning to play African drums. Now, because of WVEG, he and his fellow musicians hope to foster a sense of community and welcome. 5. Reminding listeners of relevant events or eras.The canon of popular music is filled with deeply moving, inspirational pieces that seek to heal the rifts and prejudicial attitudes that arise between people. Examples include Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On?” as well as Curtis Mayfield’s “We Got to Have Peace” and the classic hymn of the Civil Rights era, “We Shall Overcome.” 6. Reducing bias and promoting empathy.One study, published in Psychology of Music, centered on a social experiment with elementary school children in Portugal. Their community is composed of lighter-skinned people descended from families with long histories in the European country as well as darker-skinned people whose heritage lies in the African island nation of Cape Verde. Over a period of several months, the researchers introduced one group of young students to songs from Cape Verde in addition to their regular lessons in European Portuguese music. A control group did not receive exposure to the Cape Verdean songs. Before the study, all of the children surveyed displayed a moderate amount of bias against darker-skinned individuals. By the conclusion of the study, however, the children who had been exposed to the music of Cape Verde demonstrated significantly lower levels of such prejudice. The control group showed no change in their negative attitudes. The researchers in this study theorized that, for the children involved, learning to like the music of Cape Verde translated over into learning to like the other children whose families came from Cape Verde. This aligns with a principle identified in psychological research. The idea is that a feeling of similarity or having common interests with another person tends to increase empathy for that person. The researchers further theorized that songs may be particularly valuable tools for fostering feelings of commonality and similarity, and thus of empathy. 7. Strengthening interpersonal relationships.A 2015 article in Music Educators Journal makes a similar point. Its authors posit that the collaborative experience of making music with others involves activities such as synchronization, group problem-solving, imitation, and call-and-response.

All these activities tend to have a positive influence on interpersonal relationships and on individuals’ abilities to work successfully in groups, and thus, on the development of empathy. According to experts, the themes of music are the themes of human life itself. Therefore, learning to make music makes us more human. Learning to play a musical instrument can open up many exciting new adventures for a child and their family. To further encourage your child’s interest and enhance their learning, why not visit one of the following museums on your next family vacation? Music-focused museums can help your child appreciate their chosen instrument even more and see its place in the rich tapestry of humanity’s musical heritage. 1. The Met in New York shows how art sounds. Image by Moody Man | Flickr Image by Moody Man | Flickr The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City needs no introduction as an art museum, but it is often overlooked as a rich source for learning the history of musical instruments. The Met’s world-renowned collections include some 5,000 instruments from all over the world, with some dating back more than 2,000 years. The focus is on demonstrating how musical instruments have developed across cultures and throughout the centuries. “The Art of Music Through Time,” housed in Gallery 684, is filled with objects, audio and video commentary, and related artworks that provide a multisensory illustration of the power of music. Meanwhile, the André Mertens Galleries for Musical Instruments house hundreds of instruments from Western and non-Western traditions. These include a group of Stradivari violins and the oldest known piano still in existence. There’s also “Fanfare,” an exhibit that centers on 75 specific brass instruments—“brass” interpreted as any tubular instrument played via a mouthpiece—that range from ancient hunting horns to a plastic vuvuzela manufactured to commemorate the World Cup of 2014. In addition, the Organ Loft houses the Thomas Appleton Organ, constructed in the first third of the 19th century and one of the earliest American working pipe organs. 2. An acclaimed musical instrument museum in the desert.The widely praised Musical Instrument Museum (MIM) in Phoenix, Arizona, is home to more than 13,000 instruments—about half of them on display at any given time—from almost every country in the world. The museum works with the goal of acquiring instruments of every time and place, with a special emphasis on folk and tribal instruments. One entire gallery is dedicated to modern popular music. In this Artist Gallery, the objects on display honor artists from Pablo Casals to John Lennon, and Elvis Presley to Taylor Swift. Many of the museum’s installations feature audio or video recordings of iconic performances, while the Experience Gallery gives families a chance to actually play some of the world’s representative instruments. In addition, the MIM hosts regular performances that highlight a range of musicians and styles from around the world. 3. A cultural treasure being rebuilt in the Great Plains.The National Music Museum in tiny Vermillion, South Dakota, has received accolades from the New York Times as one of the most important music museums in the world. It curates some 15,000 instruments, representing every part of the world and almost all of its cultures and time periods. The museum’s collections include a viola made by the renowned Andrea Guarneri in the mid-17th century, and one of the earliest grand pianos ever constructed. Its walls also house a wide range of fascinating musical exotica, including stringed instruments crafted to resemble peacocks and harmonicas shaped like goldfish. High-tech exhibits rely on iPod Touch technology to play performance recordings of the instruments on display. Currently undergoing a major reconstruction and expansion, the National Music Museum is set to reopen in 2021. It continues a lively current dialogue with its fans on Facebook, often offering video clips and pictures of some of the pieces in its collection. 4. See Mozart’s piano in Prague.The Czech Republic loves and honors music and musicians. In the 1780s, for example, the capital city of Prague opened its arms to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and he conducted the world premiere of his opera Don Giovanni in its Estates Theatre. So it makes sense that Prague is the site of one of the world’s finest museums of musical instruments. Located in a former historic church in the Lesser Town near the Vltava River, the Czech Museum of Music is a constituent part of the county’s National Museum. Within its walls are displayed some 400 musical instruments, each with extraordinary artistic and cultural value. An architecturally stunning atrium provides a lovely location for a journey through “Man-Instrument-Music,” the museum’s permanent exhibit, which delves into the many connections between people and instruments over time. On view in the exhibits are a variety of stringed and wind instruments. A grand piano that Mozart once used is just one of the extraordinary objects on display. Museum goers enjoy a heightened experience as their journey through musical history is accompanied by musical recordings played alongside the instruments in the exhibits. The museum additionally hosts regular concerts and special exhibitions. 5. Brussels houses musical treasures in an architectural wonder.The Musical Instruments Museum in Brussels, Belgium, is another among the premier museums of its kind in the world. Housed in a restored, half-Neoclassical and half-Art Nouveau building complex, it houses a collection of more than 1,000 instruments ranging over four audio- and video-enhanced galleries that cover a variety of historical and contemporary periods.

The Brussels museum is part of the Royal Museums of Art and History, which makes its Carmentis online catalog, listing each of its instruments, publicly accessible. One fun feature of its website, at www.mim.be/en, is the Instrument of the Month. The Musical Instruments Museum also encompasses a concert hall and a rooftop restaurant terrace with stunning views of Brussels. The Juilliard School, which is housed at the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts on New York City’s Upper East Side, is an educational institution that has helped to further the skills, talents, and careers of numerous young musicians and other performing artists from around the world for generations. Over the years, The Juilliard School has expanded its programs to include a broad array of performing arts curricula, and it now serves as Lincoln Center’s professional education division. It offers undergraduate degrees in music, drama, and dance, as well as a master’s program in music. Its current total enrollment stands at approximately 1,400 students. The following are a few interesting facts about the Juilliard School: 1. Distinguished alumniDesigned as a place to nurture extraordinary talent, The Juilliard School has produced scores of distinguished graduates who include legendary pianist Van Cliburn; cellist Yo-Yo Ma; conductor Leonard Slatkin; contemporary actors Viola Davis, Jessica Chastain, Samira Wiley, and Michael Urie; and Jon Batiste, bandleader on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert. 2. A turn-of-the-century American conservatoryThe school began as the Institute of Musical Art in 1905, when it took up residence at the corner of 12th Street and Fifth Avenue. Founder Dr. Frank Damrosch was the godson of the 19th century composer and musical prodigy Franz Liszt. Damrosch, then the head of the city’s music education program for public schools, worked with a focus on providing American music students with access to the same quality of instruction that was common in the best European conservatories. When the institute opened its doors, it did so with a student body that was five times as large as originally expected, leading to a sudden need for expanded quarters. In 1910, it relocated to a space close to Columbia University. 3. A benefactor’s legacyIn 1919, Augustus Juilliard died, leaving a will containing the largest single bequest to further music education that was unseen up until then. Juilliard, who made his fortune in the textile industry, was thus immortalized in 1924 through a new institution called The Juilliard Graduate School, funded by his bequest under the auspices of the Juilliard Foundation. Two years later, the graduate school merged with the Institute of Musical Art. The new combined school would be renamed The Juilliard School of Music in 1946. 4. Expansion beyond musicThe school, as constituted after 1926, came under the direction of a single president, John Erskine, a popular novelist and a professor at Columbia University. In 1937, Ernest Hutcheson, a widely known composer and pianist, took over as president, followed in 1945 by William Schuman, a distinguished composer. Schuman began an effort to increase the school’s reach by offering not only music courses, but a new dance division, as well. The Literature and Materials of Music program, a pioneering curriculum in the art of music theory, also became a core component of the school during his tenure.  Image courtesy Shinya Suzuki | Flickr 5. An iconic string quartetIt was also under Schuman’s direction that the school established its own in-house quartet, the Juilliard String Quartet, in 1946. The Boston Globe has called the quartet the most important ensemble of its kind ever to be founded in the United States. Today, its members not only champion and exemplify the classical tradition, but they consistently work to expand the repertoire of newer works performed. Its 2018-19 season features works that include a newly commissioned piece by renowned Estonian-American composer Lembit Beecher. Quartet members served as master instructors during their touring seasons, working with students in classes and open rehearsal formats. The group also hosts a five-day-long Juilliard String Quartet Seminar, annually in May. In 2011, the quartet received a National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences lifetime achievement award, the first ever presented to a classical ensemble. The Juilliard School today also hosts a broad array of other performances, including those by its orchestra, wind ensemble, and members of its Marcus Institute for Vocal Arts. 6. Becoming part of Lincoln CenterIn 1968, when Peter Mennin served as Juilliard’s president, he oversaw the creation of a drama studies program headed by powerhouse actor and producer John Houseman. In that same year, under Mennin’s direction, the school rebranded itself with its current name, The Juilliard School, then relocated to its campus to Lincoln Center in 1969. During Dr. Joseph W. Polisi’s tenure as president, Juilliard added new curricula in historical performance and jazz, as well as several new drama and liberal arts tracks and community engagement programs. Damian Woetzel, a former principal dancer with the New York City Ballet, became Juilliard’s president in the summer of 2017. 7. A rich history captured on filmA documentary on the history of the school, which was produced by PBS, features the remembrances of current and former alumni and instructors. In 2018, the documentary became available for streaming online. Titled Treasures of New York: The Juilliard School, the hour-long film includes comments from world-renowned figures in the arts such as violinist Itzhak Perlman and trumpeter and music educator Wynton Marsalis. The film captures the school’s rich history of teaching, learning, and performing, from its inception to its relocation to Lincoln Center. 8. An even stronger international footprintThe Tianjin Juilliard School in China is projected to open in the fall of 2019. The school’s creators envision it as incorporating all of the elements of a true 21st century music conservatory on an international scale.

The brass family of musical instruments takes its name from the material with which they are made, and their booming, brassy sound makes a big impact. The brass instruments that most young students will encounter are the French horn, tuba, trombone, and trumpet. They might also meet the cornet, which is very similar to the trumpet, and the sousaphone, closest in style to the tuba. The euphonium and the baritone are less well-known—their size and range fall somewhere between the trumpet and the tuba. Buzzing mouthpieces, valves, and pipesMusicians play brass instruments, as they do members of the woodwind family, by pushing their breath into the instrument. But, unlike the woodwinds, it is not a vibrating reed, but a metal mouthpiece shaped like a cup, that amplifies the sound and drives it forward as the player’s lips buzz against it. Today’s brass instruments consist of a long stretch of tubing or piping that flares out toward the end like a bell. In order to allow for better and smoother handling and playing, the instruments’ pipes are configured into twists, curves, and curlicues of various types. Attached to the pipes are a variety of valves that allow the player to open or close a range of apertures along the pipe’s length. When a player presses down on various combinations of valves, he or she can vary the sound, loudness, and pitch. The clear, strong sound of the trumpetThe trumpet and the cornet are the smallest and highest-pitched members of the brass family. The differences between the two are miniscule, and their sounds are almost indistinguishable, although the trumpet’s shape is slightly longer and slimmer. Beginning players typically find that neither is an improvement on the other. The trumpet is easy to maintain and to store, with only two body pieces to take apart between one band practice and the next. The instrument’s valves and slides need occasional oiling. The earliest prototype of the trumpet we know today appeared in approximately 1,500 BC. Early artisans began to decorate the horns they fashioned from animal tusks, and eventually from ceramics and metal. But the trumpet remained largely a one-note hunting, ceremonial, and wartime accessory until the latter part of the Middle Ages. It was then that musicians began to realize its artistic possibilities. Baroque composers began to incorporate the trumpet into their compositions, impressed with its clear, ringing tone. By the close of the 1700s, Viennese musician Anton Weidinger had added keys to the instrument, giving it the capacity to produce a complete chromatic scale in all registers. The invention of valves replaced the keyed system, and by the second decade of the 1800s, the first working brass instrument valve ushered the trumpet into the modern orchestral age. Makers of early musical recordings were so taken with the strong, bold sound of the trumpet that they featured it often, and superstar players such as Louis Armstrong made it an indelible part of the American musical experience. Learning to slide with the tromboneThe trombone’s long slide piece increases the length of its tubing and changes its pitch, making the slide analogous to the valves found on other instruments. Like the trumpet, it ends in a bell-shaped piece, but has a larger mouthpiece than the trumpet. The trombone is relatively more challenging to play and to care for than other brass instruments. It’s important to take particular care of the slide and treat it gently—if it is damaged, the instrument becomes unplayable. The trombone’s two-piece structure makes it easy to assemble and disassemble, and, like the trumpet, it simply requires occasional oiling and greasing. Students who have good pitch will be able to know exactly how far to extend the length of the slide to produce a desired tone. Students who are unsure of pitch may have more difficulty in controlling the trombone’s pitch. The trombone arose as a byproduct of the development of the trumpet in the 1400s. Until hundreds of years after its invention, musicians and composers in the English-speaking world called it the “sackbut.” From cor de chasse to French hornThe model for the French horn was based on ancient horns used for hunting. Its name is a bit of a misnomer, since most of the major developments in the instrument took place in Germany. Like its relatives, it was developed during the late-medieval period, when musicians’ experimentation created a variety of new horn types. Seventeenth-century alterations in horn formations produced a model with a larger flared bell, the first recognizably “French horn” type of instrument. This model was originally called the “cor de chasse” and then the “French horn” in English. Complete beginners are not usually capable of attaining great proficiency in playing the French horn, and so should proceed with caution before settling on it as a band instrument. But for a student with an excellent grasp of pitch and solid prior musical training, it can be a good choice. Like other brass instruments, the French horn is comparatively simple to store and to care for. The big and beautiful tubaThe tuba, the brass family’s largest instrument, is also its deepest. It can play both accompaniment and melody, adding surprisingly nuanced and beautiful tones.

Students can obtain tubas of various sizes; it’s important for each musician to identify the size that’s right for them. Younger players who struggle with the full-sized tuba may find that the baritone is a more manageable instrument, at least at first. The tuba’s care is similar to that of other brass instruments, and it consists of at most three pieces. Unlike its cousins, the tuba’s origins lie not in ancient or medieval times. Drawing on previous valved band instruments, two Berlin-based musicians filed a patent for the tuba in 1835. Johann Gottfried Moritz and Wilhelm Wieprecht provided their new instrument, set in the key of F, with five valves. Later variations include the Wagner tubas, small-bore models created specifically to fit composer Richard Wagner’s requirements in his large-scale opera The Ring of the Nibelung. According to the National Association for Music Education (NAfME), early learning music programs should include numerous opportunities for exploration through listening, singing, dancing, and other kinds of movement. In addition, teachers should provide the opportunity for kids to actually play musical instruments. Both learning how to play an instrument and learning about music assist young children in developing critical thinking skills and empathy, and promote positive socialization. By making music together, young children also get the chance to experience a wide range of cultures, learn new words, and develop vital senses involving body and spatial awareness, as well as fine and gross motor skills. Every child has the potential to make music and to develop a lifelong appreciation for it. The key is to provide a rich range of developmentally appropriate musical experiences that allow for participation. In a general early childhood classroom, teachers should emphasize fostering a wide and deep appreciation for music, rather than on training children to attain performance-level proficiency. Here are a few insights, gathered from the NAfME’s website and a range of other parent and teacher resources, about the specific instruments, practices, and activities that can make sharing music with young children especially vibrant and meaningful: 1. Select music literature for the classroom with a focus on quality.The selection of music literature in an early education music classroom should acquaint children with high quality works of classic status or perennial value. These can include traditional folk tunes, the works of the classical music repertoire, and world music produced by a range of different cultures over time. 2. Look for age-appropriateness.Professional educators note that it is vitally important to calibrate the types of materials and activities in an early childhood music classroom to children’s developmental age. Children become bored and will not engage if the material is too complicated or goes over their head. 3. Set up for fun.Teachers can have a container of rhythm instruments, such as maracas, tambourines, shaker eggs, handbells, and other percussion instruments ready for impromptu group music-making. They can also stock a basket with accessories such as scarves, feathers, ribbons, and other things that kids will enjoy swirling, twirling, and dancing with. If the classroom can accommodate it, a microphone is a great way to instill self-confidence in young performers who love to sing. And a quiet listening corner filled with choices of classical, jazz, and world music recordings can offer young children the opportunity to further expand and refine their musical tastes on a self-directed basis. 4. Add some real instruments.Teachers, music educators, and parents tend to recommend certain types of instruments as the most appropriate for young children to become acquainted with at home or in the classroom. These include bells, the xylophone, drums, the piano, and the guitar. 5. Sound the bells.A set of color-coded desk bells can be an easy and fun way for young children to learn about the variety of notes and tones. Their clear, simple tones are easy to distinguish from one another. Bells are easy to play—there are no keys, strings, or anything else to manipulate. An additional advantage is that a typical set of desk bells is tuned to the C-Major scale. Because young children typically understand color long before they can connect the name of a note to a sound or tone, it’s much easier to teach them that the blue bell sounds a certain note than it is to describe it as the “C” bell. In addition, bells are far easier to master at a young age than most other instruments, thanks to the fact that a set of desk bells typically consists of no more than eight notes. 6. Beat the drums.Drums are another favorite with young children, with good reason—they’re simple and easy to understand and to use, and offer the immediate reward of sound. Bongo drums are a good choice for young children’s drums, particularly in the classroom, because of their smaller and more manageable size. Although they don’t help with the development of pitch, playing drums builds coordination, and the associated sounds and movements help kids acquire a sense of rhythm. Another advantage is the limited number of sounds a drum can make, a factor that introduces a welcome predictability and familiarity for the youngest students. 7. Pound the xylophone.A color-coded xylophone is a great way to give a young child an appreciation for notes and pitch. Its clear pitch and lengthy, sustained sounds help with pitch recognition. Some xylophones provide a way to remove and rearrange their components, giving a teacher or parent the flexibility to limit a child to only a few notes at a time for instructional purposes. 8. Strum the guitar.Parents and teachers can purchase small, relatively inexpensive guitars designed especially for young hands. A guitar has the advantage of being portable; a young child can wear it throughout much of the day at home or in the classroom, which allows him or her to make up a song or sing a tune whenever the feeling strikes. Thanks to the many guitar-playing icons of popular culture, the instrument can also seem “cool” and “grown-up” to a young child. In addition, there’s a wealth of resources available for teaching and making music with this popular instrument. There are a few potential drawbacks to the guitar, however. It requires a bit more coordination, time, and practice to produce something that sounds like a melody. The notes on a guitar can also be confusing for young children, as there are multiple ways to produce the same note—for example, there are several middle C’s. In contrast, on the piano, there’s only one. 9. Learn the magic of the piano.A number of music educators recommend the piano as an excellent choice for a first instrument, even for preschoolers. Though more complex than the drums, the piano offers a distinct and organic way of teaching relationships among notes, chords, and types of musical compositions.

The piano also offers an immediate reward, in that there is a one-to-one correspondence between a child’s actions (hitting a key) and the emergence of sound. The instrument can also teach fine motor skills and help a child develop an appreciation for subtle distinctions in pitch. The National Association for Music Education (NAfME) points out that there is still no one comprehensive training program for music teachers on the best methods of teaching to students with disabilities and other special needs. Special education teachers may also be concerned about finding the most appropriate and memorable ways of bringing music into their classrooms. With that in mind, here are a few notes on using music to expand the classroom experience for students with special needs: 1. Extraordinary benefitsMusic holds an immense untapped potential to transform the lives of young people with special cognitive and emotional needs. It can build motor skills, social skills, and the ability to communicate with others. Using music as a tool can enrich the life of a child with special needs by making him or her more self-aware, more aware of the world, and better able to understand the people in it. It can serve as an easily accessible bridge from a child’s own inner world to the worlds of others. Music therapists point out that setting lessons—in any subject—to music makes the material easier for students to process and retain. Music can serve as a motivational tool and a way of keeping track of time. Teachers may find that where other strategies have failed, music may be the key to facilitating communication with students with special needs, particularly those who are non-verbal. Children with special intellectual or developmental needs sometimes show a gift for music. And, even for students with special needs who don’t show an obvious aptitude for making music, the very presence of music in the classroom can help overall educational progress. 2. A total neurological packageAll areas of the human brain, as well as almost all of the human sense organs, receive stimulation from making or listening to music. This translates into music’s capacity to boost cognitive capacities in significant ways. Because music engages multiple senses at once, it has an instant and powerful effect on both hemispheres of the brain, as well as the entire human nervous system. Finnish investigators have discovered that simply hearing music stimulates broad swaths of neuro networks, including those that govern the creative process and coordinated movement. While playing music of any kind, many parts of the brain receive stimulation: the cerebellum, a range of cortexes involved with sensation and movement, the prefrontal region, and the limbic system and its amygdala, which are responsible for responding to and remembering emotions. 3. Enhancing the musical experienceThere are a number of resources that can even create customized music for special needs students, assisting them in distinguishing the sounds of spoken language or serving as aids to memorization and learning. 4. The power of percussionPercussion instruments can be especially meaningful for students with special needs. Drums, shakers, and similar instruments provide an immediate sound in response to a physical activity, which can help sight-impaired students improve their ability to control their own movements and understand the nature of cause and effect. The ability to touch and feel the shapes and physical textures of a variety of instruments is also beneficial, as is being able to feel the sound vibrations that follow a particular action. 5. A sample rhythm programNAfME’s website offers some tips on how to build a structured approach to teaching the simple concept of rhythm to students with special needs: First, start off by, as a group, clapping students’ names. Because our names are so intimately familiar to us, it is an easy way for those with special needs to connect to a beat and a pattern. This type of exercise is doubly valuable in that it reinforces the memorization of classmates’ names as well. The next step includes using common words and phrases in rhythmic clapping. Words can be topical—tied in with an approaching holiday, for example—or can represent everyday things in students’ worlds. Displaying an image of the word or words is additionally helpful for any students who still may struggle with word recognition. At this point, teachers can put background music into the mix to support classroom rhythm games. At the next level, teachers can incorporate the use of color to teach musical notation. Each type of note value can have its own color; for example, blue can indicate a whole note, green a half note, and so on. A posted picture of a word that represents the musical expression, with the color-coded notes beneath it, can provide extra support as students learn to rely only on the notation. As students become more comfortable with this phase in their learning, the teacher can gradually eliminate the pictures and the color-coding, encouraging students to read the original musical notation without any prompts. 6. Pairing music with visual stimulationVisual cues are also very helpful for students with special needs learning to remember song lyrics. By fixing images of the words they are singing above the lyrics, teachers can support students in their processing and recall of the new information. Often, adding movement to the singing of lyrics can serve as an additional mnemonic. 7. Giving music its due in education plansTeachers of children with special needs should ensure that each student’s individualized education plan includes a place for music instruction—and for the joys of creative self-expression that come along with it.

When parents and teachers first think about fiction titles for children on the subject of music, the ones that first come to mind are likely to be picture books. But there are also a wide range of absorbing novels for middle-grade readers, each bringing the world of creating and performing music to life. Here are only a few: 1. The Trumpet of the Swan by E. B. White White is better known as the author of Charlotte’s Web and Stuart Little. However, The Trumpet of the Swan is a worthy addition to a young reader’s bookshelf in its own right. The novel’s protagonist is Louis, a young trumpeter swan that the author named after legendary jazz trumpeter Louis Armstrong. Louis is broken-hearted because he cannot make a sound. He wants to be able to communicate with Serena, a beautiful swan who has won his heart. When Louis learns to read and write, aided by his friend Sam Beaver, he only confuses his swan friends. But when Louis’ father steals a trumpet for him to play, the young swan shows that he is more than a voice. In this, his final book for children, White conveys the joy of music and the equal joyfulness of self-expression. Director Richard Rich created a 2001 animated film adaptation of White’s 1970 masterpiece. 2. Bud, Not Buddy by Christopher Paul CurtisThis Newbery Award-winning title also earned a Coretta Scott King Award for its vivid portrayal of the title character, an African-American boy living during the Great Depression. The 10-year-old Bud, whose mother died when he was only six, sets out on a train to find his missing father, as well as to track down the famous jazz musician Herman Calloway. As he learns about his family’s history, Bud also falls deeply in love with the rhythms of jazz. Curtis’ 1999 book was later turned into a jazz-flavored musical that has delighted young people all over the country in touring performances. 3. Hidden Voices by Pat Lowery Collins This 2009 historical fiction title for mature young people ages 12 and up is subtitled The Orphan Musicians of Venice. It is the story of three teenage girls who live in an orphanage in the early 18th century. However, this particular orphanage has built up an extraordinary program of music education, and that theme pervades the book. The three girls all begin their lives searching for love. They find it in their growing devotion to the musical arts under the tutelage of composer Antonio Vivaldi. But there is danger outside the orphanage walls. Each of the main characters experiences the complexities of life, love, and personal trauma in different ways. The book is a rich depiction of the capacity of rigorous musical study to strengthen the human spirit. 4. Second Fiddle by Rosanne ParryParry’s exciting, sensitive 2012 book is a look at the adventures of Jody, a 13-year-old girl in Berlin in 1990 in the wake of the fall of Communist governments across Eastern Europe and the destruction of the Berlin Wall. Jody, a violinist, lives with her family on an American army base. She and her two best friends are the members of an ensemble string trio who hope to perform in a competition in Paris. But their plans are derailed when they are the only ones who can rescue a young Russian soldier who becomes the object of attempted murder. As the girls try to save the young man by helping him reach Paris, they become embroiled in political intrigue and learn the strengthening and revitalizing power of the art they have chosen. 5. Echo by Pam Munoz Ryan The harmonica is the star of this well-researched and deeply moving novel about musical vocation, identity, courage, and compassion. Ryan follows the story of a particular harmonica through the lives of multiple children at multiple times and places. Their musical stories touch on the tragedies of the Holocaust, the internment of Japanese-Americans in World War II, the prejudices against Mexican migrant laborers in mid-20th century California, and the harsh lives of children in an orphanage. Ryan received a 2016 Newbery Honor Award for the book. The audiobook version of Ryan’s beautifully-written historical and contemporary fable is made richer with accompanying musical performances. 6. I Am Drums by Mike GrossoIn Grosso’s 2016 book, middle school student Sam not only plays the drums, she lives the drums, hearing the beat even in her sleep. Unfortunately, her parents don’t have the money to support her dreams by buying her a drum set of her own. Additionally, her school loses its music program due to budget cuts.

Sam creates a drum kit out of old magazines and books while coping with her father’s job loss and her parents’ constant arguing and lack of understanding of her passion. Her love of music prompts Sam to test the limits of what she is prepared to do to achieve her goals. She even lies to her family about starting a lawn-mowing venture to earn money. The author, a music teacher himself, creates a story based on the real dilemmas many kids like Sam face. He establishes reader empathy for his central character, her missteps and successes, and her dream to be a musician. The lilting, lyrical tones of the flute make it one of the most popular instruments for young musicians and one of the easiest to recognize in an orchestra. Experts recommend that you begin to teach the flute and other woodwinds when your child is old enough to have developed adequate lung capacity—typically by ages 7 or 8—and the dexterity to hold and manage an instrument correctly. The flute, which is also one of the oldest-known instruments, has a fascinating history, as it has developed over time: 1. Ancient OriginsThe flute, which is the first-known wind instrument, was used by Stone Age people. Flutes have been fashioned from animal bone, wood, metal, and other materials. The oldest-known example of a Western-style, end-vibrated flute dates back at least 35,000 years ago. Unearthed near the town of Ulm in Germany, the flute was made from the bone of a griffin vulture. Early flutes tended to be end-blown, played in the same vertical position as the recorder is today. Later evolutions resulted in the side-blown—or transverse—flute attaining the form we now know today. Ancient Sumerians and Egyptians used flutes fashioned from bamboo, eventually adding three and four finger holes that increased the number of individual notes they could play. Ancient Greek flutes were end-blown and had six finger holes. The Romans are known to have played transverse flutes, which may have been introduced to Western Europe by the Etruscans as early as the 4th century BCE. The ultimate source of the transverse flute was likely Asia, reintroduced to early medieval Western Europe via the Byzantine Empire. 2. Medieval and Renaissance Pipes, Fifes, and FlutesMedieval flutes, which were typically wooden, with six open finger holes and no keys, were often paired with a drum as the minstrels’ portable pipe-and-tabor set. The Renaissance witnessed the development of flutes, often made from boxwood, with two groupings of finger holes and a slimmer cylindrical bore. While this new design made the tone lighter and more airy and delicate, the sound from the lower register became more problematic. Military bands continued to use the smaller fife. 3. The Flute Replaces the RecorderThe transverse flute began to displace the recorder in the middle of the 17th century, and before another century had passed, it had moved into a place of popularity among a wide range of composers. During this period, changes in the flute’s size and shape conferred upon it a greater musical range. Its larger chromatic range made it capable of evoking a rich palette of moods, from the pastoral to the sprightly, to dramatic declarations of love and soaring flights of fantasy. In the Baroque period, French musical instrument makers—the Hotteterre family chief among them—introduced major changes. They included the creation of three joints for the instrument, increasing to four joints by the early 18th century. The Baroque flutes also featured a bore that tapered toward the foot end. The alterations permitted cross-fingering in order to play in various keys. They additionally made upper-register volume and tuning better. New sliding joints permitted the flute to be tuned in tandem with other instruments of an ensemble. The designation “flute” in compositions from the Baroque period typically continued to mean the recorder, with the transverse flute becoming commonly known as the “German” flute. 4. A Classical FlourishingBy the early 1800s, the flute had six keys and would soon add two more. These classical flutes, like their earlier Western European counterparts, were usually made of wood with a cone-shaped shaft and six keys. The flute as we know it today took its modern form at the time of the Classical period in music, the era of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. During this time, the flute became an integral part of the symphony orchestra. 5. Baroque and Classical Music for FluteIn 1681, Jean-Baptiste Lully became the first to write the transverse flute into an operatic orchestra. Over the Baroque and Classical periods, a number of composers created compositions showcasing the capabilities of the flute. Early 18th century composer Georg Philipp Telemann’s Twelve Fantasias for flute without bass presents flutists with passacaglias and fugues that demonstrate the many possibilities of the instrument, including the “false polyphony” resulting from rapid changes in tone and subject, with the high and low registers alternating. Mozart wrote his Flute Concerto in G major, No. 1, K. 313, which contains a liltingly expressive Adagio movement, encased by lively Allegro and Rondo movements. Beethoven composed numerous works for the flute. His Serenade in D major, Op. 41, is composed for flute accompanied by piano. The work is a series of six subsections, by turns serene and vivacious, introduced by an overture. Its Andante con variazioni e coda has earned praise from musicians as a supreme example of the composer’s art. 6. Boehm’s Lyrical RevolutionToday, flutists use the term “Western concert flute” to describe modern flutes descended from Western European models. This style of flute is also known as the “C” flute because it is usually tuned to that note on the scale, or as the “Boehm flute,” due to the influence of Theobald Boehm on its evolving design. The German-born Boehm, whose long career spanned most of the 19th century, was the greatest influencer of the way the modern flute looks and sounds. A flutist himself, as well as a goldsmith and artisan, Boehm produced a series of significant innovations in the design of the instrument beginning in 1810. Building on previous ideas of other instrument-makers, Boehm also adopted the idea of using larger tone holes, as well as the use of ring keys. In his iterations of the flute in the 1830s, Boehm provided tone holes organized to create the best possible acoustic values. He also linked the keys through a series of movable axles. He also adapted newly invented pin springs to his instrument and put felt pads on its key cups in order to impede the unnecessary escape of air. He altered the silhouette of the embouchure—the mouth hole—to make it rectangular, and constructed the instrument of German silver, for its superior acoustic qualities. By the close of the 1870s, Boehm was offering his “modern silver flute.” Over the course of his career, he produced a revolution in the way flutes were designed, constructed, and standardized. His basic flute design remains largely in use today. The Library of Congress holds a number of examples of Boehm’s flutes in its Dayton C. Miller collection. 7. Today’s Flute—An Ancient Instrument with a New VoiceModern flutes typically have 16 keyed openings, corresponding to an even-tempered octave. Many contemporary flutes possess a range of three octaves. Today’s flutes are typically made from blackwood or cocuswood, or from silver or a silver and nickel-silver alternative.

Current members of the flute family include the piccolo, the concert and bass (or contrabass) flute, all in the key of C, in increasingly lower registers and with different ranges. The lowest note on the hyperbass flute has a frequency of only about 16 hertz, considered lower than the lower limit of human hearing. Flutists today have a rich repertoire of solo and ensemble pieces to choose from, including works by earlier composers such as Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach, a well as 20th century masters such as Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel, and many others. Pythagoras might have been speaking for numerous others when he said that he found music in the spacings between the planets and geometry in the sounds of strings. Plato wrote of harmonies in mathematics and how they parallel harmony in a just society. Confucius also found numerous eternal truths in the unfolding of pieces of music. These ancient philosophers grasped truths about the interconnectedness of music and mathematics that have become even more clear over the centuries. Here are only a few insights, based on the experiences of musicians and mathematicians, about this close relationship: 1. Activation of analogous skillsMusic students, when tested, tend to show more skill in mathematics than their non-musical peers. High levels of cognitive processing ability and executive function—which involves self-regulation and self-management in order to achieve a goal—are essential for success in both fields. Research also supports the notion that executive function, even more so than overall intelligence, has been shown to influence academic achievement. Learning math ties into the development of executive function by calling on a child to analyze, identify key concepts, and proceed through a series of logical steps. Likewise, learning to play a musical instrument enhances this capacity by, among other factors, drawing on the ability to calibrate motor movements in response to changes of time signature and key. 2. A beautiful symmetrySome mathematicians explain their field by focusing on how they work to extract the essential elements of any given thing and study the characteristics and interactions of those elements on an abstract plane. This type of learning can help students to understand music and can lead to a deeper engagement with the essential elements of a musical composition. Music can inspire students to learn more about mathematics through studying, for example, the properties and manifestations of sound. Innovative mathematics teachers have even brought opera singers into their classrooms to show students how the patterns of mathematics are part of the essence of music. 3. Simplicity within complexityEvery note a composer writes or a musician plays is involved in an intricate web of harmony, rhythm, and mathematical patterns. These patterns tend to be built around elements of symmetry. For example, just as the shapes of regular geometric figures remain the same when rotated, a musical tune can be transposed to another key in a composition such as a fugue. In a Mandelbrot set, a famous fractal, a smaller replica of the entire patterned set can always be found hidden at the core of any other image in the set. So, we might also say that a musical fractal occurs when one theme harmonizes with a slower version of itself. Johann Sebastian Bach, for example, showcased a talent for repeating his themes numerous times throughout a variety of permutations. 4. A composition made possible by mathIn fact, thanks to an extraordinary mathematical insight, Bach had the tools he needed to compose The Well-Tempered Clavier in 1722. The piece consists of a set of masterful preludes and fugues, one in each of the major and minor keys. But Bach could not have created this much-loved work without mathematics. In 1636, the French monk and mathematician Marin Mersenne successfully solved a difficult problem by deriving the twelfth root of the number 2, thus paving the way for the division of the octave into 12 equal semitones. Before this division and the associated method of equal temperament of musical instruments, pieces transposed into new keys often sounded uneven and unpleasing. But after Mersenne’s achievement, musicians were able to work with a 12-part octave, evenly spaced and divided into ratios. They could then write music in every key and transpose easily from one key to another. Bach’s The Well-Tempered Clavier was the first noteworthy example of this musical revolution. 5. How math determines pitchA discussion of pitch is only one way to demonstrate how math undergirds sound. Pitch is based on wave frequencies. All audible sounds are produced by changes in the air pressure of the pockets surrounding a sound wave. The frequency that hits the human ear translates into the perceived pitch. Each note possesses its own individual frequency. For an example of sound waves in action, think of a train whistle. Notice that the sound seems higher-pitched as the train approaches. But after the train goes by, the sound seems lower. As the train speeds toward the listener, the forward movement compresses the arriving air pockets against each other, thus pushing them forward more frequently. As a result, the sound seems higher-pitched. Then as the train recedes into the distance, the air pockets slow in their arrival to the ear, giving a lower pitch. We perceive the most pleasant-sounding chords when we combine notes with sound waves that reverberate in analogous patterns. The mathematical ratios of the intervals between notes give the means of calculating which note combinations produce harmony and which create discord. Frequency is measured in terms of hertz, and notes with higher pitch have a higher frequency. Middle C has a frequency of approximately 262 hertz. This means that, when middle C sounds on a piano, the sound waves that reach a listener’s ear consist of 262 pockets of higher air pressure striking against the ear every second. As a comparison, the E just above middle C sounds at approximately 329.63 hertz. Building an understanding of the physics and mathematics behind pitch also leads students to a fuller understanding of octaves, chords, and other musical elements. 6. Pairing music and math in the classroomWhen teaching music in the classroom, teachers can incorporate math in a multitude of ways. One is to ask older children to identify the parts of a musical pattern, then to restate the rule governing that pattern. They can go on to use their analysis of patterns to make predictions about the future direction of a composition. An exploration of time signatures and chords can also be the basis for lessons in how math and music work together.

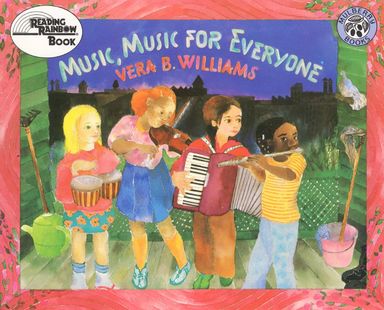

Before younger children even learn the formal concepts of mathematics, they learn through experience about rhythm, repetition, and proportional relationships among musical concepts. They can clap out the syllables of their names, and then see if they can match the number of syllables in their own names to those in other students’ names. They can also echo their teacher, with voice or movement, as he or she calls out and varies notes, beats, and tempos. When teaching music to young children, educators and parents today can choose from a wide range of colorful, fun, and fascinating picture books that will enhance their lesson plans. Here are only a few of the best books for preschoolers and early elementary students that offer lilting texts and multi-layered pictures to help to convey the joy found in music. 1. Music, Music for Everyone

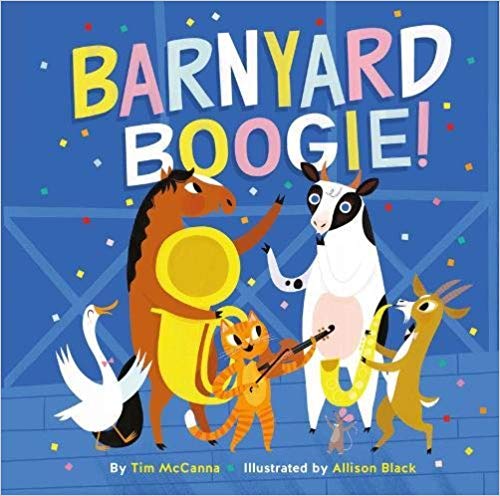

2. My Family Plays MusicMy Family Plays Music, written by Judy Cox and illustrated by Elbrite Brown, showcases the lives of an entire family of musicians in bright and lively cut-paper pictures. Educators have praised the book as a first introduction to the range of musical instruments children can play. Published by Holiday House, it received a Coretta Scott King/John Steptoe Award for New Talent Illustrator after its original publication in 2003. The heroine of the story practices making music with a variety of instruments alongside different members of her family. She tries out the triangle with her father and his string quartet, joins her aunt’s jazz band playing the woodblock, and more. 3. Kat Writes a SongKat Writes a Song, written and illustrated by Greg Foley, is a story of inspiration, creativity, and the ability of music to brighten anyone’s day. Published by the Little Simon imprint in 2018, the book stars Kat, a kitten who is feeling down and lonely on a rainy day. She writes and sings a song, and finds the clouds and rain going away. But the magic really begins when she decides to share her song to lift the spirits of her friends and others in the neighborhood. 4. Barnyard Boogie!

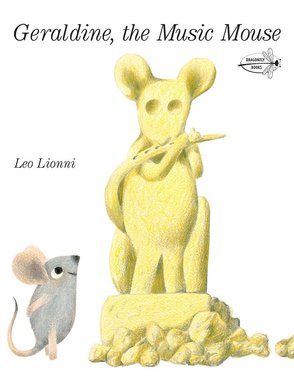

5. Music Class Today!Part of the Music for Aardvarks series, Music Class Today! was written by David Weinstone and illustrated by Vin Vogel. Published in 2015 by Farrar Straus Giroux, Music Class Today! is the simple story of a music class, one shy student, and how to find the inner strength to try new experiences. The lively text and illustrations bring the excitement of making music as a group to life. In addition to his work as a picture book author, Weinstone created the imagination-fueled Music for Aardvarks CDs and classes for young children. 6. Miguel and the Grand HarmonyThe making of Miguel and the Grand Harmony brought together Newbery Award-winning writer Matt de la Peña and Pixar artist Ana Ramírez to create an original work of art based on characters from the beloved movie Coco. The book, published by Disney Press in 2017, tells the story of Miguel. Prohibited from making music, the young boy practices on his homemade guitar in secret. He gets help from the spirit of La Música, who creates the right sequence of circumstances that will allow his dream to come true. The book’s rich illustrations celebrate music’s ability to be a creative force that enhances life’s journey. 7. Geraldine, the Music Mouse

8. Zin! Zin! Zin! A ViolinAnd finally, there is Zin! Zin! Zin! A Violin. The now-classic picture story treatment of the instruments of the orchestra was written by Lloyd Moss, illustrated by Marjorie Priceman, and published by Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers in 1995.

This Caldecott Honor book spotlights the distinctive voices of 10 different instruments in catchy and musically rhyming words set amidst a swirl of saturated pinks, golds, and other colors. It also serves as a counting book, as one by one the instruments and their musicians take the stage. |

Photo used under Creative Commons from Marina K Caprara

RSS Feed

RSS Feed