|

Music and literature have met and mingled countless times, as composers have taken inspiration from poems, plays, novels, and stories to create listening experiences that bring out new dimensions of original literary works. Many of these musical pieces have become classics in their own right, part of the lasting cultural heritage of humanity. One of the great American poets, Langston Hughes (1901 or 1902 - 1967), is today remembered as a writer who gave voice to the hopes, dreams, and common experiences of African Americans. A leading figure of the Harlem Renaissance in New York, Hughes wrote in numerous genres, but is best-remembered today for his lyrical poems that contain a sense of both the joy of living and the painful path of history within their sinuous lines. Hughes drew enormous inspiration from music to feed his creative process throughout his life. Composer Margaret Bonds and Langston Hughes developed an enduring personal friendship that began a decade after she discovered his poems as a teenage music student at Northwestern University in 1929. Their Friendship Began with His Poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” Margaret Bonds | Image courtesy Wikipedia Margaret Bonds | Image courtesy Wikipedia Born in Joplin, Missouri, Hughes wrote “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” shortly after his high school graduation. The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP, published the poem in 1921. Hughes went on to study at Columbia University, becoming immersed in New York’s vibrant cultural scene, which he soon helped shape. “I have known rivers,” the poem opens. Its lines wind down through history, as Hughes’ voices speaks on behalf of the millions of voiceless Black and Brown men and women over centuries who lived, loved, dreamed, and died beside the world’s great rivers, from the Nile, the Euphrates, and the Congo, to the Mississippi. Margaret Bonds (1913 - 1972) was an accomplished musician and composer who had begun composing at age 13. According to Bonds, Northwestern University was a “terribly prejudiced place.” She had made enormous sacrifices to be able to study at a well-known school, and she won prizes in piano and composition during her time there. Yet, due to the practice of segregation, she was not even allowed to use the Northwestern swimming pool. Restaurants in the area refused to serve her. Then one day, going through books at her neighborhood public library outside Chicago, Bonds began reading “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” from Hughes’ first poetry collection, The Weary Blues. Reading it gave her a sense of security, a belief that she, as a young, African American woman, had a rightful place in the world. “I know that poem helped save me,” she said. After They Met, They Began a Long and Fruitful Collaboration Bonds’ discovery of “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” was the touchstone that led her and Hughes to a decades-long artistic collaboration. She finally met him after she finished her university education, at the home of a mutual friend. They became inseparable, “like brother and sister,” Bonds later said, getting to know each other’s families and becoming comfortable in one another’s homes. Bonds even often sent Hughes melodies she had composed, asking him to write lyrics for them. By the mid-1930s, she had set numerous Hughes compositions to music, including “Poème d’Automne,” “Winter Moon,” and “Joy.” Bonds’ interpretation of Hughes’ “Love’s Runnin’ Riot” went on to be performed and recorded by Duke Ellington. In 1940, Hughes and Bonds worked on the revue Tropics After Dark, collaborating with Arna Bontemps, another writer who played a key role in the Harlem Renaissance. Bonds set “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” to music in 1941. Bonds’ music unwinds Hughes’ words at a stately and sonorous pace as it sets to music the historical events in which Black people moved through the world through deliberate or forced migrations. “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” remains perhaps Bonds’ most often-performed art piece, and she always remembered it as among her favorites. Their Collaboration Culminated with the Now-Famous Three Dream PortraitsThe 1959 Three Dream Portraits is a song cycle of three Hughes poems set to music by Bonds. “Minstrel Man,” once notably recorded as a poem read by legendary African American bass-baritone Paul Robeson, is a soliloquy juxtaposing the speaker’s outward mask of frivolity with his inner pain. The irony lies in the fact that this pain went largely unnoticed by the white audiences that typically attended minstrel shows.

“Dream Variation,” the center movement, speaks of “a place in the sun.” It is filled with harmonies gathered from world cultures beyond American borders, and has a joyous sense of movement through dance. The concluding movement, “I, Too,” uses Hughes’ poignant yet ringing words, “I, too, sing America.” Even as the speaker, the “darker brother,” is banished and forced to eat in the kitchen, he feels that when others “see how beautiful I am,” they will invite him to the table, ashamed that they ever excluded him. Critics note that Bonds’ music becomes more self-assured with each of the three movements. It reaches a crescendo of confidence toward the end of “I, Too” that winds down into wistful uncertainty by its concluding notes. This artistic choice by Bonds in the late 1950s mirrored the world around her. The Civil Rights struggle was beginning to gain momentum, with enormous struggle and loss ahead. When Bonds wrote her music for Hughes’ words, the outcome of this struggle was still unknown. Three Dream Portraits remains a deeply meaningful work more than half a century later. Medgar Evers, born in 1925 in the city of Decatur, was a soldier who fought in the invasion of Normandy in World War II before becoming Mississippi’s first field secretary for the NAACP. He was in charge of leading voter-registration drives and directing targeted economic boycotts across the state. In addition, his job involved looking into hate crimes committed against African-American citizens. He launched an extensive investigation into the murder of Emmett Till, the 14-year-old lynched in 1955. As a result, Evers was used to receiving death threats. On one occasion, someone tried to run him over. Another time, someone threw a firebomb at his house, where he lived with his wife Myrlie and their young children. Evers was assassinated in Jackson, Mississippi, on June 12, 1963, by white supremacist Byron de la Beckwith. He was not yet 38 years old. On June 19, 1963, a week after Evers’ murder, President John F. Kennedy sent to Congress the proposed legislation that would become the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, signed into law by his successor, President Lyndon B. Johnson. President Barack Obama officially declared the home of Medgar Evers home a historic landmark in 2017. There have also been a number of songs composed about him. Here are three of the most well-known: “The Ballad of Medgar Evers”The Freedom Singers were one of several noted choral groups active in the days of the Civil Rights movement. The Freedom Singers’ rendition of “The Ballad of Medgar Evers,” also known as “They Laid Medgar Evers in His Grave,” is one of a number of songs memorializing the slain civil rights leader. It was written by Reverend Matthew A. Jones, Sr., a SNCC field organizer who modeled its cadences on the folk song “The Ballad of Jesse James,” making it ideal for choral interpretation. Notably, the lyrics of “The Ballad of Medgar Evers” name his murderer, white supremacist Byron de la Beckwith. Beckwith was not convicted of the slaying until 1994. However, the song lyrics provide contemporaneous evidence that he had immediately been identified as the killer by the community. Strong forensic evidence pointed to Beckwith, who had left his rifle behind at the scene of the crime. Still, the all-white juries in two 1964 trials failed to reach a unanimous verdict. Myrlie Evers never stopped fighting for justice for her husband’s memory. In 1994, Beckwith was finally convicted. He would die in prison in 2001 at age 80. “Too Many Martyrs”As a young man, now-legendary folk singer-songwriter Phil Ochs composed another “Ballad of Medgar Evers” at about the same time as the song written by Jones. The piece by Ochs has a faster tempo, but it also relies on traditional folk ballad rhythms and storytelling style. It begins with the image of “a boy of 14 years” who “got a taste of Southern law.” This is a reference to the murder of Emmett Till. After learning of the Evers assassination, Josh Dunson, a writer for the folk music publication Broadside, was quoted as saying “We’ve already got too many martyrs.” The refrain of the Ochs piece references the many “martyrs” who lost their lives to hate-fueled violence. Ochs later called the song “Too Many Martyrs.” Whatever its title, the song’s relentless pace and highly detailed imagery—describing Evers’ assassination as he stood in his own driveway—continue to elicit a visceral impact on listeners today. Evers got out of his car late on the night of June 12, 1963, after arriving home from a meeting. His assassin used a rifle to fire at him from the cover of a nearby honeysuckle bush, shooting him in the back. Evers died about an hour later. “Only a Pawn in Their Game" Bob Dylan was another folk and protest singer deeply moved by Evers’ murder. Dylan wrote his own tribute to Evers, “Only a Pawn in Their Game." He performed it at the March on Washington on August 28, 1963. Dylan’s song asserted that the murderer was “not to blame,” due to his being “a pawn in their game.” Instead, he depicted Beckwith as just another part of a wider system set in place by others and beyond his control.

Dylan also mentions the many law enforcement officers, white preachers of segregation, Ku Klux Klansmen, and even the governor of the state as other “pawns” in this game. In fact, Mississippi’s former Governor Ross Barnett shook hands with Beckwith in the middle of Myrlie Evers’ testimony at one of the killer’s 1964 trials. Barnett also visited Beckwith in prison. The song’s larger point is that it is not only individuals who need to change, but also a system of entrenched racism. This message continues to be meaningful. However, in 2020, Dylan's lyrics sound hollow and tone deaf to many listeners, particularly because he is white. The song depicts adult human beings as mere chess pieces, rather than as men filled with hatred so strong that it would cause them to support, and sometimes to commit, acts of violence against innocent people. We may not often think of the great composers and musicians of the past as heroes in the sense of being physically brave, or courageous in the sense of putting everything on the line for ideals they believed in. However, behind the great music we know, there are also personal stories of heroism, dedication to causes beyond the self, and steadfast love and kindness that deserve our attention and respect, particularly in today’s chaotic and divisive world. Here are only a few of these heroes from our musical past. Clara Schumann (1819 - 1896)Clara Schumann’s husband, German Romantic composer Robert Schumann, is far more widely known. He created magnificent, intricately virtuosic symphonies and a rich collection of songs and piano pieces, many of them written expressly for her. However, Clara was a highly gifted musician and composer in her own right, and we can attribute her historical neglect to long-standing sexism. In her youth, she was renowned all over Europe as a child prodigy of the piano. Felix Mendelssohn conducted the premiere of her piano concerto, with teenage Clara at the keyboard. She would go on to compose solo pieces and chamber music, and to teach at Leipzig Conservatory. Remarkably, she did all this while caring for her increasingly ill and troubled husband and their many children. The Schumanns had a Romeo-and-Juliet love story. Robert proposed to Clara when she was 18, but her abusive and tyrannical father, Friedrich Wieck, forbade the match. Robert trailed her across Europe as she performed, hoping for a few chance hours together. Friedrich controlled every aspect of his daughter’s life, so she took matters into her own hands and sued him in court. Before the court rejected his claims, her father attempted to gain control of all her concert earnings. He confiscated her piano, stole her letters, and wrote scurrilous slanders against Schumann. Robert and Clara emerged the winners in court and married in 1840. In 1849, Europe was in tumult as revolutions swept the continent, eventually touching the young Schumann family in Dresden. Clara was seven months pregnant, and outside their home peaceful protestors were being gunned down in the streets. Walking through the town the morning after a tense clash, she saw the corpses of those killed and noted the troops knocking on every door to whisk away every able-bodied man to the fighting. Robert Schumann had already shown signs of his severe and life-long mental illness. Clara, desperate to protect him, told the militias he was away from home. To ensure his safety, she devised a plan to spirit him out of Dresden. She left three of her young children at home with a caregiver, to avoid suspicions of the whole family fleeing. Then, she got Robert, their seven-year-old daughter, and herself to the closest train station, talking her way through tense encounters at guarded checkpoints. With Robert and young Marie safely eight hours away, concealed with friends in a small village, Clara returned to Dresden—hiding to avoid detection by patrols of men wielding farm scythes as weapons—and rescued her remaining children from danger. Maurice Ravel (1875 - 1937)French composer Maurice Ravel is likely best known for the orchestral piece Boléro. The composition is used so often in films and television that its rich, stirring music has almost become a cliché. Ravel’s technical mastery, finely tuned sense of melody, and fluidly expressive style are also evident in Pavane for a Dead Princess, his opera The Child and the Enchantments, and the ballet Daphnis and Chloe. Ravel was not a very political man; his personality has been described as intellectual and a little aloof. But in 1914 at age 39, he tried to enlist in the French air force, hoping to serve his country after Austria-Hungary’s declaration of war. Ravel had kept himself anchored to his music for most of his life, separated from the troubles of the rest of the world, but now he felt he needed to become a man of action. Initially, he was rebuffed when the air force thought him too old and unfit. Ravel was a short, slight man who weighed just 91 pounds. However, he was enraged by the deaths of his friends in uniform and wouldn’t take no for an answer. He drove army gasoline trucks near Verdun, where 40,000 men every month were being slaughtered. Hemmed in by enemy fire, he once had to hide in the forest for 10 days. Discharged after contracting dysentery, he was sent home. Critics then and now have often pointed to the violent, clashing rhythms of La Valse (“The Waltz”) as his musical declaration of war against the Viennese enemy. He also composed the piano suite Le Tombeau de Couperin and dedicated each movement to a friend who had died in combat. Benny Goodman (1909 - 1986)Beloved as “the King of Swing,” Benny Goodman was one of the greatest jazz clarinetists and bandleaders the world has ever known. His all-consuming devotion to perfecting his art led to a historic 1938 Carnegie Hall concert in which, for the first time ever, a concert hall audience was treated to a full program of swing music.

This New York-born son of Jewish immigrants from Tsarist Russia started out with a classical training, then quickly became absorbed into the Dixieland and jazz music scenes. He accompanied Billie Holiday in what are now considered landmark performances. Goodman put together his own band in 1934 and went on to create—in solo performances and as a bandleader—what would become some of the 20th century’s most memorable live performance hits and recordings: “Stompin’ at the Savoy,” “Moonglow,” “Let’s Dance,” and scores of others. That 1938 Carnegie Hall concert was historic for another reason, too: Goodman insisted on performing with his racially integrated band. This arrangement was almost beyond the ability of anyone at that time to comprehend. Most performance spaces were strictly segregated. Throughout his career, Goodman worked with integrated ensembles. In the early 1930s, he had at first hesitated to bring Black performers into his band, but his merciless search for the best sound and his commitment to acknowledging common bonds of humanity won the day. One of the first events in American public life to break the color barrier, that initial Carnegie Hall concert featured half a dozen Black musicians, including Lester Young on sax, Lionel Hampton on the vibraphone, and Count Basie and Teddy Wilson on piano. Hampton later recalled that Goodman’s decision to work alongside Black musicians came not from a desire for fame or money, but from the bandleader’s heart. He recalled Goodman saying that the “white keys and the black keys” just needed to be allowed to harmonize. Musicians around the world have paid tribute to civil rights leader and human rights hero Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The tributes began immediately after his death by an assassin’s bullet on April 4, 1968, in Memphis, Tennessee, and have continued over the decades since then. Here are a few of the songs honoring Dr. King that have conveyed grief, remembrance, inspiration, and hope to millions of Americans, as well as to people around the world struggling to assert their rights amid bigotry and violence. 1. “Abraham, Martin and John”“Abraham, Martin and John,” with words and music by rock musician Dick Holler, was written as a tribute to Dr. King and to presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy, who was assassinated just shortly after King was gunned down. It was a tumultuous time, and communities nationwide—the black community in particular—were torn apart by anger and grief. Holler’s spare, repetitive chords, and gentle, evocative, and simple words—as originally recorded by singer Dion DiMucci—seemed just right for the moment. The song references, in turn, President Abraham Lincoln, President John F. Kennedy, King, and Robert Kennedy, each of whom “freed a lot of people” but died violent, untimely deaths amid cataclysmic events that would change the course of history. The song’s four verses are identical except for the name of each man. Each one asks the listener if anyone has seen “my old friend Abraham,” “my old friend John,” and so on. The concluding words paint a picture of the four men walking side by side over a hill together. The words and sentiments may be considered old-fashioned—even simplistic—to some listeners today. But for many who were alive at the time and looked up to King and the Kennedy brothers as the best of America, they can still summon tears and—often—a smile of wistfulness for the bright future that these men stood for that remains only partially realized. 2. “Happy Birthday”“Happy Birthday” by Stevie Wonder is a song written for a didactic purpose, but one whose lyrics and music still bring joy to audiences who may not even be aware of their original meaning. Wonder, the blind superstar singer-songwriter whose poetic lyrics and musically complex and ingenious melodies embody the joys and struggles of the 1960s and ‘70s, has always been an activist. So, he wrote “Happy Birthday” in 1981 as part of a campaign to get King’s birthday declared an official national holiday. At the time, there was vigorous opposition from conservative politicians and interest groups to a federal holiday honoring King. Wonder’s up-tempo beat and lyrics celebrate King and ask how anyone could oppose the national recognition of “a man who died for good.” Wonder’s lively refrain of “Happy Birthday to ya!” is still very danceable and much deserving of celebration. In 1982, Wonder joined King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, in delivering a petition with 6 million signatures on it in support of the holiday directly to the Speaker of the United States House of Representatives. The following year, President Ronald Reagan signed into law a bill declaring Martin Luther King, Jr. Day a federal holiday to be observed every third Monday in January, beginning in 1986. 3. “Pride (In the Name of Love)”“Pride (In the Name of Love)” by the Irish rock group U2 was released in 1984 as the lead single on the album “Unforgettable Fire.” The band’s lead singer, Bono, initially put together a set of lyrics intended to condemn the militaristic focus of the United States under President Ronald Reagan’s administration. But after a 1983 visit to an exhibit honoring King’s legacy at Chicago’s Peace Museum, Bono began crafting the song to highlight King’s achievements, as well as those of other martyrs to the cause of peace throughout history. The finished lyrics echo King’s own phrases, such as “Free at last,” and “One man come in the name of love.” The phrase “pride” in the title is used in two ways in the lyrics. One kind of “pride” that Bono refers to is the pride of aggression and violence. The second is the kind of pride moral heroes like King embodied, pride in being on the side of justice and freedom for all people. 4. “The King”Pioneering New York hip hop composer and performer Grandmaster Flash, with his group the Furious Five, produced another moving tribute to King, with a song simply titled “The King,” which was featured on the 1988 album On the Strength. The song’s beats and rhythms alone serve as an example of Grandmaster Flash’s classic and fresh musicianship, even as its lyrics provide a lasting artistic memorial to King, a man who “brought hope to the hopeless.” “His name is Martin Luther King,” and he dedicated his life to “making freedom ring,” the rap song proclaims. It relates how King, who was fearless in his convictions, was vilified and persecuted as a black man taking constructive action for freedom for all blacks, and it laments the fact that too many turned away from King’s message of peace and hope, during his lifetime and after. 5. “A Dream”“A Dream,” which is rapper Common’s 2006 tribute to King, samples the words of the hero’s most famous speech. The music video for the song incorporates historical footage of King delivering the speech at the March on Washington in 1963.

Common weaves King’s original words and story (“I have a dream”) into his own perspective (“I got a dream”) as a 21st century black man “born on the blacklist” to struggle against enduring racism, but working to find the hope that still endures through the inspiration he draws from King’s words. Common’s performance, featuring fellow American rapper will.i.am, elaborates on King’s words “one day” throughout its lyrics, and adds, of dreams, “I still have one.” The artistry shown in a violin performance is highly individual and subjective. Most musicians can achieve competence in playing the instrument. However, if you have shown the interpretative sensitivity, technical virtuosity, charm of personality, or striking originality of expression that moves them into a class by themselves. Here are short biographies of four outstanding performers whose dedication and talent have moved audiences over the centuries. 1. Niccolò Paganini  Image courtesy Wikipedia Image courtesy Wikipedia Niccolò Paganini (1782 - 1840) is perhaps the first musician who can be considered a virtuoso of the instrument. He remains venerated by violinists and the general public alike. His charisma garnered him a cult-like following during his lifetime. His impact on the entire later history of how the violin is played, and how violinists perform on stage, cannot be overestimated. Born in Genoa, Italy, Paganini debuted as a performer the year he turned 11. As a young man, he toured Lombardy while also getting entangled in a number of romantic escapades. At one point he pawned his violin to settle his gambling debts. Biographers record the story that a French merchant then gave him a Guarneri in recognition of his talents. Paganini was also a gifted composer. His 24 Capricci for Solo Violin remain staples of the classical repertoire. From 1828 onward, he undertook tours of England, Scotland, and the Continent, amassing a personal fortune in the process. It was Paganini who commissioned the great French composer Hector Berlioz to create the symphony Harold in Italy, although the virtuoso considered the work unchallenging and never performed it. Paganini’s technique called on a wide-ranging scheme of harmonics and his talent for playing pizzicati. He made up his own innovative methods for tuning and fingering, and displayed a genius for improvisation. A whole raft of legends grew up around this Romantic-era figure, including one that says he got his extraordinary musicianship thanks to a deal with the devil. 2. Jascha Haifetz Jascha Heifetz (1901 - 1974) started his career as a violinist when he was 5 years old. He was soon playing in Berlin, Prague, and Warsaw and performing complex works that included Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto. At age 16, he enjoyed a spectacular debut at Carnegie Hall. The young refugee from Lithuania gave a performance that one music historian has called “like electricity.” Heifetz showed not only an almost unbelievable level of technical proficiency in his instrument, but an immense warmth of feeling and interpretation to match. Heifetz obtained United States citizenship at age 24 and thereafter toured the world. He commissioned a number of violin concertos and himself became a noted transcriber of great works by Bach and Vivaldi into pieces for the violin. Later in life, he taught at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Heifetz was one of the undisputed 20th-century masters of the violin. PBS showcased his legacy in a special broadcast in its American Masters series that called him “God’s Fiddler.” 3. Itzhak PerlmanItzhak Perlman, born in 1945, often tops critics’ lists of the greatest living classical violinists. He has an instantly recognizable bold and exuberant technique. He has remarked that the best technique doesn’t reside in the ability to elicit notes rapidly from the instrument, but in the capacity to evoke rich and surprising tone and color. A renowned teacher and composer as well as a performer, the Israeli-born Perlman has become a pop culture icon. Between the years 1977 and 1995, he racked up 15 Grammy Awards. He is also the recipient of a U. S. Medal of Freedom, a Kennedy Center Honor, and numerous other accolades. Perlman has also made appearances on the children’s educational television show Sesame Street. In a 1981 segment, he movingly demonstrated the difference between “easy” and “hard,” walking onto the stage using crutches (the result of childhood polio) before taking up his violin to play a lively passage. Perlman’s focus on teaching and philanthropy is exemplified in the Perlman Music Program he and his wife established in the 1990s. The program provides training and support to teen string musicians of exceptional promise. 4. Hilary Hahn Hilary Hahn, born in 1979, is known for her dynamic, sensitive interpretations of works by a varied list of composers from Bach to Stravinsky. She began studying the Suzuki method at age 4, made her orchestral debut at age 11 with the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, performed on her first classical recording at 16, and has gone on to receive numerous international awards, including two Grammys before she turned 30.

In 2015, she received her third Grammy for her album In 27 Pieces: The Hilary Hahn Encores. In hundreds of live solo performances, she has been accompanied by the world’s premier orchestras. Hahn has spent her career making classical music accessible to younger audiences. She has performed for films and with alternative rock groups, and has cut a string of successful classical albums, always with a warm and personal approach. Hahn’s popular social media accounts, a signature component of her educational mission, feature running commentary from the point of view of her violin case as it travels with her around the world. In 2010, American composer Jennifer Higdon received a Pulitzer Prize for the violin concerto she wrote specifically for Hahn. Higdon created a piece combining technical virtuoso flourishes with deep, meditative flow, which she tailored to Hahn’s immense lyrical range and ability to negotiate complex changes in meter. Every young musician deserves to know more about the fascinating talents who came before them, and today’s publishers offer a rich variety of musical biographies designed to captivate and inspire children. Read on to learn how the recent spate of musician biographies are standing out. Getting to know great talent in a whole new wayThe Who Was/Who Is series of junior biographies makes learning fun with clear, easy-to-read text and illustrations bursting with pizzazz. This series, published by Penguin Workshop, has quickly achieved cult status among elementary-age readers, as well as teachers, librarians, and parents. While many of the biographies in the series cover presidents, scientists, and explorers, many others focus on noted singers, composers, and instrumentalists. For example, young readers can explore the life of Aretha Franklin, a gospel singer born in segregated Memphis, Tennessee, who used her talent to go on to become the one and only Queen of Soul. Franklin exerts a cultural and artistic influence that continues to transcend her death in 2018. Most of the biographies of musicians in this series cover talent from the second half of the 20th century and beyond. Bob Marley, Dolly Parton, Selena, Pete Seeger, Stevie Wonder, and the Beatles are only a few of the figures in popular music whose biographies join Franklin’s. But the series additionally explores a bit of the more-distant musical past with a book on the phenomenal jazz trumpeter Louis Armstrong, who rose to fame in the 1920s. It also transports readers to the world of classical music through its biography of composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Each of these titles gives a wide-ranging overview of its subject’s life and work, providing all the basic information a student would need for a beginning report. An added element of fun in this series comes from the eye-popping cover art—each book’s subject is depicted in caricature with an oversized head set against a colorful, action-packed background. So immediately recognizable are these covers that the books are affectionately known as the “Big Head” biographies. Learning about composers can be funThe Getting to Know the World’s Greatest Composers series, published through Scholastic’s Children’s Press imprint, offers light-hearted but informative looks at some of the great Baroque, classical, and contemporary masters. Written for the grade-school market, this series combines primary source reproductions of historical documents with engaging, color-packed cartoons. The mix of humor with report-ready information and stirring anecdotes about the composers’ lives makes the entire series a winner. Johann Sebastian Bach, George Frideric Handel, Ludwig van Beethoven, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, George Gershwin, and Duke Ellington are only some of the composers represented in this series, each with their own 40-page biography. Turbulent times unite a young pianist and a presidentBooks on individual musicians can fascinate both children and adults, as evident by the recent spate of creatively designed, richly illustrated biographies. Many focus on the highly talented black, brown, and female composers, singers, and musicians that were previously neglected by history and who are now receiving much-deserved attention as our understanding of their contributions fills in the gaps in humanity’s diverse musical heritage. In Dancing Hands: How Teresa Carreño Played the Piano for President Lincoln (Atheneum, 2019), renowned author Margarita Engle teams up with award-winning illustrator Rafael López to present the true story—in lilting free verse and fanciful washes of color—of a child prodigy on piano who became a young composer and a popular performer in her native Venezuela. In 1862 revolution forced her parents to escape with 8-year-old Teresa to the United States, where very few people spoke her language. And this new homeland was fighting its own divisive war. But Teresa’s love of music sustained her. In the US, people called her “Piano Girl,” and she became famous for her ability to interpret any genre of music. When she was only 10 years old, Teresa received President Abraham Lincoln’s invitation to play at the White House. The book itself, according to Kirkus Reviews, offers a “concerto for the heart,” as Teresa tries to lighten the burdens of the wartime president through her art. A sweet voice too soon silencedIn Harlem’s Little Blackbird: The Story of Florence Mills (Random House, 2012), the acclaimed author-illustrator duo of Renée Watson and Christian Robinson bring the story of one of the world’s greatest singers to life. Florence Mills was the daughter of former slaves. Born just before the turn of the 20th century, she first graced the stage at age 5 and became a celebrated performer in Harlem nightclubs and on Broadway. Known for her sweet, soft voice, she captivated audiences until her untimely death at 31. In 1926 Florence won a lead role in Blackbirds, a musical that would take her on an international tour and provide her signature tune (“I’m a Little Blackbird Looking for a Bluebird”) and her nickname. But Florence also experienced the deep racism endemic to the era. During her short life, she fought for the rights and creative freedoms of African-American performers, and generally supported the cause of civil rights. So beloved was she that, after her death from an infection following surgery, tens of thousands of mourners filled the streets of New York City outside the church where her funeral took place. The book offers a moving and gorgeously illustrated account of how this multi-talented performer pursued her dreams, thrived despite injustice, and touched the lives of millions. A modern-day personification of New Orleans’ exuberance “Trombone Shorty” needs no introduction to many contemporary music lovers. A New Orleans-born trombone player, bandleader, singer-songwriter, and New Orleans Jazz Fest headliner, 34-year-old Troy Andrews became a maestro of the horn as a young child. His skills are so renowned that a popular club in his Tremé neighborhood was named Trombone Shorts in his honor when he was just 8.

Andrews picked up his nickname early, when he was still only half the size of his instrument. His nickname serves as the title of his picture book autobiography, illustrated by award-winner Bryan Collier and published in 2015 by Harry N. Abrams. Andrews’ book welcomes readers with “Where y’at?” in true New Orleans fashion. He details his early life as a budding African-American musician in a family of musicians, as well as how he grew up making and playing his own instruments out of items from junk heaps until he started patiently learning how to play a dilapidated old trombone he found one day. Andrews’ true story, coupled with Collier’s dynamic pictures that embody the rhythms of New Orleans jazz, will provide plenty of inspiration to children and grown-ups alike. When students of any age are learning about music, they will find their studies enriched by learning about the history of different musical forms. The following survey of medieval Western music can serve as one doorway into this topic for young musicians, as well as for adult learners interested in the musical history of Europe. Defining an era beyond the stereotypesThe stereotypical view of anything “medieval” conjures up images of dank, fusty monasteries, brutal warfare, and stagnation in the arts and sciences. However, this is far from the truth. The Middle Ages in Western Europe were years of great creativity in the arts, sciences, and exploration. Authorities differ on which time span precisely defines the Middle Ages. The most generous reckoning begins the period at the fall of the Roman Empire in the late fifth century and ends it in the late 15th century AD. A world centered on prayerThe medieval period was characterized by the central place of liturgical music as both high art and a daily companion for the nobility and common people alike. The practice of singing psalms and setting prayer to music dates back much earlier than the Middle Ages, into the beginnings of human history. While much of this ancient religious music was performed a cappella, instruments often lent their voices to the mix, enhancing the sound. The medieval Christian church took many of its cues from ancient Jewish sacred music, in forbidding the participation of women’s voices after the late sixth century AD and limiting or curtailing instrumentation. In the church, mass was the chief occasion for the performance of this music, sung by priest, congregation, and choir. The choir typically filled an “answering” function, responding to the themes of the main part sung by the priest. The human voice as instrumentThe long tradition of prayer through song reached a pinnacle in the development of Gregorian chant, a variety of plainchant, during the ninth century AD. Gregorian chant is still often used today in Catholic ritual. This style of plainchant puts the religious text at the heart of the composition. The human voice is the only instrument used. The music of Gregorian chant is described as monophonic—it consists of one melody, sung in unison. The chant serves to frame the words of the prayers, rather than to overpower them. The majority of Gregorian chants originate in the Latin Vulgate, the version of the Bible in widespread use in medieval Europe. Although most Catholic congregations today celebrate mass in the community's vernacular language, traditional Gregorian chant holds an honored place, both esthetically and liturgically, in modern Catholic culture. Its popularity with both religious and secular audiences is attested by the many recordings now available. Hildegard von Bingen – a composer of mystic devotionHildegard von Bingen, later Saint Hildegard, was born in Germany at the close of the 11th century and died near the end of the 12th. This abbess, mystic, and prophetic visionary is considered one of the first and most talented female composers. Her monophonic works are characterized by soaring lyricism and a deeply felt spirituality. St. Hildegard set dozens of her own poems to music, assembling them into a collection entitled Symphonia armonie celestium revelationum. She was also a scholar who wrote widely on science and medicine and traveled as an itinerant preacher. Numerous musical ensembles have produced recordings of St. Hildegard’s surviving compositions in recent years, and contemporary audiences continue to find them musically and spiritually rewarding. Contemporary collections of her music have titles that reflect her mysticism: Canticle of Ecstasy, Music for Paradise, and A Feather on the Breath of God are only a few examples. Moniot d’Arras – exemplar of the trouvère estheticOne enduring tradition that flourished particularly in the later Middle Ages was that of the secular romantic balladeers and traveling entertainers known as troubadours and trouvères. Lutes, citterns, and other stringed instruments frequently accompanied these musicians' compositions, although their vocals often stood alone. The city of Arras, France, in northern France was noted as a center of the delicate and refined trouvère style. The trouvères’ style evolved roughly in tandem with that of the troubadours, although the trouvères typically composed lyrics in their northern French dialect, and the troubadours drew from the vernacular native to southern France, the langue d’Oc. One monk, Moniot d’Arras, earned widespread recognition as a composer in the early 13th century. While much of his output was focused on liturgy, many other pieces extol the culture of chivalry and courtly love between a nobleman and his lady. These were often the main subjects of troubadour and trouvère compositions. The sacred and the secularThe traditions of the troubadours and trouvères were part of the larger growth of non-sacred medieval music from about the 13th century onward. The ballade, the rondeau, and the virelai were the three leading types of secular compositions in France at this time. Guillaume de Machaut – lyricist supremeGuillaume de Machaut, considered today one of the towering figures of medieval European music, was born at the beginning of the 14th century and is thought to have lived well into his 70s. He wrote in both French and Latin.

Machaut composed one of the first polyphonic treatments of the mass, a development moving away from the monophonic plainchants. Polyphonic music features two or more independent melodies. Machaut's dozens of motets demonstrate the full flowering of this type of music. In 1337, Machaut became the canon of the cathedral at Reims. He wrote poems and musical compositions, with experts today viewing him as a master lyricist and versifier working in the then-current Ars Nova (polyphonic) style. Machaut also used and reworked the courtly love theme, creating beautifully constructed poems that blend technical virtuosity with lyricism. For many young children, the percussion instruments are the most fun to play and learn. Striking, shaking, or clanging these instruments produces an immediate response that the child can hear or sometimes even see. This easily grasped one-to-one correspondence between the child’s actions and the instrument’s sound is a big part of the appeal. Playing a percussion instrument is also valuable because it helps people of all ages improve their physical coordination, dexterity, and motor skills. In addition, percussion instruments give music students the chance to let loose creatively in ways that few other instrument types can equal. Researchers have even learned that drumming and practicing other percussion instruments can reduce stress and even improve the immune system. For all these reasons and more, percussion instruments are justifiably popular with student musicians, professionals, and audiences around the world. The following is a closer look at a few members of this truly global family of musical instruments. This list focuses on some of the more seldom-discussed instruments in the percussion family, and thus omits the piano and the many types of acoustic and electronic drums that are popular in the U.S. The boom of the timpaniIn Sergei Prokofiev’s classic Peter and the Wolf, an imaginative musical romp through the instruments of the orchestra, the crash of the timpani announces the arrival of the hunters. Timpani, also known as kettledrums, entered the Western musical world during the Middle Ages, imported by returning Crusaders and Arabic warriors arriving in western and southern European ports. Timpani came to be used in connection with trumpets to herald the arrival of aristocratic cavalry troops onto a battlefield. Timpani consist of large, round, copper-bodied drums shaped like half of a sphere. Their drumheads consist of sheets of plastic or calfskin stretched tight across the opening. A player produces sound by striking the instruments with sticks or mallets made of wood or tipped in felt. Timpani can be tuned to produce a variety of pitches when their drumheads are loosened or tightened via an attached foot pedal. In a typical orchestra, a single musician will play four or more timpani in a range of sizes and pitches. Playing the timpani calls on all the performer’s skills of attention and sense of pitch, since a typical orchestral piece calls for multiple tuning changes. The xylophone’s flexible rangeThe xylophone’s early history lies in Asia, most scholars believe, before it spread to Africa and then to Europe. The instrument’s name derives from an ancient Greek word that refers to its wood-like tones. The common denominator among the many types of xylophones available today is that the typical xylophone consists of a set of keys, or bars, organized in octaves, like piano keys. Affixed beneath the keys are a series of resonators, or metallic tubes, which produce the sound. Xylophones can be simple toys for the youngest children or sophisticated, multi-octave orchestral instruments. The xylophone player strikes the keys with a mallet. Mallets are produced in varying degrees of softness or hardness; changing the pitch of the xylophone involves using a different type of mallet or changing the way one strikes the keys. The xylophone’s close relatives in the percussion family include the larger and more mellow-toned marimba, the smaller and jingly-voiced glockenspiel, and the vibraphone. The Jazz Age vibraphoneInvented in the 1920s, the vibraphone is distinguished by its metal keys and resonators and by the addition of little spinning discs, or fans, in its interior. These small discs are electrically powered and are arranged under the keys and over the resonators. A player uses felted or wool-tufted mallets to strike the keys. He or she tunes the vibraphone by means of a motor that turns a rod connected to the discs. The resulting sound is the type of shifting, sliding pitch that’s referred to as vibrato when produced by the human voice. The vibraphone has found extensive use in the popular jazz repertoire of artists such as Lionel Hampton. The instrument’s first appearance in an orchestra was in the 1937 Alban Berg opera Lulu. The cymbals – the orchestra’s alarm clockThe crashing of the cymbals in the orchestra makes everyone take notice. A set of these ultra-loud percussion instruments consists of a pair of large discs, ranging in size from 16 to 22 inches in diameter. These discs are typically fashioned of spun bronze. A player hits the cymbals together, or in the case of suspended cymbals, strikes them with a mallet. In general, larger cymbals produce lower sounds. The waterphone’s New Age appealThe waterphone is a newer innovation in percussion. Patented in the 1970s and based on a Tibetan water drum and other instruments, the waterphone consists of a bowl of water, a resonator, and a series of differently sized metal rods. A player uses a mallet, bow, or his or her own fingers to produce sound by striking the rods. The vibration causes the water to shift in the bowl, thus altering the shape of the resonance chamber and creating a whole range of gliding sounds and echoes. Musicologists have described the waterphone’s sound as mysterious and otherworldly, and the instrument is noticeable in many television and film soundtracks. The triangle’s thousand-year-old lilt The triangle is a simple steel bar bent into the shape of an equilateral triangle, with part of one corner left open. The player strikes the instrument with a simple steel rod.

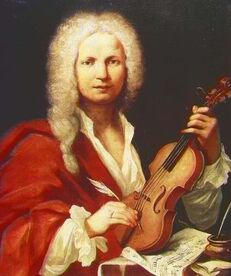

In use at least since the Middle Ages, the triangle often featured an attached set of jingly rings until the early 19th century. As European audiences of the 1700s demanded music in the Turkish style, Western musicians paired the triangle, the cymbals, and the bass drum into an ensemble with the aim of replicating the popular Turkish Janissary sound. The triangle’s piercing pitch is audible even over the sounds of a full orchestra. Accordingly, classical composers tend to use the triangle sparingly, often to add punctuation to a composition. According to the National Association for Music Education, there are a few important qualities that make for an outstanding music teacher. These include strong communication skills, an understanding of how to make learning the rudiments of music worthwhile, the ability to command respect, and a capacity for forging emotional connections with students. Any list of the world’s notable music teachers throughout history would include the following talented individuals, who were also accomplished composers. Read on to learn about their lives, their music, and what they taught their students. Antonio Vivaldi – Leader of a girls’ orchestra Image by Wikipedia Image by Wikipedia By the time of his death in the mid-18th century, Italian composer and priest Antonio Vivaldi had authored hundreds of pieces of church music, concerti, operas, and other compositions. Best known today as the composer of The Four Seasons series of concerti, he exemplified the Baroque sensibility. His music is filled with complex, bravura passages that highlight the solo capabilities of individual instruments. Vivaldi was also a teacher, working at several different schools of music over his career. When he was just 25 years old, he became master of violin with the Ospedale della Pietà, a Venetian school for orphaned children. While serving in this capacity over some 30 years, he managed to compose the bulk of his major creative works. At the Ospedale, the boys were taught skilled trades, and the girls learned music. Vivaldi’s leadership of the girls’ orchestra and chorus brought international fame to the school. The group performed at religious services and often at special events intended to make an impression upon powerful visitors. The girls performed, however, concealed behind a set of gratings, supposedly for the purpose of safeguarding their modesty. Antonio Salieri – Villainous or defamed?Thanks in part to Milos Forman’s movie Amadeus, the dominant image of Antonio Salieri is a jealous villain who helped to drive his rival Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to an untimely death—or possibly poisoned him. But recent investigations have shown that there was likely far less substance to the feud between the two men. Newer biographies and recent performances and recordings of his music, including an album by Cecilia Bartoli, are beginning to show us that Salieri was a talented composer, with a personality that may have been cantankerous. Newer research also shows that he was viewed by contemporaries as a generally friendly, industrious, and occasionally even humorous man. Salieri’s creative output includes several operas in multiple languages, as well as chamber music and works for sacred occasions. Only six years Mozart’s senior, Salieri would live to the age of 74 and eventually see his powers as a composer dwindle, though he took on a roster of exceptionally gifted pupils. These included Ludwig van Beethoven, the German operatic composer Giacomo Meyerbeer, Franz Liszt, and Franz Schubert. Historians recount the story of how Salieri spotted the seven-year-old Schubert’s talent and began teaching him the basics of music theory. After Mozart’s death, Salieri even instructed Mozart’s young son. In 2015, a short composition created jointly by Mozart, Salieri, and a third composer was unearthed from the archives of the Czech Museum of Music. The following year, a harpsichordist in Prague gave the work its first public performance in 230 years. Nadia Boulanger – A “hidden figure” in music Image by Wikipedia Image by Wikipedia Nadia Boulanger earned international fame as a conductor and teacher of musical composition. Born in 1887, she was the daughter of Ernest Boulanger, a renowned voice teacher at the Paris Conservatory. She studied at the conservatory with composers Charles-Marie Widor and Gabriel Fauré, then began a career teaching both private lessons and classes. At age 21, she received a second place honor in the Prix de Rome competition for a cantata she had composed. Boulanger’s sister, who died young, was also a talented composer. In fact, after her sister’s death, Boulanger deemed her own work as a composer to be of no further use and stopped creating entirely. However, she continued to both promote her sister’s work and to teach others. By the early 1920s, she was working at the American Conservatory at Fontainebleau. Boulanger went on to become the first female conductor to work with the New York Philharmonic and other American orchestras. She taught in the Washington, DC area during the Second World War. In 1949, she earned the position of director of the American Conservatory. Boulanger’s first American student was Aaron Copland, and she later taught Virgil Thomson, Leonard Bernstein, Philip Glass, and a host of other noted composers. She lived to be 92 years old, but never in her long life wrote a textbook outlining her ideas on music theory. Rather, she exerted a strong and nurturing personal influence on her pupils. She worked to give them an in-depth understanding of the technicalities of music while enhancing their individual gifts of composition and expression. Zoltán Kodály – The centrality of the voiceZoltán Kodály, one of the best-known 20th century Hungarian composers, was also a scholar of the folk music of his country. Along with his contemporary Béla Bartók, he became one of the foremost collectors of traditional Hungarian songs. Kodály’s own creative compositions include the massive Psalmus Hungaricus, first performed in 1923 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the joining of the cities Buda and Pest.

Kodály was also a contemporary of Boulanger and studied with Widor in Paris. He achieved renown for establishing the building blocks of what is today known as the Kodály Method, used by music teachers around the world. The Kodály Method works with the understanding that young children learn music best by doing, and that the body of traditional songs and dances of their own countries should form the core of their musical education, supplemented with the folk music of numerous other cultural traditions. Kodály’s system additionally puts great emphasis on the power and flexibility of the human voice as the first musical instrument. His method stresses singing as the best way to develop musical understanding and skill. Folk songs in the classroom offer numerous ways to build a strong and engaging music curriculum. Recent surveys by the National Association for Music Education (NAfME) show that its members are in near-unanimity in favor of teaching American heritage folk songs as a major part of the music curriculum. Zoltán Kodály, an early 20th-century Hungarian musicologist and music educator, held folk songs in the highest esteem as musical teaching tools. Today, teachers around the world make use of folk songs either through lessons based on the Kodály method or informally, as a means of enhancing the music curriculum and the study of other subjects. At the heart of the Kodály method is instruction in singing, movement, and playing musical instruments, with folk songs as the core content. This helps children to learn the traditional songs of their own cultures, and develop an appreciation for the richness of other cultures as well. Read on for some more interesting ways to use folk music in the classroom and beyond. Simple examples to inform music lessonsFolk songs, with their simple, repetitive musical phrasing, can serve as excellent means for teaching the basics of musical notation, harmony, tempo, rhythm, pitch, and artistic expressiveness. A wealth of classroom usesFolk songs also afford an opportunity to enrich STEM- and STEAM-focused learning. They can be used in physics classes to illustrate the science of sound, in art programs in conjunction with an activity involving making musical instruments, or as examples of various points in American and world history. With their catchy, easy-to-remember lyrics and rhythms, folk songs have become key components of popular repertoires for school bands, choral groups, and dance troupes. A springboard for creativityBecause they’re highly adaptable, folk songs can accompany any number of games or playground activities. They encourage movement and the physical joy inherent in music. Children can enhance the experience themselves by creating their own dances and games to accompany the songs. They can write pastiches that employ similar themes, or update the songs’ historical themes in amusing ways. A way to strengthen memory and memorization skillsTheir easy-to-recall rhythms and refrains make folk songs excellent tools for training the memory, as well as helping with recall. For instance, in adults with dementia and other cognitive disorders, the simple, familiar lyrics and melodies of traditional folk songs can bring about pleasant and soothing associations with their childhood. Refining children’s ear for languageFolk songs can help children to expand their vocabulary through the use of rare and unusual words. Students may not immediately understand some of the dated language in a song, but once they learn the new words, they will have added to their store of language, as well as to their ability to express themselves and communicate within a new framework of ideas. A number of researchers have drawn a strong connection between learning folk songs and learning the finer points of English grammar and syntax. Thanks to the memorable patterns of rhyme, rhythm, and repetition found in folk songs, this learning technique can be especially useful and meaningful for English language learners. Additionally, folk songs can help listeners to mirror and model correct word pronunciation and accent, while repeated singing or listening to a folk song will continue to reinforce the grammar and articulation of that particular song. A web of historical connectionsThrough folk songs, students learn not only about their musical heritage, but about the historical events that have shaped this heritage—and their own lives. These songs connect children to generations of people—in their culture and in others—who have come before them, and whose lives made the world what it is today. On its website, NAfME lists a number of American folk song genres that have developed over time, each deserving a closer look from teachers and students. These include African-American spirituals, Shaker tunes, songs of the Civil War, and work songs sung by railroad workers, seamen, and cowboys. Each can provide an intimate insight into what the lives of a wide range of Americans were like. A few historical examples Teachers who devote time to teaching some of the history behind folk songs have found that it often piques their students’ interest in learning more about the historical topics addressed. Children often enjoy hearing about the origin of a song and its history as played, sung, and danced to by various peoples over time.

Some teachers find that folk songs are a good fit with material geared to meeting state core educational standards. For example, many states’ official state songs are folk songs comprising multiple historical references, and as such are culturally, musically, and historically a part of every American child’s history. For example, “Yankee Doodle,” sung during the American Revolution by British and Colonial soldiers alike, is the state song of Connecticut. The official state gospel song of Oklahoma is “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” attributed to the former slave Wallace Willis, who, upon seeing Oklahoma’s Red River, is said to have been reminded of the Jordan River and the Bible story of the prophet Elijah being lifted into heaven in a chariot. The song “Shenandoah,” also known as “‘Cross the Wide Missouri,” is said to have originated with the French adventurers and fur traders, called voyageurs, who traveled along the Missouri River in the early days of the European push westward in North America. The song references a voyageur who fell in love with a Native American woman. It later was widely adopted by American sailors. Its mysterious references and simple, haunting melody have kept it at the center of the American folk song corpus for generations. Recordings of songs like “Shenandoah” can additionally serve to acquaint children with great singers in the American popular canon, such as Paul Robeson. In the 1930s, Robeson recorded a number of versions of the “Shenandoah” tune. Pete Seeger, Arlo Guthrie, Bruce Springsteen, and Tom Waits have also recorded their own versions. Comparison of the various versions of the song could be particularly instructive for older students studying vocal interpretation. |

Photo used under Creative Commons from Marina K Caprara

RSS Feed

RSS Feed