|

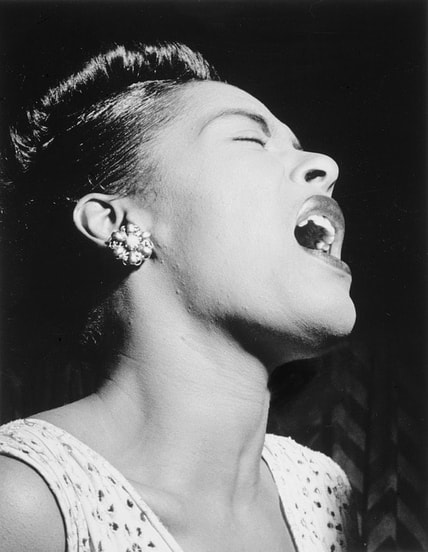

In 1939, Nazi Germany began an international war based on mistaken, hateful, and deadly ideas about a “master race.” That year, the United States also struggled under the strain of its own racism, with the struggle playing out in the world of music through now-iconic performances by Black American singers Billie Holiday and Marian Anderson. Lady Day fights to perform a haunting song Billie Holiday Billie Holiday A legend during her short lifetime, Billie Holiday was one of the most gifted, original singers the world of jazz has ever known. Her 1939 recording of “Strange Fruit” became an indelible part of music history—and the civil rights movement. This tragic, deeply evocative song was written and sung as a deliberate protest against lynching, although it never directly refers to it. But the meaning of “strange fruit” hanging from Southern trees is agonizingly clear, as is the song’s graphic rejection of white supremacy. Abel Meeropol, a poet, songwriter, activist, and teacher at New York’s DeWitt Clinton High School, was unable to put a photograph of a lynching he’d seen out of his mind. He wrote an impassioned poem, later published in a teacher’s union magazine. He set the words to music, and one evening at the Greenwich Village club Café Society, he offered the song to Billie Holiday. It took great courage for Meeropol, a white Jewish man and the son of immigrants, to write the song, and for Holiday, a well-known performer but still a Black woman in a time of often-vicious racism, to perform it. Holiday’s goddaughter later told an interviewer that when her godmother performed the song in front of white audiences, the effect was “viscerally shocking.” Radio stations were afraid to play “Strange Fruit.” Clubs tried to get Holiday to leave it out of her sets. This was a time when performers and activists were often accused of being Communists, and when people who struggled with addiction, like Holiday, were treated with public scorn or jailed. Government agents threatened Holiday with arrest if she continued to perform “Strange Fruit.” She refused, and it became her signature song. For years, Federal Bureau of Narcotics chief Harry Anslinger harassed and stalked Holiday, trying to arrest her for drug use. She continued to perform “Strange Fruit,” even for white audiences in the Deep South. Anslinger, whom history reveals as a racist with a hatred for people with addictions—in particular Holiday—had her arrested while she was being treated in the hospital for liver disease. Anslinger refused to allow her to continue methadone treatment to wean her from her heroin addiction. Holiday died soon after, in 1959. Biographers have commented that it’s not too much to say that her insistence on performing “Strange Fruit” killed her. In 1999, Holiday’s first studio recording of the song was selected by Time magazine as its choice for the song of the century. Marian Anderson’s quiet dignity breaks musical color barriers Marian Anderson | Image courtesy GPA Photo Archive Marian Anderson | Image courtesy GPA Photo Archive The year 1939 was also a watershed one for Marian Anderson, the world-famous operatic contralto with the kind of voice conductor Arturo Toscanini praised as coming along only “once in a hundred years.” As a Black woman, Anderson had been denied access to perform at Constitution Hall in Washington, DC, a segregated venue owned by the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). So, on April 9, in a concert that stands as a focal point of the civil rights movement, she performed on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial instead. Anderson later remembered her terror before the event. Although she had performed to acclaim across Europe and the United States, this crowd of 75,000 would be the largest she had faced. But she wrote that she “could not run away” from what she knew she needed to do. The evening was chilly, and Anderson, a regal silhouette standing in front of the statue of another monumental figure, hugged her fur coat around her. She took a deep breath and began her performance with the patriotic song “America,” singing, “My country, ‘tis of thee” in a strong, resolute voice, with phrasings filled with power and sweetness. Accompanied by a single pianist, Anderson continued her half-hour concert with “O Mio Fernando,” an aria from Donizetti’s opera La Favorite, followed by Schubert’s arrangement of “Ave Maria,” Henry Burleigh’s arrangement of the traditional spiritual “Gospel Train,” the Edward Boatner spiritual “Trampin’,” and “My Soul’s Been Anchored in the Lord.” Notably, this last piece is a spiritual arranged by Black American composer Florence Price, whose large body of work was only recently rediscovered. The announcer broadcasting the event to an audience of millions stated that Anderson was not able to find an auditorium large enough to fit the many people who wanted to hear her. But that wasn’t it at all. Howard University had invited Anderson to perform in its concert series, but because of her status as an international icon, the school needed an outside venue that could accommodate the anticipated audience. Constitution Hall seemed the ideal choice, but the DAR’s contract specified that the space was only open to white performers. And, ironically, the nation’s capital itself was part of the segregated South. People across the country were outraged. Eleanor Roosevelt resigned her DAR membership, stating that she could not in good conscience remain a member. The DAR refused to back down, even for the First Lady. NAACP executive secretary Walter White had the idea of performing at the Lincoln Memorial. As a national monument, the property was under federal control. So, it was Interior Secretary Harold Ickes who led Anderson to her place on stage. In introducing her, Ickes told the desegregated audience, “Genius draws no color lines.” Marian Anderson would live to be 96 years old, but the Lincoln Memorial concert would always be the defining moment of her career. Anderson was not a vocal civil rights activist, but she believed that if she performed with grace and dignity, that would be enough to help shatter bigoted stereotypes and elevate future prospects for Black Americans. But music historians note that her concert on those steps that spring day in 1939 was the start of a new era for Black musicians and performers. It was also yet another early event that would help ignite the passion of the civil rights movement in the coming decades, and one that remains a source of inspiration and pride. Comments are closed.

|

Photo used under Creative Commons from Marina K Caprara

RSS Feed

RSS Feed