|

The blues puts into music what we all feel when it seems like we just can’t go on: lost jobs, friends, love, and dreams. But the very music that was made to express the depths of despair can, by its very artistry, lift us up again. The blues is also cathartic. It’s about overcoming obstacles. The blues was born out of African American history. It traces its origins to plantation slavery, through the toiling oppression of the Jim Crow era, and into the days of escape to a completely new world during the Great Migration. Ultimately, the blues has its roots in African American work songs and chants, spirituals, and rural “field hollers.” It came to early maturity in the Mississippi River Delta around New Orleans, growing up alongside jazz, before branching out west, east, north, and finally around the world. Here is a look at three of the many distinctive styles of the blues that developed in the United States throughout the mid-20th century, along with portraits of three of their leading creators. Meade “Lux” Lewis’ piano-pounding boogie-woogieThe boogie-woogie blues, heavy on rhythm and percussion and with a varied and unpredictable style, was the first and only type of piano music born directly out of the blues. In boogie-woogie, the right hand’s riffs play off against the left hand’s ostinato drive. Boogie-woogie flourished from the beginning of the 1920s until the end of World War II in 1945. The word “boogie” referred to a house rent party among people living in tenements in big cities with large African American populations. Rent parties opened up new ways to socialize while helping to pay their rent during hard economic times. The ultimate source of the boogie-woogie style may have been the logging camps, gin mills, and other labor groups offering some of the few means of good employment available to Black workers in the early 20th century. Just as “field hollers” and hawking shout-outs were earlier, boogie-woogie rhythms were highly personalized. Meade “Lux” Lewis (1905-1964) was one of the driving forces behind the popularity of boogie-woogie and its rolling beat. Born in Chicago, “Lux” started out playing violin, but turned to piano in the ‘20s. In 1927, he recorded the enormously popular “Honky Tonk Train Blues,” a pull-out-all-the-stops cascade of sound, and a now-legendary piece in the blues catalog. His musically sophisticated tunes also included “Whistlin’ Blues,” “Bear Cat Crawl,” and “Low Down Dog.” By the mid-1930s, the song had fallen into obscurity, until Lewis was rediscovered while working in a car wash. Producer John Hammond reissued the song, and Lewis gained a brief nationwide fame before boogie-woogie faded from the charts. In the late 1930s, Lewis joined fellow boogie-woogie masters Albert Ammons and Pete Johnson in a series of star-studded “six-handed” performances, and his three film appearances include an uncredited role as a bar piano player in the 1946 Jimmy Stewart classic It’s a Wonderful Life. Lewis died tragically in a car accident in Minneapolis when he was only 58. Louis Jordan’s jumping saxJump blues was a highly danceable mix that blended blues, jazz, swing, and boogie-woogie. The style originated—just as boogie-woogie did—amid hard economic times, although jump blues was reaching widespread popularity as boogie-woogie was winding down. During and after World War II, full swing bands were too expensive, so bands scaled down to simply a rhythm section and often a single soloist. The smaller size enabled musicians to concentrate on innovating with a more fast-paced and uninhibited “jump” sound. Louis Jordan (1908-1975), saxophonist, singer, movie performer, and bandleader of the Tympany Five, as well as an accomplished all-around entertainer known as the “King of the Jukebox,” is credited as the originator of this style. Jordan’s talent shone on numbers like “Jumpin’ at the Jubilee,” “Is You Is Or Is You Ain’t My Baby,” and “Caledonia,” and he became one of the most popular and successful Black artists of the 1940s and ‘50s. The vibrant, bouncy rhythms and clever lyrics of his songs—not to mention his high-energy, engaging stage presence—made the Arkansas-born Jordan wildly popular with audiences of all backgrounds. In fact, he is one of the few African American artists to gain widespread acceptance among white fans of his era. He had at least four million-selling hit songs over his career, and in earnings and name recognition ranked near Duke Ellington and Count Basie among African American musicians of his day. Numerous critics consider “Caledonia” (1945) to be the immediate ancestor of rock and roll. Jordan is also often credited as the father of rhythm and blues and rap. The growth of Chicago blues followed right along with the growth of the Black population of major northern cities. During the Great Migration that began in the final years of World War I and that continued into the 1970s, some 6 million African Americans picked up everything and moved from the rural, segregated South to the industrial and at least nominally more accepting cities of New York, Philadelphia, Detroit, and Chicago. And they took their music with them. Alongside New Orleans and Austin, Texas, Chicago remains one of the three key cities involved in the development of the blues art form. The blues musicians who moved north continued the evolution of the sound as it played out in people’s everyday lives on street corners, in open-air markets, at rent parties, and a host of other community events. Buddy Guy’s electrified ChicagoThe rough-and-tumble action along the city’s streets was further inflected by emerging technologies that amped it up with an electric beat, forming the nexus of a new kind of club atmosphere. Chicago’s South Side saw numerous Black-focused blues clubs spring up, including big names such as Smoke Daddy, Ruby Lee Gatewood's Tavern, and Blue Chicago.

Also think Buddy Guy’s Legends. Buddy Guy, now age 84, is among Chicago’s blues greats. Born in Louisiana in 1936 as George Guy, the legendary guitarist is world-famous for his lightning electric riffs, accompanied by his deeply felt vocals. In the 1990s, Guy’s popularity soared again after an already distinguished four-decade career, and he continued touring and performing live until the coronavirus pandemic hit in early 2020. His hits include “Stone Crazy,” “Damn Right I’ve Got the Blues,” and “Leave My Girl Alone.” When barely into his teens, Guy made his own guitar and learned to play by listening to the radio, copying previous legends such as John Lee Hooker. After performing in New Orleans clubs, he relocated to Chicago in his early 20s and was discovered by yet another legend, Muddy Waters. Guy continued learning from the best, as he worked alongside performers like Little Walter, Howlin’ Wolf, and Koko Taylor. He is the recipient of multiple Grammy awards, including a 2015 Grammy for Lifetime Achievement. Rolling Stone magazine caught up with Guy in June 2020, when he noted that he was then in the longest hiatus of his career due to the nationwide shutdowns of performing arts venues. Guy’s club also suffered damage amid rising protests against police brutality. But the bluesman remained upbeat, saying that the outpouring of people into the streets demanding justice might be just what the country needs to finally set things right. Czech composer Antonín Dvořák is among the world’s great masters of 19th century symphonic form. His Ninth Symphony has achieved lasting popularity among the professional musicians who appreciate its technical achievements, as well as among generations of listeners who love it for its captivating melodies, grandeur of expression, and echoes of American—notably African-American—folk music themes. Dvořák’s Symphony No. 9 in E minor, Op. 95, is specifically entitled “From the New World.” Here’s what you need to know about the composer, his Ninth Symphony, and its connection to African-American spirituals: Dvořák’s Immigration to New YorkDvořák arrived in the United States in September 1892, wife and children accompanying him. He was taking up a position as music director of the National Conservatory of Music of America, hired away from Prague by wealthy patron of the arts Jeannette Thurber. The salary was 25 times what Dvořák earned back home, and even came with a perk: he would have summers off. The composer remained in New York until April 1895, working on composing music that incorporated American themes. He finished an “American” string quartet while on summer vacation in the Czech-American town of Spillville in Iowa. Dvořák also conducted a special “Bohemian Day” at the Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. And he composed the New World Symphony. The “New World” SymphonyHe completed the score for the “New World” Symphony in May 1893. One of the reasons Dvořák may have felt a strong connection with African-American folk music was his own Czech cultural nationalism. The Bohemian lands of what would become the Czech Republic were then part of the Austro-Hungarian empire. A Czech nationalist revival gathered force throughout the 19th century, promoting Czech as an alternative to the German language, and elevating Czech folklore themes in literature, art, and music. Dvořák was among the leading exemplars of this Czech national pride. The New York Philharmonic debuted the Ninth Symphony at Carnegie Hall on December 16, 1893. The now-storied venue had only been open for 18 months. Dvořák himself, who had previously conducted at Carnegie Hall on four occasions during his sojourn in the United States, was present in the audience, with the Philharmonic under the leadership of Anton Seidl. The Influence of Harry Thacker BurleighThe National Conservatory, in a rare decision for its time, opened its doors to talented music students regardless of ethnic background or family connections. This included many Black students. Several of the professional connections Dvořák made during his tenure brought African-American music to his attention. One such connection was Harry Thacker Burleigh, the son of an Erie, Pennsylvania, domestic worker. Although Burleigh’s mother had a classical education and knew Greek and French, no other employment was available to her. Always musical, the young Burleigh took a number of clerical jobs, including that of librarian for the National Conservatory’s orchestra while he was studying there on scholarship. Conductors typically work closely with an orchestra’s librarian. This was certainly true of Burleigh and Dvořák. Operetta composer Victor Herbert later noted that Burleigh provided Dvořák with a number of themes used in the Ninth Symphony. This contemporaneous evidence is particularly notable in light of the fact that, even today, some sources discount the influence of African-American musicians on the symphony. Burleigh often sang the spirituals he had learned from his blind grandfather—an enslaved man who later purchased his freedom—for the Czech composer. He, in turn, was a defining influence on Burleigh’s later career as a singer, teacher, and composer. The Influence of Will Marion CookWill Marion Cook, a young violinist and Dvořák’s student at the conservatory, also deepened the great composer’s knowledge of the rich heritage of what were then called “Negro spirituals.” Cook, born in Washington, DC to a middle-class family, would go on to become a noted conductor, composer of Broadway musicals, and teacher of a young Duke Ellington. The Library of Congress lists Cook among the greatest African-American musical talents before the Jazz Age. Cook himself first encountered African-American folk songs when he, at age 12, was sent to visit his grandfather in Tennessee. Dvořák himself later wrote, using the language of the day, that any truly American music would need to draw its main inspiration from “Negro melodies or Indian chants.” He went on to say that “the most potent as well as most beautiful among them” were the “plantation melodies and slave songs,” with their “unusual and subtle harmonies.” Harry Burleigh recalled Dvořák once remarking that the spiritual “Go Down, Moses” was equal in greatness to any of the works of Beethoven. The New World Symphony uses numerous elements that distinguish the spirituals anchored in the lives of enslaved Americans: pentatonic scales, syncopation, and flattened sevenths. While musicologists still debate whether or not Dvořák literally transported traditional spirituals into the work note-for-note, there is no doubt that it was heavily influenced by them, as the composer himself attested. “Goin’ Home” Music scholar Joseph Horowitz told NPR in 2019 that the African-American influences on classical music—on Dvořák in particular—are part of “buried history.” The Czech composer, said Horowitz, became “consumed” by a desire to show America a truer musical portrait of itself by highlighting this contribution to a renewed and more authentically American style. In the first movement of the New World Symphony, the second theme echoes the melody of the spiritual “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.” In the lyrical Largo second movement, Dvořák developed what is now called the “Goin’ Home” theme, played by English horn. Beloved by generations of Americans, this theme is Dvořák’s creation, although it certainly references traditional African-American melodies and harmonies he had picked up. The theme only acquired words in 1922. William Arms Fisher, one of Dvořák’s white students, wrote the lyrics. They referenced the beauty and power of traditional spirituals. African-American churches, along with many others, have adopted the melody into numerous hymnbooks. Notable Performances of “Goin’ Home”“Goin’ Home” was played in tribute by an African-American US Navy accordionist, Graham W. Jackson, in Warm Springs, Georgia, after President Franklin Roosevelt died there. In 1949, Black pianist Art Tatum composed the “Largo” swing, referencing Dvořák’s tune, and in 1958, Paul Robeson famously performed “Goin’ Home” at Carnegie Hall.

The haunting, transformative power of this piece of music has moved people all over the world. In one recent notable performance, the Silk Road Ensemble recorded it under the direction of Yo-Yo Ma. The performance featured a Chinese sheng and an American banjo, with a singer performing in both Mandarin and English. In 1904, Dvořák died in Prague at age 63. One of his obituaries noted the sorrow of so many music lovers, saying specifically that “Afro-American musicians alone could flood his grave with tears.” Music and literature have met and mingled countless times, as composers have taken inspiration from poems, plays, novels, and stories to create listening experiences that bring out new dimensions of original literary works. Many of these musical pieces have become classics in their own right, part of the lasting cultural heritage of humanity. One of the great American poets, Langston Hughes (1901 or 1902 - 1967), is today remembered as a writer who gave voice to the hopes, dreams, and common experiences of African Americans. A leading figure of the Harlem Renaissance in New York, Hughes wrote in numerous genres, but is best-remembered today for his lyrical poems that contain a sense of both the joy of living and the painful path of history within their sinuous lines. Hughes drew enormous inspiration from music to feed his creative process throughout his life. Composer Margaret Bonds and Langston Hughes developed an enduring personal friendship that began a decade after she discovered his poems as a teenage music student at Northwestern University in 1929. Their Friendship Began with His Poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” Margaret Bonds | Image courtesy Wikipedia Margaret Bonds | Image courtesy Wikipedia Born in Joplin, Missouri, Hughes wrote “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” shortly after his high school graduation. The Crisis, the official magazine of the NAACP, published the poem in 1921. Hughes went on to study at Columbia University, becoming immersed in New York’s vibrant cultural scene, which he soon helped shape. “I have known rivers,” the poem opens. Its lines wind down through history, as Hughes’ voices speaks on behalf of the millions of voiceless Black and Brown men and women over centuries who lived, loved, dreamed, and died beside the world’s great rivers, from the Nile, the Euphrates, and the Congo, to the Mississippi. Margaret Bonds (1913 - 1972) was an accomplished musician and composer who had begun composing at age 13. According to Bonds, Northwestern University was a “terribly prejudiced place.” She had made enormous sacrifices to be able to study at a well-known school, and she won prizes in piano and composition during her time there. Yet, due to the practice of segregation, she was not even allowed to use the Northwestern swimming pool. Restaurants in the area refused to serve her. Then one day, going through books at her neighborhood public library outside Chicago, Bonds began reading “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” from Hughes’ first poetry collection, The Weary Blues. Reading it gave her a sense of security, a belief that she, as a young, African American woman, had a rightful place in the world. “I know that poem helped save me,” she said. After They Met, They Began a Long and Fruitful Collaboration Bonds’ discovery of “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” was the touchstone that led her and Hughes to a decades-long artistic collaboration. She finally met him after she finished her university education, at the home of a mutual friend. They became inseparable, “like brother and sister,” Bonds later said, getting to know each other’s families and becoming comfortable in one another’s homes. Bonds even often sent Hughes melodies she had composed, asking him to write lyrics for them. By the mid-1930s, she had set numerous Hughes compositions to music, including “Poème d’Automne,” “Winter Moon,” and “Joy.” Bonds’ interpretation of Hughes’ “Love’s Runnin’ Riot” went on to be performed and recorded by Duke Ellington. In 1940, Hughes and Bonds worked on the revue Tropics After Dark, collaborating with Arna Bontemps, another writer who played a key role in the Harlem Renaissance. Bonds set “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” to music in 1941. Bonds’ music unwinds Hughes’ words at a stately and sonorous pace as it sets to music the historical events in which Black people moved through the world through deliberate or forced migrations. “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” remains perhaps Bonds’ most often-performed art piece, and she always remembered it as among her favorites. Their Collaboration Culminated with the Now-Famous Three Dream PortraitsThe 1959 Three Dream Portraits is a song cycle of three Hughes poems set to music by Bonds. “Minstrel Man,” once notably recorded as a poem read by legendary African American bass-baritone Paul Robeson, is a soliloquy juxtaposing the speaker’s outward mask of frivolity with his inner pain. The irony lies in the fact that this pain went largely unnoticed by the white audiences that typically attended minstrel shows.

“Dream Variation,” the center movement, speaks of “a place in the sun.” It is filled with harmonies gathered from world cultures beyond American borders, and has a joyous sense of movement through dance. The concluding movement, “I, Too,” uses Hughes’ poignant yet ringing words, “I, too, sing America.” Even as the speaker, the “darker brother,” is banished and forced to eat in the kitchen, he feels that when others “see how beautiful I am,” they will invite him to the table, ashamed that they ever excluded him. Critics note that Bonds’ music becomes more self-assured with each of the three movements. It reaches a crescendo of confidence toward the end of “I, Too” that winds down into wistful uncertainty by its concluding notes. This artistic choice by Bonds in the late 1950s mirrored the world around her. The Civil Rights struggle was beginning to gain momentum, with enormous struggle and loss ahead. When Bonds wrote her music for Hughes’ words, the outcome of this struggle was still unknown. Three Dream Portraits remains a deeply meaningful work more than half a century later. Medgar Evers, born in 1925 in the city of Decatur, was a soldier who fought in the invasion of Normandy in World War II before becoming Mississippi’s first field secretary for the NAACP. He was in charge of leading voter-registration drives and directing targeted economic boycotts across the state. In addition, his job involved looking into hate crimes committed against African-American citizens. He launched an extensive investigation into the murder of Emmett Till, the 14-year-old lynched in 1955. As a result, Evers was used to receiving death threats. On one occasion, someone tried to run him over. Another time, someone threw a firebomb at his house, where he lived with his wife Myrlie and their young children. Evers was assassinated in Jackson, Mississippi, on June 12, 1963, by white supremacist Byron de la Beckwith. He was not yet 38 years old. On June 19, 1963, a week after Evers’ murder, President John F. Kennedy sent to Congress the proposed legislation that would become the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, signed into law by his successor, President Lyndon B. Johnson. President Barack Obama officially declared the home of Medgar Evers home a historic landmark in 2017. There have also been a number of songs composed about him. Here are three of the most well-known: “The Ballad of Medgar Evers”The Freedom Singers were one of several noted choral groups active in the days of the Civil Rights movement. The Freedom Singers’ rendition of “The Ballad of Medgar Evers,” also known as “They Laid Medgar Evers in His Grave,” is one of a number of songs memorializing the slain civil rights leader. It was written by Reverend Matthew A. Jones, Sr., a SNCC field organizer who modeled its cadences on the folk song “The Ballad of Jesse James,” making it ideal for choral interpretation. Notably, the lyrics of “The Ballad of Medgar Evers” name his murderer, white supremacist Byron de la Beckwith. Beckwith was not convicted of the slaying until 1994. However, the song lyrics provide contemporaneous evidence that he had immediately been identified as the killer by the community. Strong forensic evidence pointed to Beckwith, who had left his rifle behind at the scene of the crime. Still, the all-white juries in two 1964 trials failed to reach a unanimous verdict. Myrlie Evers never stopped fighting for justice for her husband’s memory. In 1994, Beckwith was finally convicted. He would die in prison in 2001 at age 80. “Too Many Martyrs”As a young man, now-legendary folk singer-songwriter Phil Ochs composed another “Ballad of Medgar Evers” at about the same time as the song written by Jones. The piece by Ochs has a faster tempo, but it also relies on traditional folk ballad rhythms and storytelling style. It begins with the image of “a boy of 14 years” who “got a taste of Southern law.” This is a reference to the murder of Emmett Till. After learning of the Evers assassination, Josh Dunson, a writer for the folk music publication Broadside, was quoted as saying “We’ve already got too many martyrs.” The refrain of the Ochs piece references the many “martyrs” who lost their lives to hate-fueled violence. Ochs later called the song “Too Many Martyrs.” Whatever its title, the song’s relentless pace and highly detailed imagery—describing Evers’ assassination as he stood in his own driveway—continue to elicit a visceral impact on listeners today. Evers got out of his car late on the night of June 12, 1963, after arriving home from a meeting. His assassin used a rifle to fire at him from the cover of a nearby honeysuckle bush, shooting him in the back. Evers died about an hour later. “Only a Pawn in Their Game" Bob Dylan was another folk and protest singer deeply moved by Evers’ murder. Dylan wrote his own tribute to Evers, “Only a Pawn in Their Game." He performed it at the March on Washington on August 28, 1963. Dylan’s song asserted that the murderer was “not to blame,” due to his being “a pawn in their game.” Instead, he depicted Beckwith as just another part of a wider system set in place by others and beyond his control.

Dylan also mentions the many law enforcement officers, white preachers of segregation, Ku Klux Klansmen, and even the governor of the state as other “pawns” in this game. In fact, Mississippi’s former Governor Ross Barnett shook hands with Beckwith in the middle of Myrlie Evers’ testimony at one of the killer’s 1964 trials. Barnett also visited Beckwith in prison. The song’s larger point is that it is not only individuals who need to change, but also a system of entrenched racism. This message continues to be meaningful. However, in 2020, Dylan's lyrics sound hollow and tone deaf to many listeners, particularly because he is white. The song depicts adult human beings as mere chess pieces, rather than as men filled with hatred so strong that it would cause them to support, and sometimes to commit, acts of violence against innocent people. We may not often think of the great composers and musicians of the past as heroes in the sense of being physically brave, or courageous in the sense of putting everything on the line for ideals they believed in. However, behind the great music we know, there are also personal stories of heroism, dedication to causes beyond the self, and steadfast love and kindness that deserve our attention and respect, particularly in today’s chaotic and divisive world. Here are only a few of these heroes from our musical past. Clara Schumann (1819 - 1896)Clara Schumann’s husband, German Romantic composer Robert Schumann, is far more widely known. He created magnificent, intricately virtuosic symphonies and a rich collection of songs and piano pieces, many of them written expressly for her. However, Clara was a highly gifted musician and composer in her own right, and we can attribute her historical neglect to long-standing sexism. In her youth, she was renowned all over Europe as a child prodigy of the piano. Felix Mendelssohn conducted the premiere of her piano concerto, with teenage Clara at the keyboard. She would go on to compose solo pieces and chamber music, and to teach at Leipzig Conservatory. Remarkably, she did all this while caring for her increasingly ill and troubled husband and their many children. The Schumanns had a Romeo-and-Juliet love story. Robert proposed to Clara when she was 18, but her abusive and tyrannical father, Friedrich Wieck, forbade the match. Robert trailed her across Europe as she performed, hoping for a few chance hours together. Friedrich controlled every aspect of his daughter’s life, so she took matters into her own hands and sued him in court. Before the court rejected his claims, her father attempted to gain control of all her concert earnings. He confiscated her piano, stole her letters, and wrote scurrilous slanders against Schumann. Robert and Clara emerged the winners in court and married in 1840. In 1849, Europe was in tumult as revolutions swept the continent, eventually touching the young Schumann family in Dresden. Clara was seven months pregnant, and outside their home peaceful protestors were being gunned down in the streets. Walking through the town the morning after a tense clash, she saw the corpses of those killed and noted the troops knocking on every door to whisk away every able-bodied man to the fighting. Robert Schumann had already shown signs of his severe and life-long mental illness. Clara, desperate to protect him, told the militias he was away from home. To ensure his safety, she devised a plan to spirit him out of Dresden. She left three of her young children at home with a caregiver, to avoid suspicions of the whole family fleeing. Then, she got Robert, their seven-year-old daughter, and herself to the closest train station, talking her way through tense encounters at guarded checkpoints. With Robert and young Marie safely eight hours away, concealed with friends in a small village, Clara returned to Dresden—hiding to avoid detection by patrols of men wielding farm scythes as weapons—and rescued her remaining children from danger. Maurice Ravel (1875 - 1937)French composer Maurice Ravel is likely best known for the orchestral piece Boléro. The composition is used so often in films and television that its rich, stirring music has almost become a cliché. Ravel’s technical mastery, finely tuned sense of melody, and fluidly expressive style are also evident in Pavane for a Dead Princess, his opera The Child and the Enchantments, and the ballet Daphnis and Chloe. Ravel was not a very political man; his personality has been described as intellectual and a little aloof. But in 1914 at age 39, he tried to enlist in the French air force, hoping to serve his country after Austria-Hungary’s declaration of war. Ravel had kept himself anchored to his music for most of his life, separated from the troubles of the rest of the world, but now he felt he needed to become a man of action. Initially, he was rebuffed when the air force thought him too old and unfit. Ravel was a short, slight man who weighed just 91 pounds. However, he was enraged by the deaths of his friends in uniform and wouldn’t take no for an answer. He drove army gasoline trucks near Verdun, where 40,000 men every month were being slaughtered. Hemmed in by enemy fire, he once had to hide in the forest for 10 days. Discharged after contracting dysentery, he was sent home. Critics then and now have often pointed to the violent, clashing rhythms of La Valse (“The Waltz”) as his musical declaration of war against the Viennese enemy. He also composed the piano suite Le Tombeau de Couperin and dedicated each movement to a friend who had died in combat. Benny Goodman (1909 - 1986)Beloved as “the King of Swing,” Benny Goodman was one of the greatest jazz clarinetists and bandleaders the world has ever known. His all-consuming devotion to perfecting his art led to a historic 1938 Carnegie Hall concert in which, for the first time ever, a concert hall audience was treated to a full program of swing music.

This New York-born son of Jewish immigrants from Tsarist Russia started out with a classical training, then quickly became absorbed into the Dixieland and jazz music scenes. He accompanied Billie Holiday in what are now considered landmark performances. Goodman put together his own band in 1934 and went on to create—in solo performances and as a bandleader—what would become some of the 20th century’s most memorable live performance hits and recordings: “Stompin’ at the Savoy,” “Moonglow,” “Let’s Dance,” and scores of others. That 1938 Carnegie Hall concert was historic for another reason, too: Goodman insisted on performing with his racially integrated band. This arrangement was almost beyond the ability of anyone at that time to comprehend. Most performance spaces were strictly segregated. Throughout his career, Goodman worked with integrated ensembles. In the early 1930s, he had at first hesitated to bring Black performers into his band, but his merciless search for the best sound and his commitment to acknowledging common bonds of humanity won the day. One of the first events in American public life to break the color barrier, that initial Carnegie Hall concert featured half a dozen Black musicians, including Lester Young on sax, Lionel Hampton on the vibraphone, and Count Basie and Teddy Wilson on piano. Hampton later recalled that Goodman’s decision to work alongside Black musicians came not from a desire for fame or money, but from the bandleader’s heart. He recalled Goodman saying that the “white keys and the black keys” just needed to be allowed to harmonize. Musicians around the world have paid tribute to civil rights leader and human rights hero Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The tributes began immediately after his death by an assassin’s bullet on April 4, 1968, in Memphis, Tennessee, and have continued over the decades since then. Here are a few of the songs honoring Dr. King that have conveyed grief, remembrance, inspiration, and hope to millions of Americans, as well as to people around the world struggling to assert their rights amid bigotry and violence. 1. “Abraham, Martin and John”“Abraham, Martin and John,” with words and music by rock musician Dick Holler, was written as a tribute to Dr. King and to presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy, who was assassinated just shortly after King was gunned down. It was a tumultuous time, and communities nationwide—the black community in particular—were torn apart by anger and grief. Holler’s spare, repetitive chords, and gentle, evocative, and simple words—as originally recorded by singer Dion DiMucci—seemed just right for the moment. The song references, in turn, President Abraham Lincoln, President John F. Kennedy, King, and Robert Kennedy, each of whom “freed a lot of people” but died violent, untimely deaths amid cataclysmic events that would change the course of history. The song’s four verses are identical except for the name of each man. Each one asks the listener if anyone has seen “my old friend Abraham,” “my old friend John,” and so on. The concluding words paint a picture of the four men walking side by side over a hill together. The words and sentiments may be considered old-fashioned—even simplistic—to some listeners today. But for many who were alive at the time and looked up to King and the Kennedy brothers as the best of America, they can still summon tears and—often—a smile of wistfulness for the bright future that these men stood for that remains only partially realized. 2. “Happy Birthday”“Happy Birthday” by Stevie Wonder is a song written for a didactic purpose, but one whose lyrics and music still bring joy to audiences who may not even be aware of their original meaning. Wonder, the blind superstar singer-songwriter whose poetic lyrics and musically complex and ingenious melodies embody the joys and struggles of the 1960s and ‘70s, has always been an activist. So, he wrote “Happy Birthday” in 1981 as part of a campaign to get King’s birthday declared an official national holiday. At the time, there was vigorous opposition from conservative politicians and interest groups to a federal holiday honoring King. Wonder’s up-tempo beat and lyrics celebrate King and ask how anyone could oppose the national recognition of “a man who died for good.” Wonder’s lively refrain of “Happy Birthday to ya!” is still very danceable and much deserving of celebration. In 1982, Wonder joined King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, in delivering a petition with 6 million signatures on it in support of the holiday directly to the Speaker of the United States House of Representatives. The following year, President Ronald Reagan signed into law a bill declaring Martin Luther King, Jr. Day a federal holiday to be observed every third Monday in January, beginning in 1986. 3. “Pride (In the Name of Love)”“Pride (In the Name of Love)” by the Irish rock group U2 was released in 1984 as the lead single on the album “Unforgettable Fire.” The band’s lead singer, Bono, initially put together a set of lyrics intended to condemn the militaristic focus of the United States under President Ronald Reagan’s administration. But after a 1983 visit to an exhibit honoring King’s legacy at Chicago’s Peace Museum, Bono began crafting the song to highlight King’s achievements, as well as those of other martyrs to the cause of peace throughout history. The finished lyrics echo King’s own phrases, such as “Free at last,” and “One man come in the name of love.” The phrase “pride” in the title is used in two ways in the lyrics. One kind of “pride” that Bono refers to is the pride of aggression and violence. The second is the kind of pride moral heroes like King embodied, pride in being on the side of justice and freedom for all people. 4. “The King”Pioneering New York hip hop composer and performer Grandmaster Flash, with his group the Furious Five, produced another moving tribute to King, with a song simply titled “The King,” which was featured on the 1988 album On the Strength. The song’s beats and rhythms alone serve as an example of Grandmaster Flash’s classic and fresh musicianship, even as its lyrics provide a lasting artistic memorial to King, a man who “brought hope to the hopeless.” “His name is Martin Luther King,” and he dedicated his life to “making freedom ring,” the rap song proclaims. It relates how King, who was fearless in his convictions, was vilified and persecuted as a black man taking constructive action for freedom for all blacks, and it laments the fact that too many turned away from King’s message of peace and hope, during his lifetime and after. 5. “A Dream”“A Dream,” which is rapper Common’s 2006 tribute to King, samples the words of the hero’s most famous speech. The music video for the song incorporates historical footage of King delivering the speech at the March on Washington in 1963.

Common weaves King’s original words and story (“I have a dream”) into his own perspective (“I got a dream”) as a 21st century black man “born on the blacklist” to struggle against enduring racism, but working to find the hope that still endures through the inspiration he draws from King’s words. Common’s performance, featuring fellow American rapper will.i.am, elaborates on King’s words “one day” throughout its lyrics, and adds, of dreams, “I still have one.” Many young people—and even many adults—are not aware that many of the world’s foremost musicians and performing artists have lived with one or more disabilities. Here are six of some of the best-known singers, songwriters, and performers of the 20th and early 21st centuries who can serve as vivid role models of creativity and perseverance for musicians of all types of ability: 1. Django Reinhardt Django Reinhardt (1910 - 1953) was a Roma musician born in an itinerant camp near Paris. As a young man, he became skilled on banjo, violin, and guitar, but at age 18 received severe burns from a caravan fire. The accident left him with one leg paralyzed and with a badly damaged hand. He relearned how to play guitar with his hand injuries. He also relearned how to walk using a cane. At only 24 years old, he joined with violinist Stéphane Grappelli to co-lead the Quintette du Hot Club de France, and later toured with Duke Ellington. A master of improvisation, Reinhardt is beloved today by scholars and music-lovers for the exceptional originality of his compositions. He is honored as one of the most richly creative spirits in the history of jazz. 2. Hank Williams Hank Williams (1923 - 1953) was one of the world’s major country music stars, known for his talents as a singer, a guitarist, and a songwriter. Williams gave intense, lyrical performances of songs like “Your Cheatin’ Heart,” “Howlin’ at the Moon,” “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” and “Lost Highway.” After he joined Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry he catapulted to international fame. His songs remain iconic and deeply moving expressions of the best of American popular music. Williams was born with spina bifida oculta, a malformation of the spinal column that typically goes unnoticed, but that in his case resulted in lifelong chronic pain. Williams was a driven composer and performer who threw himself completely into his music. His use of drugs and alcohol intensified after a failed surgery to repair his spinal defect, and he died of a heart attack at age 29. In 2010, Williams received a posthumous Pulitzer Prize citation for the extraordinary technical and emotional quality of his compositions, and for his role in transforming American country music on the world stage. 3. Rosemary Clooney Rosemary Clooney (1928 - 2002) may be more famous today as the aunt of movie superstar and humanitarian George Clooney. But in the mid-20th century, the Irish-American jazz and pop singer was among the world’s best-known female vocalists, and was widely beloved by fans the world over. She had an extraordinarily rich vocal quality and an unbeatable sense of timing and phrasing. Her 1951 recording of “Come On-a My House” topped the charts in its day, and remains popular. After the assassination of her friend Robert F. Kennedy, a shock that was exacerbated by drug addiction, Clooney was hospitalized for several years. She relied on her music to help pull herself through. She battled bipolar disorder for decades, writing courageously about her experiences with the condition in her 1977 autobiography, This for Remembrance. The year that she died, she received a Grammy Award for lifetime achievement. 4. Itzhak Perlman Itzhak Perlman (born 1945) is an Israeli-born virtuoso of the violin. His range of interpretation and mastery of the technicalities of musicianship have caused numerous critics to rank him among the greatest musicians in history. Perlman contracted polio as a 4-year-old, and as a result he uses crutches to help him walk. As a teen, he made his debut at Carnegie Hall in New York. In the decades since, Perlman has played and conducted with major orchestras around the world. He has recorded an extensive catalog of classical, jazz, traditional Jewish, and theatrical music, including the solo violin portions of John Williams’ score for the film Schindler’s List. He has earned 15 Grammy Awards to date. Perlman, a vocal advocate for music education and for people with disabilities, also received a Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2015. 5. Diane SchuurDiane Schuur (born 1953) has been blind from birth due to a condition called retinopathy of prematurity. She is also one of the leading jazz vocalists in the world today as well as an accomplished pianist. Schuur, who began performing for family and friends while still a preschooler, went on to a genre-bending recording and performing career, earning two Grammy Awards to date. Heavily influenced by jazz legends like Dinah Washington, Sarah Vaughan, and the blind pianist George Shearing, Schuur rose to fame in the mid-1970s. Her smooth, effervescent interpretations of classic and contemporary songs made her a hit with the public, with musicians like Stan Getz and Stevie Wonder championing her talent. In 2020, Schuur released a new album, Running on Faith. It includes interpretations of her favorite standards, including a thrilling rendition of Washington’s signature song, “This Bitter Earth.” In 2000, Schuur was honored with a Helen Keller Achievement Award from the American Foundation for the Blind. 6. Stevie Wonder Stevie Wonder (born 1950) needs no introduction, even to music fans born long after the peak of his fame. Born Steveland Morris, the now world-famous singer received too much oxygen in an incubator as a newborn, which resulted in permanent blindness. As a young boy growing up in inner-city Detroit, Wonder idolized musicians like Ray Charles—who was also blind—and learned to play multiple instruments.

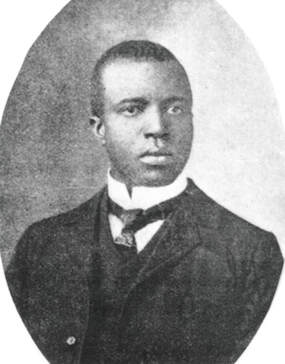

When he was only 11, Wonder was discovered by singer Ronnie White of The Miracles, a popular Motown singing group. At 12, he cut his first album for Motown Records, beginning a varied career of brilliant performance and composition that endures into the present. Wonder’s work ranges from lighthearted love ballads like “My Cherie Amour” to powerful, driving, musically intricate pieces like “Superstition,” to songs that capture the chaos, deprivation, passion, and hope of the social changes of the 1960s and early ‘70s. Albums like Songs in the Key of Life (1976) have achieved milestone status among music critics, and Wonder has earned a total of 25 Grammys to date. Despite centuries of injustice and limited opportunities, African-Americans have made countless contributions to science, medicine, public service, and the arts, among many other areas. American music, for example, would be far less rich, innovative, and memorable without the creative work of black composers. Scott Joplin, Duke Ellington, and Florence Price were gifted musicians. Additionally, their lives exemplify the obstacles 20th-century people of color had to overcome regardless of profession. Here’s what you need to know about their lives and work: Scott Joplin Image courtesy Wikipedia Image courtesy Wikipedia Around the turn of the 20th century, Scott Joplin’s innovations in syncopated ragtime music made him one of the most acclaimed and influential American pianists and composers. His “Maple Leaf Rag” and “The Entertainer” are now staples of the popular repertoire. Later audiences rediscovered this “King of Ragtime” through the use of his music in movies such as The Sting. The 1973 production won multiple Oscars, including one for Marvin Hamlisch’s adaptation and orchestration of Joplin’s music into its score. Joplin was born into a family of musicians in about 1867, probably in northeast Texas. He grew up in Texarkana and studied piano in his early teens. He performed in Chicago at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, and two years later studied music at a segregated school in Missouri. After his early work made him famous, Joplin moved to St. Louis. Hoping to reduce the prejudice shown by some critics to ragtime because of its African-American origins, Joplin published an instructional series called The School of Ragtime: Six Exercises for Piano. His ambitions as a composer of more traditional music led him to compose the opera A Guest of Honor and the ballet Rag Time Dance. Before his death in 1917, Joplin’s multi-genre operatic theater piece Treemonisha, whose African-American themes prefigured George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, was presented in a small-scale version. Critics have noted Treemonisha’s vivid blending of influences from Richard Wagner to Giuseppe Verdi to Tin Pan Alley. Notable recent stagings include a 2019 production at East London’s Grimeborn music festival. Duke Ellington Image courtesy Wikipedia Image courtesy Wikipedia Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington composed the score for Symphony in Black: A Rhapsody of Negro Life, which was also the film debut of then 19-year-old singer Billie Holiday. Revered as the most talented American jazz composer and conductor of his day, Duke Ellington wrote thousands of scores and is largely responsible for the distinctive sound of the Big Band era. Born in Washington, DC, in 1899 to a middle-class family that encouraged his artistic ambitions, Ellington studied piano at age 7 and began performing in ragtime bands in his teens. Working in New York City from 1923, he eventually assembled a 14-piece orchestra. Ellington’s band became a fixture at Harlem’s Cotton Club in the 1920s and ‘30s, and he hired musicians who were themselves major figures in the development of jazz. This group of musicians became a wildly popular touring ensemble, appeared in multiple films, and went on the road in Europe from 1933 to 1939. Ellington’s music, and swing and jazz in general, were popular among anti-Nazi German youth. As a result, he was among the many black performers banned from working in Germany after the mid-1930s. However, at that time, the Cotton Club was an all-white establishment as far as patrons were concerned, and black musicians had to enter by the back door. While on tour in the United Kingdom in 1933, Ellington’s troupe was turned away from several hotels, and he suffered many other such slights on tour in the United States. This inspired him to begin working on behalf of the NAACP’s fight for racial justice. His extraordinary talent and personality forced white critics and audiences to take African-American music and performers seriously. By the late 1930s, Ellington had begun composing long-form pieces, and the 1940s saw him compose a string of fast-tempo hits and pieces rich in tonal color. Ellington also expanded his talents into theater scores, including the 1964 production My People, a tribute to the Civil Rights movement. Ellington’s band continued touring the world with him for many years. Many of the same performers remained with him for four decades or more. His regal demeanor and charm continued to draw audiences until shortly before his death in 1974. Florence Price Image courtesy Wikipedia Image courtesy Wikipedia Florence Price is one of the few African-American female composers of symphonic music whose work achieved significant recognition from white audiences during her lifetime. She was the first black woman to have her work performed by a well-known orchestra. In 1933, the Chicago Symphony performed her Symphony in E minor. One critic wrote that the piece was “faultless” in its passion and restraint. Many of Price’s hundreds of classical compositions were anchored in the tunes and rhythms of classic African-American spirituals. They were performed throughout the United States and Europe. Marian Anderson, one of the world’s great contraltos and herself a breaker of color barriers in a segregated society, included Price’s song “My Soul’s Been Anchored in de Lord” among the pieces she sang at her famous 1939 concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Born in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1887, Price studied music as a child under the guidance of her mother, a schoolteacher and pianist. She went on to study at Boston’s New England Conservatory of Music, a rare opportunity for a black woman in those days. Before returning to Arkansas to marry, she spent two years teaching music at Clark University in Atlanta. Back in Arkansas, she continued to teach and compose. However, because she was African-American, she was refused admission into the Arkansas State Music Teachers Association. Despite the international reputation she earned, her work was knocked well-known in the decades after her death in 1953. In 2009, the new owners of Price’s summer home in Illinois discovered a long-lost trove of her manuscripts. At that time, musicians began to edit, share, and record them, to the delight of new audiences. The artistry shown in a violin performance is highly individual and subjective. Most musicians can achieve competence in playing the instrument. However, if you have shown the interpretative sensitivity, technical virtuosity, charm of personality, or striking originality of expression that moves them into a class by themselves. Here are short biographies of four outstanding performers whose dedication and talent have moved audiences over the centuries. 1. Niccolò Paganini  Image courtesy Wikipedia Image courtesy Wikipedia Niccolò Paganini (1782 - 1840) is perhaps the first musician who can be considered a virtuoso of the instrument. He remains venerated by violinists and the general public alike. His charisma garnered him a cult-like following during his lifetime. His impact on the entire later history of how the violin is played, and how violinists perform on stage, cannot be overestimated. Born in Genoa, Italy, Paganini debuted as a performer the year he turned 11. As a young man, he toured Lombardy while also getting entangled in a number of romantic escapades. At one point he pawned his violin to settle his gambling debts. Biographers record the story that a French merchant then gave him a Guarneri in recognition of his talents. Paganini was also a gifted composer. His 24 Capricci for Solo Violin remain staples of the classical repertoire. From 1828 onward, he undertook tours of England, Scotland, and the Continent, amassing a personal fortune in the process. It was Paganini who commissioned the great French composer Hector Berlioz to create the symphony Harold in Italy, although the virtuoso considered the work unchallenging and never performed it. Paganini’s technique called on a wide-ranging scheme of harmonics and his talent for playing pizzicati. He made up his own innovative methods for tuning and fingering, and displayed a genius for improvisation. A whole raft of legends grew up around this Romantic-era figure, including one that says he got his extraordinary musicianship thanks to a deal with the devil. 2. Jascha Haifetz Jascha Heifetz (1901 - 1974) started his career as a violinist when he was 5 years old. He was soon playing in Berlin, Prague, and Warsaw and performing complex works that included Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto. At age 16, he enjoyed a spectacular debut at Carnegie Hall. The young refugee from Lithuania gave a performance that one music historian has called “like electricity.” Heifetz showed not only an almost unbelievable level of technical proficiency in his instrument, but an immense warmth of feeling and interpretation to match. Heifetz obtained United States citizenship at age 24 and thereafter toured the world. He commissioned a number of violin concertos and himself became a noted transcriber of great works by Bach and Vivaldi into pieces for the violin. Later in life, he taught at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Heifetz was one of the undisputed 20th-century masters of the violin. PBS showcased his legacy in a special broadcast in its American Masters series that called him “God’s Fiddler.” 3. Itzhak PerlmanItzhak Perlman, born in 1945, often tops critics’ lists of the greatest living classical violinists. He has an instantly recognizable bold and exuberant technique. He has remarked that the best technique doesn’t reside in the ability to elicit notes rapidly from the instrument, but in the capacity to evoke rich and surprising tone and color. A renowned teacher and composer as well as a performer, the Israeli-born Perlman has become a pop culture icon. Between the years 1977 and 1995, he racked up 15 Grammy Awards. He is also the recipient of a U. S. Medal of Freedom, a Kennedy Center Honor, and numerous other accolades. Perlman has also made appearances on the children’s educational television show Sesame Street. In a 1981 segment, he movingly demonstrated the difference between “easy” and “hard,” walking onto the stage using crutches (the result of childhood polio) before taking up his violin to play a lively passage. Perlman’s focus on teaching and philanthropy is exemplified in the Perlman Music Program he and his wife established in the 1990s. The program provides training and support to teen string musicians of exceptional promise. 4. Hilary Hahn Hilary Hahn, born in 1979, is known for her dynamic, sensitive interpretations of works by a varied list of composers from Bach to Stravinsky. She began studying the Suzuki method at age 4, made her orchestral debut at age 11 with the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, performed on her first classical recording at 16, and has gone on to receive numerous international awards, including two Grammys before she turned 30.

In 2015, she received her third Grammy for her album In 27 Pieces: The Hilary Hahn Encores. In hundreds of live solo performances, she has been accompanied by the world’s premier orchestras. Hahn has spent her career making classical music accessible to younger audiences. She has performed for films and with alternative rock groups, and has cut a string of successful classical albums, always with a warm and personal approach. Hahn’s popular social media accounts, a signature component of her educational mission, feature running commentary from the point of view of her violin case as it travels with her around the world. In 2010, American composer Jennifer Higdon received a Pulitzer Prize for the violin concerto she wrote specifically for Hahn. Higdon created a piece combining technical virtuoso flourishes with deep, meditative flow, which she tailored to Hahn’s immense lyrical range and ability to negotiate complex changes in meter. Most experts date the Baroque period in classical music from about 1600 to 1750, putting it between the polyphony of the Renaissance and the era of Classicism (the period after the mid-18th century distinguished by the works of composers such as Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, and Schubert). Compositions from the Baroque period are typically marked by their grandiosity and drama as well as the numerous ways in which composers used the technique of counterpoint to express musical themes and ideas. Developments in the music of this period parallel those in the other arts—for example, massive and ornate buildings such as St. Paul’s Cathedral in London and the Caserta Royal Palace in Rome. Venetian Baroque-era churches, built with two opposing galleries, were ideal for the performances of two ensembles of musicians playing at the same time. A complex formThe concept of two voices or groupings in contrast with one another is a central idea in Baroque composition. Concertos (known in Italian as concerti grossi) featured a solo instrument or voice playing or singing along with a full orchestra. They were a favorite among Baroque composers. Baroque music tends to emphasize a bass line set against a melody. A cello, for example, might deliver the bass, while a vocalist sings a melody. The technique of counterpoint is central to the development and performance of Baroque music. Simply put, counterpoint is the art of combination. A composer working with counterpoint will juxtapose two or more separate melodic lines in a single composition. In counterpoint, individual melodic lines are known as “parts” or “voices.” Each part or voice has a distinct melody. The term “counterpoint” is sometimes incorrectly conflated with polyphony. Polyphony refers to the presence of at least two individual melodic lines in a composition. Although counterpoint evolved out of polyphonic music, counterpoint is a much more complicated technique. True counterpoint involves a complex handling of the several melodic lines of a composition to fashion an acoustically and emotionally meaningful and harmonious whole. The organ and the harpsichord are perhaps the instruments audiences most acquaint with Baroque music. During the Baroque period, these instruments offered two keyboards, allowing the musician to transfer from one to the other to create the rich blending of the contrasting sounds. A centuries-old technique that continuesComposers of the Classical period were usually steeped in the techniques of Baroque composition from their early years. Some, like Mozart and Beethoven, would go on to employ counterpoint extensively in their own later works, written well into the Classical era. Counterpoint continues to find favor today among musicians, composers, and even mathematicians, who have devoted much effort to explaining its symmetry and intricacy in terms of numerical relationships. The supreme artistry of BachNumerous critics and teachers have found the Brandenburg Concertos of Johann Sebastian Bach to represent a pinnacle of the development of the concerto grosso form, and of the Baroque style itself. Bach created these works over the span of the second decade of the 18th century, one of the happiest periods of his life. The six compositions masterfully weave together the component threads played by a smaller orchestra and by several solo groups. Music scholars point out that the scale of the Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 features so many soloists that it is more of a symphony than a concerto, in fact. Bach brought in oboes, horns, a bassoon, and a solo violin. And the third of these concertos features performances from no fewer than three cellos, three violas, and three violins. Unique among these concerti, Brandenburg Concerto No. 6 features not even a single violin; instead, it focuses on lower-voiced string instruments. Three centuries after their composition, the rich-toned, lilting Brandenburg Concertos remain among the most popular and beloved works in the classical repertoire. The art of fugueBach was a master of the fugue, and many musicologists revere his late work The Art of Fugue as one of his most significant creations. A fugue is a piece of music—or a part of a larger composition—that offers finely tuned and mathematically pleasing use of a central theme (the "subject") and numerous restatements and reconfigurations of that theme. In a fugue, the subject is taken up by other parts that are successively woven together. A fugue begins with an exposition, introducing the listener to the central subject. The subject then plays out in different parts, becoming transposed into various keys that serve as “answers” to the essential statement of the subject. A fugue can unfold over as many statements, restatements, and key changes as the composer would like, and can be as short or as long as desired, as well. Baroque composers worth knowingGramophone magazine, one of the world’s premier authorities in classical music criticism, recently put out its 2019 edition of the Top 10 Baroque composers.

Bach heads the list, with the Gramophone team noting that he continues to enjoy a status in music equivalent to that of Shakespeare in literature or da Vinci in the visual arts. The publication particularly recommends Bach’s St. Matthew Passion as a supreme example of his musicianship and of the Baroque style. Next comes Antonio Vivaldi, whose lavish, ornate compositions echo the culture of his native Venice at the time. Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons is perhaps the best known of his works today. This lilting, exuberant hymn to the beauty of earth’s changing seasons is known for its exquisite craftsmanship. George Frideric Handel’s lively, upbeat Baroque compositions are other essentials for anyone becoming familiar with the era. His towering oratorio Messiah remains a not-to-be-missed composition for both music lovers and those devoted to the Christian faith. The experts at Gramophone additionally nominate English composer Henry Purcell, composer of Dido and Aeneas and other operas, to this select group. Claudio Monteverdi, remembered as a bridge between Renaissance polyphony and the early Baroque style, also made the list, as did Domenico Scarlatti, Jean-Philippe Rameau, Georg Philipp Telemann, Arcangelo Corelli, and Heinrich Schutz. |

Photo used under Creative Commons from Marina K Caprara

RSS Feed

RSS Feed