|

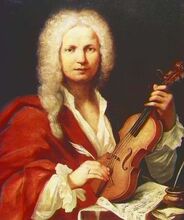

There is a variety of jobs for music teachers out there, from band and choir directors, to academy and university instructors, to vocal coaches, just to name a few. One thing all these types of music instructors have in common is the variety of professional organizations available to support them in broadening their networks and keeping their skills sharp. Here are a few of the best known and most respected. 1. MTNA – Close to 150 years of networking and advocacy  The Music Teachers National Association (MTNA) is one of the oldest professional groups for music teachers. Established in 1876, MTNA aims to make music study more accessible while highlighting the value of music to the general public. The organization’s 20,000+ members have access to extensive professional development programs, conduits to new performance opportunities for their students at every stage of proficiency, and numerous opportunities to meet fellow teachers, leaders in the field, and potential mentors. Members may also join active forums meant for specific group subsets, such as college professors or independent instructors. Membership includes a subscription to the organization’s flagship publication, American Music Teacher, as well as an online journal and access to a professional certification program. Members can additionally take advantage of discounted conference and programming fees. Though MTNA works in-depth at the local, state, and national levels, members must typically join at the state or local tier to participate in national programs. Any state chapter may request MTNA funding to pay for the commission of new work from a specific composer. From among these commissions, the national organization selects a recipient of its annual Distinguished Composer of the Year award. Also, the MTNA Foundation Fund accepts donations in support of programs that foster the study and teaching of music, as well as its appreciation, creation, and performance. 2. NAfME – A comprehensive teaching and learning resource Like MTNA, the National Association for Music Education, or NAfME, is more than a century old. Founded in 1907, the group has grown to become one of the largest arts-centered nonprofits in the world. NAfME’s focus is comprehensive, making it the sole organization of its kind devoted to every aspect of music teaching and learning. NAfME works to ensure that music students at every level have the resources and access to instruction with highly trained and responsive teachers while promoting rigorous standards for the teaching and learning of music. Like MTNA, NAfME works at multiple regional levels—local, state, and national—and has built a depth of experience and engagement among its members. Members have access to numerous professional development opportunities, and membership is open to teachers working in any type of organization and in any capacity. Teaching Music magazine is only one of NAfME’s publications aimed at working instructors. NAfME’s members share a concern for diversity, inclusion, and access in the music profession. The organization’s noteworthy advocacy efforts include its regular visits to lawmakers to educate them on the importance of music funding. NAfME’s wealth of online resources, such as webinars and other Internet-based development content, is especially useful as the coronavirus pandemic has reshaped the teaching and learning of all subjects. In addition to its value to professional instructors, NAfME offers several resources for students and parents, many of them freely available on the NAfME website. 3. ISME – Promoting music as everyone’s cultural heritage The International Society for Music Education, or ISME, is the leading global organization devoted to music education. It works to enhance the appreciation of the role of music in creating a vibrant, meaningful cultural life for all the world’s people. Affiliated with the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and its non-governmental organization, the International Music Council, ISME maintains a presence in more than 80 nations. A significant part of its mission focuses on championing the right of every person to an enriching and accessible music education, promoting wide-ranging scholarship in the field of music, and upholding the values of diversity and respect among all cultures. ISME traces its beginnings back to a UNESCO conference in 1953, which ended with participant representatives pledging to promote music education over the long term. Today, the organization, headquartered in Australia, continues to emphasize this mission, functioning as a global networking site for music teachers looking for ways to celebrate the diversity of the world’s music and preserve it as a valuable part of humanity’s cultural heritage. Members can join ISME under any of several categories that meet the needs of individuals, students, current and retired instructors, and groups. The 2020 World Conference was slated for Helsinki in August, but due to the global coronavirus pandemic, the event has been canceled. Even in the face of this unavoidable outcome, organizers are committed to publishing all previously accepted full papers as part of its conference proceedings and repurposing the content of accepted presentations as virtual educational opportunities.  Vivaldi | Image by Wikipedia Vivaldi | Image by Wikipedia Antonio Vivaldi, born in Venice in 1678, achieved fame during his lifetime as one of Europe’s greatest composers. His works have continued in popularity over the centuries—his “Four Seasons” and other richly textured concerti, as well as his operas, are still beloved by listeners all over the world. Vivaldi’s influence on the development of Baroque music, particularly on the emerging form of the concerto, cannot be overstated. Even scholars, however, often overlook how he opened doors for the participation of women in music. Here are a few facts about Vivaldi’s work with an extraordinary group of Venetian female musicians, and how they themselves achieved renown for their gifts in an age when few women and girls had such an opportunity. “The Red Priest” and the orphanageVivaldi worked with the church and orphanage of the Ospedale della Pietà in Venice sporadically from 1703 to 1740. An ordained priest nicknamed “Il Prete Rosso” (“The Red Priest”), most likely due to his vivid red hair, Vivaldi soon ceased to administer the sacraments and concentrated on his work as a composer and teacher. At the Ospedale, he served as a violin master and, later, a concert master. He also composed large numbers of works to be performed by one of the world’s most accomplished—and largely unknown—musical groups: a chorus and orchestra made up entirely of orphaned girls and young women. The long history of the orphanage The Ospedale was a creation of the Middle Ages. Founded by a 14th-century Franciscan priest as a charitable home for orphans, it took in both boys and girls who had lost their families to famine, plague, and other horrors that were common in the Europe of that time. It was attached to the Church of Santa Maria della Pietà, which also served as a public hospital. Throughout the Middle Ages and early modern period, such institutions—a combination hospital, orphanage, and musical conservatory—flourished in Venice. The Pietà was one of four major ospedali that made the city a must-visit musical destination until the fall of the Venetian Republic at the close of the 18th century. Marketing a music schoolThe Ospedale needed a continuous supply of generous patrons in order to feed, house, and clothe the increasing number of children within its walls. Its most creative—and best remembered—marketing effort involved establishing a girls’ choir, composed of its orphaned singers and musicians. The school would test each child at around age 9, to see if she had the needed flair for music. If a girl showed promise, the school made sure that she would have access to the finest musical education possible. (Researchers believe that many of the girls were not, in fact, orphans at all but the illegitimate children of noblemen, thus providing an additional explanation for the lavish expenditure of funds on a fine musical education.) Giving young women performers a voiceBeginning in the 1600s, the Ospedale’s girls’ choir performed in religious pageants to which the population of Venice was invited. By the following century, the fame of this orchestra was such that visitors from all over Europe traveled to Venice to hear, incidentally providing significant new revenue streams for the church and orphanage. Some of the young women performers became legendary, earning nicknames based on their talents. There was “Maria of the Angel’s Voice,” for example, and “Laura of the Violin.” But of the hundreds of girls who lived at the Ospedale, only a few dozen at a time had the talent necessary to become members of the orchestra and chorus. Vivaldi’s compositions for the schoolVivaldi became the most famous of all the renowned instructors of the Ospedale’s girls’ orchestra and chorus. He composed numerous cantatas, concertos, and sacred works specifically for his pupils to perform. One stellar example: He created “Gloria in D Major,” one of the finest compositions in the entire repertoire of sacred music, for the group. The girls sang this piece while situated high up in the top-most galleries of the church, where they would be concealed from the curious stares of tourists and the rough-and-tumble public. The fact that they were afforded an additional layer of protection by a latticed grille only served to enhance the atmosphere of lyrical majesty and mystery of the Gloria in performance. Vivaldi built the Gloria’s dozen small movements into a joyous praise song for God and God’s creation, with the music depicting moods from deep melancholy to bursts of happiness. A deeply moving novelIn 2014 American author Kimberly Cross Teter published a young adult novel, Isabella’s Libretto, a work of historical fiction based on the girls’ orchestra at the Ospedale. Isabella, the novel’s protagonist, is an abandoned infant taken in by the orphanage. She grows to be a gifted young cellist with dreams of one day performing a work that she hoped Vivaldi would create especially for her. But Isabella is also a free spirit and an annoyance to the Ospedale’s head nun, who sets out to tame her by requiring her to give cello lessons to a new pupil whose burned face testifies to her escape from the fire that killed her family. Isabella finds the grace within herself to rise to this challenge, even as the passing years school her in the bittersweet changes that adulthood brings. Her favorite teacher marries and leaves the orphanage, reminding Isabella that any girl who leaves is bound by the Pieta’s rules from ever performing music in public again. And Isabella herself must weigh her love for her art with her growing preoccupation with thoughts of a young man who seems to want to pursue her. Her struggles with her decision about which future she wants for herself make for compelling reading and will draw in empathetic readers. A resplendent picture bookStephen Costanza’s 2012 jewel-toned picture book Vivaldi and the Invisible Orchestra mines the same fascinating ground to tell the story of the Ospedale for younger readers. In this treatment, orphan girl Candida becomes a transcriber of Vivaldi’s emerging works, creating sheet music for the use of the performers in the “Invisible Orchestra”—so called because the female players performed from places of concealment. Candida’s value goes unappreciated, until the day a poem she composed finds its way into the sheet music, and her own creative gifts receive their due. In the author’s imagination, Candida’s sonnets provide Vivaldi with the inspiration he needs to produce his “Four Seasons,” perhaps his most famous and beloved work. The Ospedale todayThe Church of Santa Maria della Pietà still bears a nickname signifying it as “Vivaldi’s Church,” even though construction on its present building on the Riva degli Schiavoni was not finished until decades after his death. Today, the church stands adjacent to the Metropole Hotel, which was built up around a portion of the older Ospedale that had housed the music room.

The present church, constructed in the mid-18th century, recently underwent renovation after having fallen into disuse and disrepair and has reopened for concerts. Today, the church’s social welfare outreach program is still in operation, serving its community with early education programs for young children and parents in crisis. Additionally, a museum exhibiting some of the items associated with the centuries-old Ospedale is situated nearby. Teaching the basics of music doesn’t always have to take place in school. While formal music education programs are vital for giving children an appreciation of music as one of the quintessential human activities—and are certainly needed when children hope to pursue a musical career—parents and families can provide numerous informal opportunities to develop their children’s musical gifts. Music has an innate and immediate appeal to almost all children, so get creative and make it one of the focal points in your family life. The following suggestions, advocated by a variety of music teachers and family educators, can help point you in the right direction: Turn “trash” into treasure. Use ordinary items found around your home, office, or yard to produce interesting and captivating sounds. For example, you can start an entire percussion section with a few kitchen and garden tools: Pots and pans, lids, watering cans, metal or wooden spoons, empty jugs, unbreakable bowls, water glasses, and other items can produce a wide variety of tones. Try banging the sturdier items together, or beat them with spoons or ladles to make an impromptu drum set. Fill a series of glasses with different levels of water and gently strike them with a spoon. This latter activity is a wonderful chance to create your own STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts, and math) lesson, as you and your child see firsthand how the amount of water in a glass affects the speed at which sound waves travel and therefore the pitch of the resulting sound. Other items that can produce a variety of sounds for your child’s enjoyment include that bubble wrap you were about to throw away, pens and pencils, or even crumpled-up newspaper or wrapping paper. Get crafty.Making his or her own musical instruments together with adults can add to the fun of a child’s musical education. In addition, reusing items that you would have thrown away can help your family gain a greater appreciation of the need for recycling and purposeful spending. Numerous websites, put together by parents and teachers, offer lively selections of ideas and directions for making a rich array of simple instruments. An old box that may once have held tissue paper can be fitted with rubber bands to fashion a simple guitar. Plastic Easter eggs can be decorated and filled with dry rice, beans, or peas to become wonderful shaker instruments. A paper plate with jingle bells attached to it with string becomes a tambourine. And balloon skins stretched over the tops of a series of tin cans can become an exceptional set of drums. After you create your own instruments, practice them together. See how many sounds you can coax them to produce, and even try writing and performing a musical composition using only the instruments you have made. Experiment together while emphasizing to your child that improvisation and exploration are more important than “perfection.” Connect with real musical instruments.If you can buy or borrow real musical instruments, bring them into your home whenever possible. Young children are likely to be especially tactile, so let them experience what a drum set, a clarinet, or a flute feels like in their hands. A visit to a local museum that has a music exhibit, or to a music store or university music department, can also provide this experience. Investigate whether your community offers musical instrument lending libraries, which are designed to provide access to music education for all people, regardless of income. Such libraries are available in some locations in the United States, but residents of Canada are especially fortunate. Toronto, for example, recently initiated a musical instrument lending program through its public library system. Library patrons can check out violins, guitars, drums, and other instruments, free of charge. Listen together.Bring live and recorded music from as many cultures and time periods as possible into your home. Practice your listening skills, and see if you and your child can recognize the sounds of the different instruments in a composition. Encourage your child to catch the beat by clapping, tapping a foot, or creating a dance in time with the music. Hit the books.Bring home a variety of music-themed books, including picture storybook classics like Zin! Zin! Zin! A Violin, written by Lloyd Moss and illustrated by Marjorie Priceman; or The Philharmonic Gets Dressed by Karla Kuskin, with pictures by Marc Simont. Older children will also find plenty of music-themed fiction in titles such as Bud, Not Buddy by Christopher Paul Curtis and The Trumpet of the Swan by E. B. White. Your local bookstore or public library will likely offer all of these, and many others, as well as informational books about music and biographies of great musicians. Unite music and art.You can also look for coloring books that feature images of musical instruments or music performances. Additionally, a simple internet search using the keywords “musical instruments” and “coloring pages” will yield many free images to download and print for your child to decorate. Creating visual representations of musical instruments and concepts will provide a multi-sensory experience that can deepen your child’s connection to the related art of music.

At Music Training Center (MTC) in Philadelphia, children can take lessons in music and voice training. They can also participate in an a cappella vocal ensemble, Rock Band classes, or a number of high-quality musical theater productions. Over the years, Music Training Center has nurtured the talents of a number of promising young musicians and performers. The musical theater component is one of the organization’s signature programs. Kids in the upper elementary, middle school, and early high school grades can participate in its Main Stage musical production. Younger kids work on their own Junior Stage and Mini Stage productions. Popular musicals serve as an excellent way to engage kids with learning the basics of musical theater stagecraft. Experts in the performing arts have noted musical theater’s ability to develop a wide range of essential talents and skills in children who are considering making any branch of acting or performing a lifelong career. Further, musical theater training can lay the foundation for the kind of self-confidence, physical and mental stamina and agility, and personal presentation skills that will enhance a young person’s performance in any other type of career later on. There are many reasons to encourage your child to participate in musical theater. Here are four: 1. Musical theater programs are available throughout the countryThe MTC program is only one of many across the country that focus, either year-round or as a special summer experience, on the wealth of benefits that participation in a musical theater production can provide for children. The Performers Theatre Workshop in New Jersey, the Music Institute of Chicago, and San Francisco Children’s Musical Theater are only a few more examples of organizations that offer this kind of vibrant and engaging—and potentially life-changing—programming. 2. Musical theater helps teach movement, communication, and confidence.For example, kids who participate in musical theater training learn a whole set of movement skills. These skills can improve coordination, kinetic awareness, and overall fitness. In addition, training the voice to perform songs in a musical theater production tends to strengthen the vocal chords. They also benefit the performer’s overall voice presentation. This is a helpful tool for leaders and communicators in any field. Experts in teaching musical theater additionally point out that confidence is among the main takeaways from participation for many kids. Musical theater can take performers far beyond their familiar comfort zones. A student who primarily views herself as an actor might be asked to sing in a particular production. Another who thinks of himself only as a dancer might be called on to learn and speak lines of dialogue to convey an emotional experience. These activities might at first give young performers a case of nerves. Ultimately, however, this type of multifaceted training can open doors onto new ideas, build new skills, and create a sense of accomplishment in ways that stay meaningful over a lifetime. 3. Musical theater boosts self-esteem. One dissertation-related study, published in 2017 under the auspices of Concordia University-Portland, found that music and theater studies, individually, offer enormous potential. They can help middle school students develop their self-esteem and their scholastic achievement. The study goes even further by exploring the ways in which the combination of the two subjects in musical theater can lift up middle school students’ sense of self-worth and facilitate their achievement in a number of ways. In this particular study, about a dozen suburban private school students in Minnesota took part in staging a musical theater event. The researcher used direct observation, interviews, school records, and Likert scale surveys to gauge the degree to which the students engaged in a positive or negative way with the experience. The study concluded that if a student came into the production with already-high levels of self-esteem, he or she did not experience an additional boost of self-esteem from participation. On the other hand, if a student had a lower level of self-esteem before the production, he or she was more likely to develop more openness to being flexible and taking on novel tasks during the course of the production. These students also showed increased comfort with the process of change during the production. 4. Musical theater is fun!One remaining important aspect of performing in musical theater: it's fun. Kids of all ages enjoy meeting familiar or intriguing characters from movies, books, or TV shows translated onto the stage.

When they take on the personas of these characters themselves, they can find creative new ways to express themselves. They can also deepen their awareness of their own emotions and let their imaginations take them on new adventures. Can the study of music, or a program of music therapy, help children struggling with emotional or behavioral disorders? A growing number of experts say it can. Emotional disorders in children and adolescents can have a number of negative or potentially dangerous consequences. These can include a chronic lack of academic success, aggression against peers, isolation from others, substance abuse, running away from home, and even violence against oneself or others. Children with emotional and behavioral disorders may have extremely limited functioning in one or more areas. This can prevent them from engaging in a healthy way with their families, schools, or communities. A comprehensive plan of general psychological or psychiatric therapy is likely to be the lynchpin of any successful program to treat these conditions. However, such a plan can be enhanced considerably by the incorporation of music. Music can help in a variety of ways.Music therapy can improve a child’s self-image, and can help him or her develop much-needed self-esteem and a clearer and stronger personal identity. For any child or teen who has experienced abuse, this type of therapy has the potential to promote positive new attitudes about themselves and their worth. Recent research has demonstrated the capacity of music therapy to help in several specific ways in working with children with emotional disorders. These involve the regulation of the child’s own emotions, developing communication skills, and addressing challenges with social functioning. Music therapy has proven extremely useful in decreasing children’s levels of anxiety and developing their ability to be emotionally responsive. Young people who have difficulty controlling their impulsivity have also been helped by music therapy. In fact, a carefully structured and appropriately repetitive series of experiences that engage multiple senses, presented within a context of acceptance and support, can be of immense value in a variety of clinical settings. Some research has even suggested that the use of music can even produce a sense of relaxation that leads to improved performance on a range of assessment metrics. Music fosters positive social interactions. The use of music in therapy provides young people with a topic of conversation. This makes it an excellent starting point for establishing comfort within a social group and for fostering healthy self-expression. Music can help a child experiencing social challenges to gain greater awareness of the presence and feelings of others. It can also facilitate greater levels of cooperation with peers and adults. Children who participate in music therapy have also shown a decreased level of disruptive incidents as reported in psychological studies. Music’s value as a social harmonizer in the general classroom becomes especially important when working with children with emotional and behavioral dysfunction. This is because it can help establish a positive atmosphere and encourage the development of cooperative skills. Experts point out that, once such a foundation is laid, it can be used to build a child’s social skills out still farther. Music teaches new skills and builds confidence.At least one researcher in this field has reported that a series of carefully-structured experiences with music, supported by targeted and easily understood reinforcement, enabled children labeled “delinquent” to gain a positive self-concept. In one study, a 12-year-old with significant behavioral issues who learned to play the piano gained constructive new communication skills, made measurably fewer negative statements about themselves, and showed notable motivation to continue learning music. Music improves verbal and nonverbal communication skills.Songwriting, or communicating through the lyrics of a song, can offer a non-threatening means of communication. For many children with emotional difficulties, speaking through lyrics makes self-expression much easier. Music also has an appeal beyond the realm of the verbal. This makes it an ideal tool for connecting with young people who may be hard to reach, who may themselves be non-verbal, or who may feel threatened by engaging in direct, one-to-one conversation. One perhaps underappreciated benefit of music therapy as a non-verbal means of communication is that it is nonthreatening. When listening to music, a child may feel they have a safe space in which to engage with emotional issues that might otherwise feel too complex or unsettling to confront. A skilled music therapy practitioner can even tailor-make a program to assist a child in coping with overwhelming emotions such as grief, anger, or trauma. Experts point out that for many young people with serious emotional issues, music can become both an outlet for expression as well as a core therapeutic component. For many children in this population, it serves as an effective way for them to establish communication channels with therapists, parents, teachers, and peers. Music has significant short-term gains.In a study based in Northern Ireland, a cohort of some 250 school-age children and teens exhibiting a range of emotional and behavioral challenges were divided into two groups. One received treatment via music therapy. The other received the current standard of care. More than half the total cohort had exhibited significant levels of anxiety.

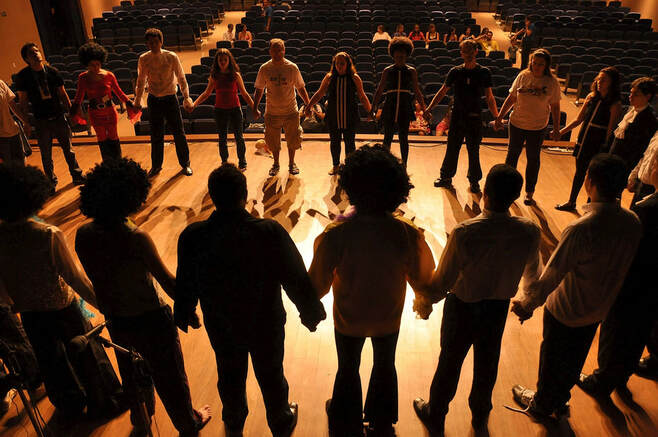

The young people who participated in the music therapy program explored improvisation and music creation through singing, movement, and playing musical instruments. The therapist worked with the youth for half an hour at a time, for 12 weeks total. Through these sessions, the therapist was able to contextualize the experience and provide a supportive atmosphere with the ultimate goal of improving communication and social skills. The study showed that, in the short term, the group that received music therapy showed decreased levels of depression and increased feelings of self-esteem. Communication skills appeared unchanged. Longer follow-up studies showed that the improvement in other areas eventually dropped off. The conclusion: at least on a short-term basis, music therapy may be helpful for young people with a range of behavioral and emotional challenges. Zoltán Kodály ranks among the foremost music educators of all time. He was born in what is now Hungary in 1882, and, well before his death in 1967, had earned an international reputation as a composer of highly original pieces, a scholar of folk music, and the originator of the method of music instruction that continues to bear his name. The Kodály Method has become widely known among music educators for its dynamic, interactive, and movement-oriented approach to instruction for children. It incorporates a set of proven techniques that foster the unfolding of a child’s natural gift for musicianship. The approach, which focuses on creativity and expressiveness, has demonstrated its relationship to the traditional ear-training method. During Kodály’s lifetime, his influence was felt throughout Europe and the world as an instructor who taught numerous teachers, and his method continues to be popular today. A young composer and teacher finds his vocation.In his youth, Kodály studied the piano, cello, and violin. When he was in his teens, his school orchestra performed several of his compositions. In 1900, he enrolled at the University of Sciences, located in Budapest, and became a student of contemporary languages and philosophy. He went on to study composition at Budapest University, but before graduating, he spent a year criss-crossing Hungary on a search for sources of traditional folk songs. He then centered his university thesis on the structural properties of Hungarian folk songs. Shortly after graduating in 1907, Kodály accepted a position in Budapest teaching the theory and composition of music at the Franz Liszt Academy of Music. He would remain on the school’s faculty for 34 years. Even after retiring, he returned to the school in 1945 to serve as a director. His dedication was driven by a desire to preserve his country’s musical culture, particularly in light of the unrest that characterized its political scene in his time. Before he entered into his duties at the Liszt Academy, Kodály met fellow Hungarian composer and folk music collector Béla Bartók. Together they published, over a span of 15 years, a folk song series based on their research. The series became the core of Hungary’s authoritative corpus of popular music. A 20th century master of styles.Kodály’s own style as a composer was anchored in the folk music that he loved and had a richly Romantic tone, while incorporating classical, modernist, and impressionistic techniques, as well. His best-known works include a concerto for orchestra, chamber pieces, a comic opera, groups of Hungarian dances, and the 1923 work Psalmus Hungaricus, which was created to honor the 50-year anniversary of the fusion of Buda and Pest into a single city. The piece brought him international fame and conferred upon him the mantle of musical spokesman for the culture of his country. As both a scholarly writer and musician, Kodály in his later years penned numerous books and articles on Hungarian folk songs. An evolving method.One story, perhaps apocryphal, has it that Kodály was so disappointed when he heard a group of schoolchildren perform a traditional song that he decided to improve the state of Hungarian music instruction himself. Kodály put nearly as much emphasis on developing his music education program as on his own creative works of composition. His interest in the issue of music teaching was intense, and he produced a variety of educational publications designed to expand the horizons of teachers. Kodály thought that music was among the vital subjects that should be required in all systems of primary instruction. He further stipulated that it be presented in a sequential framework, with one step logically leading to the next. He believed that students should enjoy learning music, that the human voice is the premier musical instrument, and that the most accessible teaching method incorporates folk songs in a child’s original language. Kodály himself was primarily the originator of his eponymous method, generating numerous ideas and principles that now form the basis of its core teachings, as used in classrooms today. However, it was left to the Hungarian teachers that he trained and inspired to fully develop it over time, often under his direct guidance. The Kodály Method serves as a comprehensive system of training musicians in the reading and writing of musical notation, as well as the acquisition of basic skills. In doing so, it draws upon proven techniques in the field of music instruction. It is also in itself a philosophy of musical development that emphasizes the experiences of each learner. The importance of the human voice. One of the basic principles of the method is singing, which Kodály himself viewed as the core of his system. The Kodály Method stresses that, first, a child should learn to love music for the sheer fact that it is a sound made by other human beings, and one that makes life richer and happier. Teachers of the method also emphasize the human voice as the one musical instrument accessible to most people around the world as a common means of expression. One reason why singing has such a central role in the method is the idea that the music one creates by oneself is better retained and provides a greater feeling of pride and personal accomplishment. The Kodály Method therefore places singing—and reading music—ahead of any sort of training on an instrument. Kodály also believed that singing was the best means of training the inner musical ear. The content of any classroom based on the Kodály Method will consist largely of folk songs from a child’s own heritage, as well as those of other cultures. Classic childhood rhymes and games will also be included, as will pieces of great music produced in any time and place. Continuing the work. Since 2005, the Liszt Academy has hosted the Kodály Institute, which provides advanced-level music education training for teachers, based on the Kodály Method. The institute works as the guiding force for the entire set of music instruction programs of the academy. In addition to its teacher-training programs, the institute offers the International Kodály Seminar every two years. Participation in the seminar is open to music teachers around the world and coincides with an international festival of music. The next seminar is scheduled to take place in July 2019. For more information, visit Kodaly.hu.

Folk songs in the classroom offer numerous ways to build a strong and engaging music curriculum. Recent surveys by the National Association for Music Education (NAfME) show that its members are in near-unanimity in favor of teaching American heritage folk songs as a major part of the music curriculum. Zoltán Kodály, an early 20th-century Hungarian musicologist and music educator, held folk songs in the highest esteem as musical teaching tools. Today, teachers around the world make use of folk songs either through lessons based on the Kodály method or informally, as a means of enhancing the music curriculum and the study of other subjects. At the heart of the Kodály method is instruction in singing, movement, and playing musical instruments, with folk songs as the core content. This helps children to learn the traditional songs of their own cultures, and develop an appreciation for the richness of other cultures as well. Read on for some more interesting ways to use folk music in the classroom and beyond. Simple examples to inform music lessonsFolk songs, with their simple, repetitive musical phrasing, can serve as excellent means for teaching the basics of musical notation, harmony, tempo, rhythm, pitch, and artistic expressiveness. A wealth of classroom usesFolk songs also afford an opportunity to enrich STEM- and STEAM-focused learning. They can be used in physics classes to illustrate the science of sound, in art programs in conjunction with an activity involving making musical instruments, or as examples of various points in American and world history. With their catchy, easy-to-remember lyrics and rhythms, folk songs have become key components of popular repertoires for school bands, choral groups, and dance troupes. A springboard for creativityBecause they’re highly adaptable, folk songs can accompany any number of games or playground activities. They encourage movement and the physical joy inherent in music. Children can enhance the experience themselves by creating their own dances and games to accompany the songs. They can write pastiches that employ similar themes, or update the songs’ historical themes in amusing ways. A way to strengthen memory and memorization skillsTheir easy-to-recall rhythms and refrains make folk songs excellent tools for training the memory, as well as helping with recall. For instance, in adults with dementia and other cognitive disorders, the simple, familiar lyrics and melodies of traditional folk songs can bring about pleasant and soothing associations with their childhood. Refining children’s ear for languageFolk songs can help children to expand their vocabulary through the use of rare and unusual words. Students may not immediately understand some of the dated language in a song, but once they learn the new words, they will have added to their store of language, as well as to their ability to express themselves and communicate within a new framework of ideas. A number of researchers have drawn a strong connection between learning folk songs and learning the finer points of English grammar and syntax. Thanks to the memorable patterns of rhyme, rhythm, and repetition found in folk songs, this learning technique can be especially useful and meaningful for English language learners. Additionally, folk songs can help listeners to mirror and model correct word pronunciation and accent, while repeated singing or listening to a folk song will continue to reinforce the grammar and articulation of that particular song. A web of historical connectionsThrough folk songs, students learn not only about their musical heritage, but about the historical events that have shaped this heritage—and their own lives. These songs connect children to generations of people—in their culture and in others—who have come before them, and whose lives made the world what it is today. On its website, NAfME lists a number of American folk song genres that have developed over time, each deserving a closer look from teachers and students. These include African-American spirituals, Shaker tunes, songs of the Civil War, and work songs sung by railroad workers, seamen, and cowboys. Each can provide an intimate insight into what the lives of a wide range of Americans were like. A few historical examples Teachers who devote time to teaching some of the history behind folk songs have found that it often piques their students’ interest in learning more about the historical topics addressed. Children often enjoy hearing about the origin of a song and its history as played, sung, and danced to by various peoples over time.

Some teachers find that folk songs are a good fit with material geared to meeting state core educational standards. For example, many states’ official state songs are folk songs comprising multiple historical references, and as such are culturally, musically, and historically a part of every American child’s history. For example, “Yankee Doodle,” sung during the American Revolution by British and Colonial soldiers alike, is the state song of Connecticut. The official state gospel song of Oklahoma is “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” attributed to the former slave Wallace Willis, who, upon seeing Oklahoma’s Red River, is said to have been reminded of the Jordan River and the Bible story of the prophet Elijah being lifted into heaven in a chariot. The song “Shenandoah,” also known as “‘Cross the Wide Missouri,” is said to have originated with the French adventurers and fur traders, called voyageurs, who traveled along the Missouri River in the early days of the European push westward in North America. The song references a voyageur who fell in love with a Native American woman. It later was widely adopted by American sailors. Its mysterious references and simple, haunting melody have kept it at the center of the American folk song corpus for generations. Recordings of songs like “Shenandoah” can additionally serve to acquaint children with great singers in the American popular canon, such as Paul Robeson. In the 1930s, Robeson recorded a number of versions of the “Shenandoah” tune. Pete Seeger, Arlo Guthrie, Bruce Springsteen, and Tom Waits have also recorded their own versions. Comparison of the various versions of the song could be particularly instructive for older students studying vocal interpretation. The study of an instrument is a long-term commitment. Students will need to feel comfortable with their choice and dedicated to getting the most out of their studies. With hard work, focus, and diligence, however, learning to play an instrument can be a way to enrich a child’s life well into adulthood. The following seven tips can help parents, educators, and children identify the instrument that will be the best and most enjoyable fit. 1. Consider the child's age and development.First, consider the child’s age. For particularly young children, consider the physical and developmental demands of each instrument. Children of this age may not have the physical strength, dexterity, or muscle fluency to manage certain instruments. 2. Consider the piano and the violin, particularly for younger children.  Expert teachers typically recommend the violin and the piano for children under 6 years of age. Both of these instruments serve as excellent building blocks for learning music theory and practice. They also assist with learning to play additional instruments. The Suzuki Violin Method is one of the teaching practices that focuses specifically on the qualities of the violin as a young beginner’s instrument. Learning violin is made easier for younger children because the instrument can be fashioned in very small sizes. This makes it simpler and more intuitive for a child this age to manage fluidly and naturally. The violin is also an excellent choice of instrument for teaching young music students to play in tune. Another advantage is that the act of bowing provides a kinetic manner through which students can learn the concept of musical phrasing. And, because the violin has no keys or frets, a young player can concentrate completely on the sounds he or she is creating. The piano offers its own plusses as a first instrument. A child learning to play the piano picks up foundational skills of musicianship by becoming proficient in harmony and melody at one and the same time. Piano students gain experiential knowledge that will help them to better understand music theory. 3. Consider the child’s physical abilities and limitations.An instrument’s design and its fit with a child’s physicality is also an important consideration. If a child’s hands are relatively small, for example, he or she may not have the finger span to become an accomplished pianist or a player of a larger stringed instrument. For woodwinds and brass instruments, make sure that the embouchure—the place where the child places his or her mouth to produce sound—is a good fit. Keep in mind that some students take time to learn the best way to address this. The oboe has a double read mouthpiece and the French horn has a slender tube mouthpiece. As a result, these instruments present particular challenges regarding their fit against a player’s mouth. For children who need orthodontic help, it can be better to select a stringed or percussion instrument. This is because blowing through any sort of embouchure may be uncomfortable or even painful. 4. Consider which instruments the child enjoys listening to.Sound is an important quality as well. A child should enjoy the sound her instrument makes. Otherwise, he or she may be reluctant to continue practicing and playing it. Experts point out that it is unrealistic to believe that, over time, a child will come to like the sound of an instrument he or she dislikes. Such a child may, instead, neglect lessons and resent practicing. This is particularly important for parents to remember, because band directors sometimes encourage children to take on specific, less-popular instruments simply because one is needed in the ensemble. 5. Consider the child's temperament.A child’s personality is another good indicator of the best instrument to select. For example, an outgoing child who enjoys being the center of attention will likely gravitate to an instrument that offers greater potential for front-of-the-band performance and solos. These instruments include the flute, saxophone, and trumpet. All are made to carry a central melodic line, rather than to play supporting roles. 6. Consider the social implications of the selected instrument.One factor sometimes swept aside by adults can have a big impact on children. This factor is the social image of an instrument, and what that says, by implication, to peers about a child’s own image and personality. Many children gravitate toward the instrument they perceive as having the most status among their peers. Unfortunately, that instrument may not be the best fit. Adults should encourage each child to take a fresh look at the instrument that actually seems best for him or her. 7. Consider your budget as well as any maintenance commitments.Practical issues of cost and maintenance will also be on most parents’ lists when choosing an instrument. Take some time to go over a realistic timetable of maintenance with a child’s music teacher. A piano, for example, is one of the most expensive instruments, and needs to be tuned twice annually by a professional.

Remember that many music vendors offer monthly payment programs. A trial rental may also be a good option until a child is certain that he or she really likes an instrument. Some schools will facilitate free long-term loans of instruments for their band members. It may also be worthwhile to explore options provided by nonprofit groups. For example, Hungry for Music supplies children in financial need with donated and carefully refurbished instruments. Experts point out that nothing encourages children to love reading more than when a parent sets the example. Children who see the adults in their lives taking time to read for pleasure are more likely to become enthusiastic readers themselves. So why not do the same thing for classical music? One way to start children off with a love of music is to model exactly what that looks like: Play musical games together, dance and sing as part of regular family activities, attend concerts, and enjoy recordings of great music together. But how can a parent demonstrate a love for classical music if he or she hasn’t had the opportunity to develop a taste for it? Fortunately, a number of popular books—all written for interested adult laypeople by experts in the field—are available. The following list represents a sampling of fascinating books that can inspire a love of serious music while providing an enjoyable, educational read. 1. Experience the wonderYear of Wonder: Classical Music to Enjoy Day by Day by Clemency Burton-Hill offers simple, one-page summaries—each tied to a specific day of the calendar year—of the delights to be found in 365 different pieces of music. The 2018 book, published by Harper, brings this expert musicologist and media personality’s extensive knowledge of the subject within easy reach of anyone who has time to read one page each day. The book offers a fun way to browse through Burton-Hill’s carefully curated selections as she provides fascinating snippets of information about each work, its composer, and its historical context. While it makes a delightful browsing book, Year of Wonder can also be used as a personal tutor through a year of discoveries in classical music. Readers can look for online or hard-copy recordings of each work, making for an enriching multimedia listening and learning experience. 2. Glimpse fascinating livesThe Indispensable Composers: A Personal Guide, written by Anthony Tommasini and published by Penguin Press, is another 2018 title that provides a wide-ranging journey through the history of great music and exactly how its creators made it. Tommasini serves as the New York Times’ head music critic, and his encyclopedic knowledge of his subject is on vivid display in this book. His assessment of each composer is easy-to-understand, free of jargon, and completely accessible, and is often accompanied by fascinating anecdotes and discussions of other cultural figures and of the author’s personal experiences in the world of music. Even those who are unfamiliar with the ways in which, for example, Beethoven’s concertos or Arnold Schoenberg’s twelve-tone technique revolutionized music will be able to grasp the significance of these and other big moments in the history of the classical music genre. 3. Catch the enthusiasmA Mad Love: An Introduction to Opera by Vivien Schweitzer, published in 2018 by Basic Books, brings the world of opera down to earth for even the most skeptical contemporary reader. Schweitzer, a former New York Times opera and music critic and pianist, offers readers a vivid romp through opera’s history and development, checking in on the most noted composers, performers, and performances along the way. This lively book should dispel any stereotypes about opera being dull or beyond the comprehension of everyday people. Schweitzer ranges from the first opera known to have been composed—the early 17th century L’Orfeo by Claudio Monteverdi—through great Romantic era pieces like Carmen by Georges Bizet to contemporary works by composers like Philip Glass. The author provides us with riveting stories of the high—and low—moments in opera’s dramatic history, including the initial hostility of audiences toward Gioachino Rossini’s now-classic The Barber of Seville, and the rising and falling critical reputations of composers such as the near-contemporaries Richard Wagner and Giuseppe Verdi, bringing considerable wit and humor to the task. 4. Take a tour with an iconic guideIn 1984, beloved radio personality Karl Haas published Inside Music: How to Understand, Listen to, and Enjoy Good Music. Haas, who died in 2005 at age 91, had become an informal instructor in classical music for people all over the world through his program called Adventures in Good Music, broadcast by numerous public radio stations. Inside Music brings Haas’ distinctive blend of erudition and lively, pun-filled sense of humor to the fore, providing a friendly guided tour through the history and composition of great works. The book has been through multiple editions and remains in print under the Anchor imprint. Generations of readers have found it an indispensable first survey of its subject. 5. Enjoy a master classThe Lives of the Great Composers by Harold Schonberg, originally published in 1970, is another older classic widely read and loved by amateur and professional students of music alike. Still available in an updated edition published by W. W. Norton & Company, the book offers detailed but easily digestible biographical portraits of composers from the Baroque era to the minimalists, tonalists, and experimentalists of the 20th century.

The author additionally covers the lives and contributions of female composers such as Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel, the sister of Felix Mendelssohn. This makes a welcome addition to our expanding knowledge of composers who have remained underappreciated for generations due to their gender. Schonberg, who died in 2003, was another New York Times music critic, and the first person ever to earn a Pulitzer Prize for music criticism. A 2016 piece in The Atlantic echoed numerous other recent articles noting that increasing focus on academic standards and testing in schools has led to a declining focus on character building and empathy. While parents and teachers are becoming more aware and concerned about this problem, music offers many solutions. Here are seven ways music education can promote social harmony: 1. Developing compassionate citizens.Renowned music educator Dr. Shinichi Suzuki, who originated the Suzuki method, understood that learning to play a musical instrument could be a significant part of learning to develop into a caring human being and a good citizen. In fact, many music teachers view the Suzuki method as being in a class by itself for this very reason. Experienced teachers also note that the same skills acquired when children study music lead to the development of positive character traits such as tolerance, respect, and a sense of perspective. Working together to study and perform a piece of music fosters a sense of common purpose and encourages collaboration with other people who come from a variety of backgrounds and possess a range of viewpoints. 2. Getting people in touch with their emotions.In their book Music Matters: A Philosophy of Music Education, published by Oxford University Press, David Elliott and Marissa Silvermann discuss the emotional component in music. This is a perennial topic in any discussion of music, going back to the days of the ancient Greeks. Both Plato and Aristotle commented on the ability of music to evoke either positive or negative emotions in listeners. Neurologists and psychologists focused on the power of music agree. In fact, sophisticated new research studies show how musical notes and chords can produce corresponding emotional states in listeners. 3. Counteracting bullying.In fact, a 2015 article in Psychology Today magazine even suggests some music is a possible antidote to extreme antisocial behaviors such as bullying and bigotry. The article points out that learning to play a musical instrument beyond the level of bare technical proficiency draws on a host of emotional skills and sensitivities. In order to produce the most pleasing sequences of sounds and reach the hearts of audience members, a player needs a certain level of emotional maturity and expressiveness. A range of talented musicians have opined that music can deepen and broaden an individual’s perspective. As a result, he or she can grow beyond early prejudices and begin to view other people with greater comprehension and appreciation. For example, the late jazz musician Paul Horn was once quoted as saying that music is an extremely useful way to bring people together in greater peace and mutual understanding, easing the burden of communicating across personalities and cultures. Numerous other musicians have specifically noted music’s power to overcome even the strongest racial and cultural prejudices. 4. Reducing violence.A group made up of musicians, producers, and others based at the University of California, Los Angeles created a collective performance space for the expression of a wide variety of world music instruments and genres. They called their collective Westwood Village Entertainment Group. It has worked to facilitate a welcoming environment for a diverse group of musicians, performers, and audiences. The idea emerged out of one young ethnomusicologist’s experiences growing up in a crime-filled neighborhood in New Jersey. The young man found escape through learning to play African drums. Now, because of WVEG, he and his fellow musicians hope to foster a sense of community and welcome. 5. Reminding listeners of relevant events or eras.The canon of popular music is filled with deeply moving, inspirational pieces that seek to heal the rifts and prejudicial attitudes that arise between people. Examples include Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On?” as well as Curtis Mayfield’s “We Got to Have Peace” and the classic hymn of the Civil Rights era, “We Shall Overcome.” 6. Reducing bias and promoting empathy.One study, published in Psychology of Music, centered on a social experiment with elementary school children in Portugal. Their community is composed of lighter-skinned people descended from families with long histories in the European country as well as darker-skinned people whose heritage lies in the African island nation of Cape Verde. Over a period of several months, the researchers introduced one group of young students to songs from Cape Verde in addition to their regular lessons in European Portuguese music. A control group did not receive exposure to the Cape Verdean songs. Before the study, all of the children surveyed displayed a moderate amount of bias against darker-skinned individuals. By the conclusion of the study, however, the children who had been exposed to the music of Cape Verde demonstrated significantly lower levels of such prejudice. The control group showed no change in their negative attitudes. The researchers in this study theorized that, for the children involved, learning to like the music of Cape Verde translated over into learning to like the other children whose families came from Cape Verde. This aligns with a principle identified in psychological research. The idea is that a feeling of similarity or having common interests with another person tends to increase empathy for that person. The researchers further theorized that songs may be particularly valuable tools for fostering feelings of commonality and similarity, and thus of empathy. 7. Strengthening interpersonal relationships.A 2015 article in Music Educators Journal makes a similar point. Its authors posit that the collaborative experience of making music with others involves activities such as synchronization, group problem-solving, imitation, and call-and-response.

All these activities tend to have a positive influence on interpersonal relationships and on individuals’ abilities to work successfully in groups, and thus, on the development of empathy. According to experts, the themes of music are the themes of human life itself. Therefore, learning to make music makes us more human. |

Photo used under Creative Commons from Marina K Caprara

RSS Feed

RSS Feed