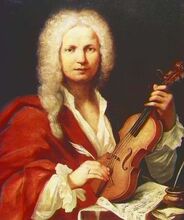

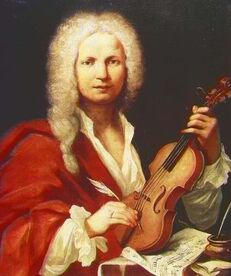

Vivaldi | Image by Wikipedia Vivaldi | Image by Wikipedia Antonio Vivaldi, born in Venice in 1678, achieved fame during his lifetime as one of Europe’s greatest composers. His works have continued in popularity over the centuries—his “Four Seasons” and other richly textured concerti, as well as his operas, are still beloved by listeners all over the world. Vivaldi’s influence on the development of Baroque music, particularly on the emerging form of the concerto, cannot be overstated. Even scholars, however, often overlook how he opened doors for the participation of women in music. Here are a few facts about Vivaldi’s work with an extraordinary group of Venetian female musicians, and how they themselves achieved renown for their gifts in an age when few women and girls had such an opportunity. “The Red Priest” and the orphanageVivaldi worked with the church and orphanage of the Ospedale della Pietà in Venice sporadically from 1703 to 1740. An ordained priest nicknamed “Il Prete Rosso” (“The Red Priest”), most likely due to his vivid red hair, Vivaldi soon ceased to administer the sacraments and concentrated on his work as a composer and teacher. At the Ospedale, he served as a violin master and, later, a concert master. He also composed large numbers of works to be performed by one of the world’s most accomplished—and largely unknown—musical groups: a chorus and orchestra made up entirely of orphaned girls and young women. The long history of the orphanage The Ospedale was a creation of the Middle Ages. Founded by a 14th-century Franciscan priest as a charitable home for orphans, it took in both boys and girls who had lost their families to famine, plague, and other horrors that were common in the Europe of that time. It was attached to the Church of Santa Maria della Pietà, which also served as a public hospital. Throughout the Middle Ages and early modern period, such institutions—a combination hospital, orphanage, and musical conservatory—flourished in Venice. The Pietà was one of four major ospedali that made the city a must-visit musical destination until the fall of the Venetian Republic at the close of the 18th century. Marketing a music schoolThe Ospedale needed a continuous supply of generous patrons in order to feed, house, and clothe the increasing number of children within its walls. Its most creative—and best remembered—marketing effort involved establishing a girls’ choir, composed of its orphaned singers and musicians. The school would test each child at around age 9, to see if she had the needed flair for music. If a girl showed promise, the school made sure that she would have access to the finest musical education possible. (Researchers believe that many of the girls were not, in fact, orphans at all but the illegitimate children of noblemen, thus providing an additional explanation for the lavish expenditure of funds on a fine musical education.) Giving young women performers a voiceBeginning in the 1600s, the Ospedale’s girls’ choir performed in religious pageants to which the population of Venice was invited. By the following century, the fame of this orchestra was such that visitors from all over Europe traveled to Venice to hear, incidentally providing significant new revenue streams for the church and orphanage. Some of the young women performers became legendary, earning nicknames based on their talents. There was “Maria of the Angel’s Voice,” for example, and “Laura of the Violin.” But of the hundreds of girls who lived at the Ospedale, only a few dozen at a time had the talent necessary to become members of the orchestra and chorus. Vivaldi’s compositions for the schoolVivaldi became the most famous of all the renowned instructors of the Ospedale’s girls’ orchestra and chorus. He composed numerous cantatas, concertos, and sacred works specifically for his pupils to perform. One stellar example: He created “Gloria in D Major,” one of the finest compositions in the entire repertoire of sacred music, for the group. The girls sang this piece while situated high up in the top-most galleries of the church, where they would be concealed from the curious stares of tourists and the rough-and-tumble public. The fact that they were afforded an additional layer of protection by a latticed grille only served to enhance the atmosphere of lyrical majesty and mystery of the Gloria in performance. Vivaldi built the Gloria’s dozen small movements into a joyous praise song for God and God’s creation, with the music depicting moods from deep melancholy to bursts of happiness. A deeply moving novelIn 2014 American author Kimberly Cross Teter published a young adult novel, Isabella’s Libretto, a work of historical fiction based on the girls’ orchestra at the Ospedale. Isabella, the novel’s protagonist, is an abandoned infant taken in by the orphanage. She grows to be a gifted young cellist with dreams of one day performing a work that she hoped Vivaldi would create especially for her. But Isabella is also a free spirit and an annoyance to the Ospedale’s head nun, who sets out to tame her by requiring her to give cello lessons to a new pupil whose burned face testifies to her escape from the fire that killed her family. Isabella finds the grace within herself to rise to this challenge, even as the passing years school her in the bittersweet changes that adulthood brings. Her favorite teacher marries and leaves the orphanage, reminding Isabella that any girl who leaves is bound by the Pieta’s rules from ever performing music in public again. And Isabella herself must weigh her love for her art with her growing preoccupation with thoughts of a young man who seems to want to pursue her. Her struggles with her decision about which future she wants for herself make for compelling reading and will draw in empathetic readers. A resplendent picture bookStephen Costanza’s 2012 jewel-toned picture book Vivaldi and the Invisible Orchestra mines the same fascinating ground to tell the story of the Ospedale for younger readers. In this treatment, orphan girl Candida becomes a transcriber of Vivaldi’s emerging works, creating sheet music for the use of the performers in the “Invisible Orchestra”—so called because the female players performed from places of concealment. Candida’s value goes unappreciated, until the day a poem she composed finds its way into the sheet music, and her own creative gifts receive their due. In the author’s imagination, Candida’s sonnets provide Vivaldi with the inspiration he needs to produce his “Four Seasons,” perhaps his most famous and beloved work. The Ospedale todayThe Church of Santa Maria della Pietà still bears a nickname signifying it as “Vivaldi’s Church,” even though construction on its present building on the Riva degli Schiavoni was not finished until decades after his death. Today, the church stands adjacent to the Metropole Hotel, which was built up around a portion of the older Ospedale that had housed the music room.

The present church, constructed in the mid-18th century, recently underwent renovation after having fallen into disuse and disrepair and has reopened for concerts. Today, the church’s social welfare outreach program is still in operation, serving its community with early education programs for young children and parents in crisis. Additionally, a museum exhibiting some of the items associated with the centuries-old Ospedale is situated nearby. Whether tone poems are enjoyed in a concert hall or played in a simplified arrangement in school or at home, they offer young music students a rich variety of musical experiences. A tone poem is a musical composition designed for a full orchestra. It is designed to evoke, through the choice of instrumentation, tempo, and arrangement, concrete images and storylines in the minds and hearts of listeners. The titles of many tone poems further help the listener in that they acknowledge a composition’s roots in a famous legend, poem, picture, place, or historical event. A tone poem can conjure up visions of majestic mountains, forests, and waterways; knights on horseback gliding over desert sands; the appearance of magical beings, or the tender feelings between two lovers. And a favorite tone poem can make audiences feel transported, mentally and emotionally, to long-past heroic ages, or into the pages of beloved works of literature. Hungarian composer Franz Liszt is often credited with inventing the form of the tone poem, also known as the symphonic poem, in the mid-19th century. In this era of romanticism, revolution, and rising national consciousness, the form flourished. By the early 20th century, composers such as Igor Stravinsky were still writing richly orchestrated tone poems. However, the form began to shift toward using this type of colorful music as a background for dance performances, rather than as single-unit orchestral pieces. Here are brief summaries of what makes only a few of the best-known tone poems memorable: 1. The MoldauCzech composer Bedřich Smetana completed “The Moldau” after only 19 days of work in 1874. Since then, its central melody has become an iconic national symbol. The piece is one part of a six-section suite titled My Country, in which the deeply patriotic composer depicted the natural beauty and the rich cycle of history and myth of his native land. “Moldau” is the German name for the Vltava River, which flows from high forested mountains through the country lowlands and straight through the center of Prague. Smetana’s piece is by turns mystical, forceful, lively, and majestic, as it conjures up, first, the river’s quiet patter, then its sweep through a folksong-filled plain, to its destination near the capital, the royal seat of the Bohemian kings. 2. ScheherazadeRussian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov debuted his orchestral suite Scheherazade in 1888, offering audiences a collection of musical trips to the stories of the Arabian Nights. The deep, bold opening notes paint a powerful picture of Sultan Shahryar, and the sinuous lilt of the violin portrays his wife, the storyteller Scheherazade, with the later musical themes unfolding the stories she tells like the unrolling of a magic carpet. The four movements of the suite tell the story of Sinbad and his ship on the ocean; the “Tale of the Kalendar Prince,” bringing out the full capacity of the woodwinds to evoke an air of mystery; the tender and richly soulful romance of the story of a young prince and princess; and a finale that brings in themes from each of the previous sections, culminating in vivid images of a festival and the destruction of a ship on a wild, tempestuous sea. 3. FinlandiaIn 1899, Finnish composer Jean Sibelius composed and premiered his now world-famous tone poem “Finlandia” as part of a larger suite. Like Smetana, Sibelius was a patriot who used his music to challenge the rule of an empire over his small country. “Finlandia” was, in fact, originally written to be performed at an event protesting the Russian tsar’s censorship of the Finnish press. The work begins with the boom of timpani and brass to establish a somber and foreboding setting. As woodwinds and strings enter the musical conversation, they help to weave the type of stately atmosphere found in a king’s great hall. After a burst of forceful sound bringing in the sense of the whirlwind of struggle animating the Finnish people, the mood lifts. The piece concludes on drawn-out notes evoking a deep sense of serenity and majesty, as if listeners were looking down on sweeping vistas of dark-green Finnish forests. Soon after its composition, the central theme of “Finlandia” became popular worldwide, with many American communities using the melody for songs honoring cities, schools, and other organizations. 4. Fantasia Walt Disney’s 1940 full-length orchestral cartoon movie masterpiece Fantasia is a contemporary tone poem in itself. The film incorporates Disney’s retellings and re-imaginings of the stories behind several of the best-known symphonic works, including French composer Paul Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. In Disney’s version, Mickey Mouse is the hapless student of magic pursued by a pack of enchanted brooms.

Dukas’ original soundtrack debuted in 1897. He based it on a folkloric tale by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, one of the towering figures in the European literature of the Enlightenment. Dukas’ composition closely follows the sequence and spirit of Goethe’s piece by offering an opening that paints a picture of quiet, but magic-filled domesticity in the sorcerer’s workshop. But then the apprentice enters, represented by a leitmotif uniting oboe, flute, clarinet, and harp. A burst of timpani perhaps signals a stroke of enchantment. Then, through the composer’s use of a triple-time march, the sorcerer’s army of brooms comes lumbering, and then sprinting, to vivid life, carrying one bucket of water after another. Dukas masterfully uses strings to conjure up the flooding cascade of water that ensues before the sorcerer, accompanied by the gloomy moans of the bassoon, returns to chase away all the mischief. According to the National Association for Music Education, there are a few important qualities that make for an outstanding music teacher. These include strong communication skills, an understanding of how to make learning the rudiments of music worthwhile, the ability to command respect, and a capacity for forging emotional connections with students. Any list of the world’s notable music teachers throughout history would include the following talented individuals, who were also accomplished composers. Read on to learn about their lives, their music, and what they taught their students. Antonio Vivaldi – Leader of a girls’ orchestra Image by Wikipedia Image by Wikipedia By the time of his death in the mid-18th century, Italian composer and priest Antonio Vivaldi had authored hundreds of pieces of church music, concerti, operas, and other compositions. Best known today as the composer of The Four Seasons series of concerti, he exemplified the Baroque sensibility. His music is filled with complex, bravura passages that highlight the solo capabilities of individual instruments. Vivaldi was also a teacher, working at several different schools of music over his career. When he was just 25 years old, he became master of violin with the Ospedale della Pietà, a Venetian school for orphaned children. While serving in this capacity over some 30 years, he managed to compose the bulk of his major creative works. At the Ospedale, the boys were taught skilled trades, and the girls learned music. Vivaldi’s leadership of the girls’ orchestra and chorus brought international fame to the school. The group performed at religious services and often at special events intended to make an impression upon powerful visitors. The girls performed, however, concealed behind a set of gratings, supposedly for the purpose of safeguarding their modesty. Antonio Salieri – Villainous or defamed?Thanks in part to Milos Forman’s movie Amadeus, the dominant image of Antonio Salieri is a jealous villain who helped to drive his rival Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to an untimely death—or possibly poisoned him. But recent investigations have shown that there was likely far less substance to the feud between the two men. Newer biographies and recent performances and recordings of his music, including an album by Cecilia Bartoli, are beginning to show us that Salieri was a talented composer, with a personality that may have been cantankerous. Newer research also shows that he was viewed by contemporaries as a generally friendly, industrious, and occasionally even humorous man. Salieri’s creative output includes several operas in multiple languages, as well as chamber music and works for sacred occasions. Only six years Mozart’s senior, Salieri would live to the age of 74 and eventually see his powers as a composer dwindle, though he took on a roster of exceptionally gifted pupils. These included Ludwig van Beethoven, the German operatic composer Giacomo Meyerbeer, Franz Liszt, and Franz Schubert. Historians recount the story of how Salieri spotted the seven-year-old Schubert’s talent and began teaching him the basics of music theory. After Mozart’s death, Salieri even instructed Mozart’s young son. In 2015, a short composition created jointly by Mozart, Salieri, and a third composer was unearthed from the archives of the Czech Museum of Music. The following year, a harpsichordist in Prague gave the work its first public performance in 230 years. Nadia Boulanger – A “hidden figure” in music Image by Wikipedia Image by Wikipedia Nadia Boulanger earned international fame as a conductor and teacher of musical composition. Born in 1887, she was the daughter of Ernest Boulanger, a renowned voice teacher at the Paris Conservatory. She studied at the conservatory with composers Charles-Marie Widor and Gabriel Fauré, then began a career teaching both private lessons and classes. At age 21, she received a second place honor in the Prix de Rome competition for a cantata she had composed. Boulanger’s sister, who died young, was also a talented composer. In fact, after her sister’s death, Boulanger deemed her own work as a composer to be of no further use and stopped creating entirely. However, she continued to both promote her sister’s work and to teach others. By the early 1920s, she was working at the American Conservatory at Fontainebleau. Boulanger went on to become the first female conductor to work with the New York Philharmonic and other American orchestras. She taught in the Washington, DC area during the Second World War. In 1949, she earned the position of director of the American Conservatory. Boulanger’s first American student was Aaron Copland, and she later taught Virgil Thomson, Leonard Bernstein, Philip Glass, and a host of other noted composers. She lived to be 92 years old, but never in her long life wrote a textbook outlining her ideas on music theory. Rather, she exerted a strong and nurturing personal influence on her pupils. She worked to give them an in-depth understanding of the technicalities of music while enhancing their individual gifts of composition and expression. Zoltán Kodály – The centrality of the voiceZoltán Kodály, one of the best-known 20th century Hungarian composers, was also a scholar of the folk music of his country. Along with his contemporary Béla Bartók, he became one of the foremost collectors of traditional Hungarian songs. Kodály’s own creative compositions include the massive Psalmus Hungaricus, first performed in 1923 to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the joining of the cities Buda and Pest.

Kodály was also a contemporary of Boulanger and studied with Widor in Paris. He achieved renown for establishing the building blocks of what is today known as the Kodály Method, used by music teachers around the world. The Kodály Method works with the understanding that young children learn music best by doing, and that the body of traditional songs and dances of their own countries should form the core of their musical education, supplemented with the folk music of numerous other cultural traditions. Kodály’s system additionally puts great emphasis on the power and flexibility of the human voice as the first musical instrument. His method stresses singing as the best way to develop musical understanding and skill. Zoltán Kodály ranks among the foremost music educators of all time. He was born in what is now Hungary in 1882, and, well before his death in 1967, had earned an international reputation as a composer of highly original pieces, a scholar of folk music, and the originator of the method of music instruction that continues to bear his name. The Kodály Method has become widely known among music educators for its dynamic, interactive, and movement-oriented approach to instruction for children. It incorporates a set of proven techniques that foster the unfolding of a child’s natural gift for musicianship. The approach, which focuses on creativity and expressiveness, has demonstrated its relationship to the traditional ear-training method. During Kodály’s lifetime, his influence was felt throughout Europe and the world as an instructor who taught numerous teachers, and his method continues to be popular today. A young composer and teacher finds his vocation.In his youth, Kodály studied the piano, cello, and violin. When he was in his teens, his school orchestra performed several of his compositions. In 1900, he enrolled at the University of Sciences, located in Budapest, and became a student of contemporary languages and philosophy. He went on to study composition at Budapest University, but before graduating, he spent a year criss-crossing Hungary on a search for sources of traditional folk songs. He then centered his university thesis on the structural properties of Hungarian folk songs. Shortly after graduating in 1907, Kodály accepted a position in Budapest teaching the theory and composition of music at the Franz Liszt Academy of Music. He would remain on the school’s faculty for 34 years. Even after retiring, he returned to the school in 1945 to serve as a director. His dedication was driven by a desire to preserve his country’s musical culture, particularly in light of the unrest that characterized its political scene in his time. Before he entered into his duties at the Liszt Academy, Kodály met fellow Hungarian composer and folk music collector Béla Bartók. Together they published, over a span of 15 years, a folk song series based on their research. The series became the core of Hungary’s authoritative corpus of popular music. A 20th century master of styles.Kodály’s own style as a composer was anchored in the folk music that he loved and had a richly Romantic tone, while incorporating classical, modernist, and impressionistic techniques, as well. His best-known works include a concerto for orchestra, chamber pieces, a comic opera, groups of Hungarian dances, and the 1923 work Psalmus Hungaricus, which was created to honor the 50-year anniversary of the fusion of Buda and Pest into a single city. The piece brought him international fame and conferred upon him the mantle of musical spokesman for the culture of his country. As both a scholarly writer and musician, Kodály in his later years penned numerous books and articles on Hungarian folk songs. An evolving method.One story, perhaps apocryphal, has it that Kodály was so disappointed when he heard a group of schoolchildren perform a traditional song that he decided to improve the state of Hungarian music instruction himself. Kodály put nearly as much emphasis on developing his music education program as on his own creative works of composition. His interest in the issue of music teaching was intense, and he produced a variety of educational publications designed to expand the horizons of teachers. Kodály thought that music was among the vital subjects that should be required in all systems of primary instruction. He further stipulated that it be presented in a sequential framework, with one step logically leading to the next. He believed that students should enjoy learning music, that the human voice is the premier musical instrument, and that the most accessible teaching method incorporates folk songs in a child’s original language. Kodály himself was primarily the originator of his eponymous method, generating numerous ideas and principles that now form the basis of its core teachings, as used in classrooms today. However, it was left to the Hungarian teachers that he trained and inspired to fully develop it over time, often under his direct guidance. The Kodály Method serves as a comprehensive system of training musicians in the reading and writing of musical notation, as well as the acquisition of basic skills. In doing so, it draws upon proven techniques in the field of music instruction. It is also in itself a philosophy of musical development that emphasizes the experiences of each learner. The importance of the human voice. One of the basic principles of the method is singing, which Kodály himself viewed as the core of his system. The Kodály Method stresses that, first, a child should learn to love music for the sheer fact that it is a sound made by other human beings, and one that makes life richer and happier. Teachers of the method also emphasize the human voice as the one musical instrument accessible to most people around the world as a common means of expression. One reason why singing has such a central role in the method is the idea that the music one creates by oneself is better retained and provides a greater feeling of pride and personal accomplishment. The Kodály Method therefore places singing—and reading music—ahead of any sort of training on an instrument. Kodály also believed that singing was the best means of training the inner musical ear. The content of any classroom based on the Kodály Method will consist largely of folk songs from a child’s own heritage, as well as those of other cultures. Classic childhood rhymes and games will also be included, as will pieces of great music produced in any time and place. Continuing the work. Since 2005, the Liszt Academy has hosted the Kodály Institute, which provides advanced-level music education training for teachers, based on the Kodály Method. The institute works as the guiding force for the entire set of music instruction programs of the academy. In addition to its teacher-training programs, the institute offers the International Kodály Seminar every two years. Participation in the seminar is open to music teachers around the world and coincides with an international festival of music. The next seminar is scheduled to take place in July 2019. For more information, visit Kodaly.hu.

Learning to play the piano is the beginning of a great adventure for young children, who will make many musical discoveries that will enrich their lives. Some may go on to make music a career, and they will always remember their first exercises at the keyboard. For generations, parents, experts, and educators have recommended simple pieces of piano music from the classical keyboard repertoire that are the most suitable for these early learners. Those on this list are a few of the most often recommended, both for their innate beauty and their value as learning tools. 1. Ludwig van Beethoven: Für EliseThe short piece “Für Elise” (“For Elise”) is one of the most instantly recognizable of the world’s simplest piano compositions. Listed in the Beethoven catalog as “Bagatelle No. 25 in A minor,” for the youngest students it is anything but a frivolous throwaway piece. Educators often suggest it as a practice piece based on its clear melodic line and pleasing harmonics. Beethoven’s original manuscript for this piece likely does not refer to an “Elise.” Some scholars believe that the obscured first title read “Für Therese” (possibly referring to a young woman who spurned the composer’s marriage proposal). “Elise” may have come about as the result of a transcription error. 2. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Sonata No. 16 in C MajorMozart’s Sonata No. 16, known as “Sonata semplice,” or “Sonata facile,” is only “facile” because it is easy for beginners to play. He created it as a solo piece just for young beginners at the piano. It is a perennial favorite because it affords them the chance to perform a piece by this notoriously difficult composer with confidence. The catchy melody and easy progression of the musical parts of this composition make it relatively simple to understand and to perfect for beginners. In performance, it typically takes about 14 minutes total. 3. Johann Sebastian Bach: Minuet in G MajorBach’s wife, Anna Magdalena, left behind a notebook that contained this short harpsichord piece, which she had carefully hand-copied. Her notebook consisted of pieces by major composers of her time and before, a list that naturally included her husband. But some scholars today attribute this particularly lovely little piece not to Bach, but to fellow composer Christian Petzold. Whoever the original composer may have been, Minuet in G remains a favorite of students and their teachers. It immediately leaps out of the air with a sprightly beginning, offers simple and easily distinguished variations, and ends with a sweet and definitive conclusion. 4. Robert Schumann: “Einsame Blumen”In the original German, “Einsame Blumen” means “Lonely Flowers.” Schumann wrote this simple, melodic piece for his wife, Clara. She was also a distinguished pianist and performer. The piece is part of the larger Schumann collection of piano miniature compositions entitled Waldszenen (“Forest Scenes”), Op. 82. Each one is a small tone poem that, in loving detail, offers an image of wilderness romanticism. “Einsame Blumen” is an excellent choice as a teaching vehicle for young beginners. Additionally, it remains a staple of the concert repertoire due to its soft, soothing quality and its gentle musical transitions. 5. Frédéric Chopin: Prelude in E Minor, Op. 28, No. 4Chopin was a virtuoso pianist, but he composed a number of pieces that are easy enough for young beginners. These include the haunting, simple melody and spare harmonies of this Prelude in E Minor. Music teachers often recommend that students new to Chopin start with learning his preludes, as they are the simplest and most accessible part of his oeuvre. This particular prelude is typically considered among the easiest piano pieces for a beginner to execute. This is due in part to its easy, distinctive melodic line for the right hand, accompanied by the series of basic chords for the left. 6. Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: “Italian Song”Tchaikovsky was not himself particularly known as a virtuoso of the piano. His collection in Op. 39, “Album for the Young,” reflects his focus on teaching young beginners through relatively simple compositions. “Italian Song” is perhaps the best-known of these, offering a lively, lilting, picturesque melody with a strong through-line. Other compositions in “Album for the Young” are even simpler: “The Sick Doll” and “Morning Prayer” are typically ranked by music educators as highly suitable for young beginners. Other pieces in the collection are somewhat more difficult, and are perhaps better adapted for the needs of more skilled players. 7. Erik Satie: Gymnopédie No. 1Satie, well-known as an early 20th century avant-garde French composer, created his series of “Gymnopédies” in 1888. They have stood the test of time among the simplest and loveliest beginning piano melodies. Additionally, the fact that they are meant to be played at slow tempos enhances their value to the youngest students. Today, Gymnopédie No. 1 is instantly recognizable from its frequent use in film and television as a slow-paced mood piece. In fact, a number of critics have cited it as one of the most relaxing pieces to have ever been composed. The Juilliard School, which is housed at the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts on New York City’s Upper East Side, is an educational institution that has helped to further the skills, talents, and careers of numerous young musicians and other performing artists from around the world for generations. Over the years, The Juilliard School has expanded its programs to include a broad array of performing arts curricula, and it now serves as Lincoln Center’s professional education division. It offers undergraduate degrees in music, drama, and dance, as well as a master’s program in music. Its current total enrollment stands at approximately 1,400 students. The following are a few interesting facts about the Juilliard School: 1. Distinguished alumniDesigned as a place to nurture extraordinary talent, The Juilliard School has produced scores of distinguished graduates who include legendary pianist Van Cliburn; cellist Yo-Yo Ma; conductor Leonard Slatkin; contemporary actors Viola Davis, Jessica Chastain, Samira Wiley, and Michael Urie; and Jon Batiste, bandleader on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert. 2. A turn-of-the-century American conservatoryThe school began as the Institute of Musical Art in 1905, when it took up residence at the corner of 12th Street and Fifth Avenue. Founder Dr. Frank Damrosch was the godson of the 19th century composer and musical prodigy Franz Liszt. Damrosch, then the head of the city’s music education program for public schools, worked with a focus on providing American music students with access to the same quality of instruction that was common in the best European conservatories. When the institute opened its doors, it did so with a student body that was five times as large as originally expected, leading to a sudden need for expanded quarters. In 1910, it relocated to a space close to Columbia University. 3. A benefactor’s legacyIn 1919, Augustus Juilliard died, leaving a will containing the largest single bequest to further music education that was unseen up until then. Juilliard, who made his fortune in the textile industry, was thus immortalized in 1924 through a new institution called The Juilliard Graduate School, funded by his bequest under the auspices of the Juilliard Foundation. Two years later, the graduate school merged with the Institute of Musical Art. The new combined school would be renamed The Juilliard School of Music in 1946. 4. Expansion beyond musicThe school, as constituted after 1926, came under the direction of a single president, John Erskine, a popular novelist and a professor at Columbia University. In 1937, Ernest Hutcheson, a widely known composer and pianist, took over as president, followed in 1945 by William Schuman, a distinguished composer. Schuman began an effort to increase the school’s reach by offering not only music courses, but a new dance division, as well. The Literature and Materials of Music program, a pioneering curriculum in the art of music theory, also became a core component of the school during his tenure.  Image courtesy Shinya Suzuki | Flickr 5. An iconic string quartetIt was also under Schuman’s direction that the school established its own in-house quartet, the Juilliard String Quartet, in 1946. The Boston Globe has called the quartet the most important ensemble of its kind ever to be founded in the United States. Today, its members not only champion and exemplify the classical tradition, but they consistently work to expand the repertoire of newer works performed. Its 2018-19 season features works that include a newly commissioned piece by renowned Estonian-American composer Lembit Beecher. Quartet members served as master instructors during their touring seasons, working with students in classes and open rehearsal formats. The group also hosts a five-day-long Juilliard String Quartet Seminar, annually in May. In 2011, the quartet received a National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences lifetime achievement award, the first ever presented to a classical ensemble. The Juilliard School today also hosts a broad array of other performances, including those by its orchestra, wind ensemble, and members of its Marcus Institute for Vocal Arts. 6. Becoming part of Lincoln CenterIn 1968, when Peter Mennin served as Juilliard’s president, he oversaw the creation of a drama studies program headed by powerhouse actor and producer John Houseman. In that same year, under Mennin’s direction, the school rebranded itself with its current name, The Juilliard School, then relocated to its campus to Lincoln Center in 1969. During Dr. Joseph W. Polisi’s tenure as president, Juilliard added new curricula in historical performance and jazz, as well as several new drama and liberal arts tracks and community engagement programs. Damian Woetzel, a former principal dancer with the New York City Ballet, became Juilliard’s president in the summer of 2017. 7. A rich history captured on filmA documentary on the history of the school, which was produced by PBS, features the remembrances of current and former alumni and instructors. In 2018, the documentary became available for streaming online. Titled Treasures of New York: The Juilliard School, the hour-long film includes comments from world-renowned figures in the arts such as violinist Itzhak Perlman and trumpeter and music educator Wynton Marsalis. The film captures the school’s rich history of teaching, learning, and performing, from its inception to its relocation to Lincoln Center. 8. An even stronger international footprintThe Tianjin Juilliard School in China is projected to open in the fall of 2019. The school’s creators envision it as incorporating all of the elements of a true 21st century music conservatory on an international scale.

Sergei Prokofiev | Image courtesy Wikipedia Sergei Prokofiev | Image courtesy Wikipedia In 1936, shortly after returning to the Soviet Union after living in Europe for 18 years, composer Sergei Prokofiev created one of the world’s most memorable and enduring musical pieces: Peter and the Wolf. Ever since, Peter and the Wolf has entertained children while educating them about the sounds of key orchestral instruments. Here are a few notes on Peter, the Wolf, their creator, and how this charming suite continues to be adapted to the needs of today’s music students: An instrument defines each characterIn Prokofiev’s story, every character has a signature instrument and tune that define individual personality. Music teachers can help children learn to identify the four families of instruments the composer used in the piece: strings, woodwinds, brass, and percussion. Peter is portrayed by a joyous leitmotiv from a string quartet. Peter’s animal friends are the bird, portrayed by a lilting trill on the flute; the duck, depicted through the waddling gait of the oboe; and the cat, who slinks through the story accompanied by the lower registers of the clarinet. The chugging of the bassoon portrays Peter’s stern and scolding grandfather, and the rolling kettledrums bring a group of hunters to life. A series of sinister blasts on three French horns conveys the menace of the wolf. A rollicking, melody-filled adventure storyIn Prokofiev’s original plot, Peter is a Communist Young Pioneer who lives in the forest at the home of his grandfather. When Peter is walking through the forest, he encounters his friend the bird flying through the trees, the duck swimming, and the cat stalking the birds. Peter’s grandfather comes out of the house to warn his grandson about the dangerous wolf that lurks in the forest, but Peter has no fear. The wolf eventually comes slinking past Peter’s cottage and devours the duck. So Peter avenges his friend and captures the wolf. He struggles with his captive but ends up tying him to a tree. The hunters appear, wanting to kill the wolf, but Peter persuades them to take the wild creature to the zoo, borne along in a celebratory parade. Peter and the Wolf earned quick success and is still beloved today by children, teachers, and parents. Prokofiev called on his memories of his own childhood for scenes and characters. A composer’s life in light and shadowsBorn in 1891 in what is now Ukraine, Sergei Prokofiev learned to play the piano as a child. When he grew older, his mother moved with him to St. Petersburg so that he might continue his studies with instruction at a higher level. He began his formal studies at the St. Petersburg Conservatory and became a skilled pianist, composer, and conductor. As a young man, Prokofiev became a dedicated traveler, intent on soaking up a variety of musical styles on visits throughout Europe and even to the United States. After the devastations of the Russian Revolution and the First World War, he settled in Paris, but he missed his homeland so much that he returned to the Soviet Union in 1936. He composed Peter and the Wolf for the Moscow Central Children’s Theatre that same year. As his career blossomed, Prokofiev studied artistic influences including Igor Stravinsky, ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev, and modernist artists such as Picasso. His oeuvre includes compositions for opera, ballet, and film. His symphonies and his concertos for piano, cello, and violin are notable among his works, as are his ballet Romeo and Juliet and his music for Sergei Eisenstein’s revered film Alexander Nevsky. As the Cold War began, Soviet authorities targeted the composer for exclusion from cultural life due to his supposed anti-traditionalist point of view. Because the United States feared Soviet aggression, Western audiences also cooled toward him. When he died in 1953—on the same day as dictator Joseph Stalin—few newspaper readers noticed. Disney works its magic on the storyThere have been numerous recordings of Peter and the Wolf since its debut. The most famous film version is undoubtedly the Walt Disney company’s animated short subject in full color. This film was presented as part of the 1946 feature-length compilation Make Mine Music, which included a variety of other cartoon shorts focused on making music education fun. In the Disney version, the animals have names and distinct personalities: The bird is named Sasha, the duck Sonia, and the cat Ivan, and each character livens things up through comedic routines. A beloved favorite in schools and theatersDozens of lesson plans about Peter and the Wolf have been created for students of all ages. Typical of these is one created for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. In this program, students hear the story, then listen to musical excerpts to become familiar with individual characters and their accompanying instruments. This goal is to ensure that students will understand the storyline; be able to pick out each character’s musical motif and signature instrument; anticipate how each theme will sound in the composition; and identify individual instruments, as well as instrument families, by sound and tone color.

Local companies continue to stage imaginative productions of Peter and the Wolf as part of campaigns for music education. For example, Seattle Children’s Theatre put on a local playwright’s adaptation of the story in which an Emmy Award-winning musician recast Prokofiev’s classic musical motifs with contemporary music styles such as the Charleston, the tango, and the two-step shuffle. The creative team enhanced the production with puppetry, movement, and an expanded series of humorous incidents. Unfortunately, there is no evidence to support the widely-held idea that exposing infants and children to classical music can lead to an increase in their intelligence. However, research does indicate that listening to classical music can have a positive effect on many other areas of children's development. Recent studies have suggested that young children who are exposed to classical music find it easier to concentrate, develop a stronger sense of self-discipline, are better listeners, and ultimately have a wider range of interest in music as they grow into young adults. If you’re interested in introducing your child to classical music, these five popular and powerful pieces written by some of the greatest composers in history are an excellent place to get started. 1. Eine kleine Nachtmusik, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

2. The Flight of the Bumblebee, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov

3. Fur Elise, Ludwig von Beethoven

4. The Nutcracker Suite Op. 71a, Pytor Ilyich Tchaikovsky

5. Clair de Lune, Claude Debussy

Though most music fans have a favorite genre of music, there are many benefits to listening to music styles from cultures unlike your own. Listening to music from different countries, even when performed in a language that you don’t understand, can help expand your perception of the world, bridge gaps between cultures, and even introduce you to a new favorite music style that you may not have otherwise discovered. For those interested in learning about music outside of the western world, check out the following five international music styles that are widely enjoyed on other continents. K-PopAlready massively popular in its home country of South Korea, K-pop music has steadily gained a dedicated international fan base in recent years, including in parts of Europe, the Middle East, South America, and the United States. This upbeat music style is a blend of hip-hop, pop, and electronic music and is characterized by family-friendly lyrics with song hooks written to be blatantly catchy. K-pop music is almost always performed by all-female or all-male-fronted bands who release exciting, big budget music videos featuring extensive choreography and colorful, fashion-forward costumes. One of the first K-pop songs to receive widespread radio play in western countries was the song “Gangnam Style” by the artist PSY, who released the hit tune in 2012. CalypsoCalypso music is native to the Caribbean islands and most prominently performed in Trinidad. First developed in the early years of the 20th century, Calypso is influenced by both West African rhythm and European folk music. It relies heavily on stringed instruments like the guitar and banjo combined with steady percussion from instruments such as maracas or tamboo-bamboos. The lyrics of Calypso songs originally served as a way of spreading current events throughout the island of Trinidad in the early 1900s, especially news that was political in nature. However, the political climate at the time that Calypso music was first established required musicians to deliver the divisive subject matter through carefully-constructed lyrics that were typically witty and rooted in satire. This lyrical tradition continues in the genre today. Though not technically a Calypso musician, the singer Harry Belafonte helped popularize the genre through the release of “Banana Boat Song (Day-O)” in 1956. QawwaliThe origins of qawwali date back more than 700 years to India and the south of Pakistan. Usually performed by Sufi Muslim men, the music is a tool through which the musicians, known as qawwals, can inspire congregations. It is a powerful form of music that incorporates poetic lyrics and percussive instruments like the harmonium, tabla, and dholak to move its listeners to a state of heightened spiritual union with God, or Allah. The typical qawwali ensembles includes one singer or pair of lead singers accompanied by a chorus of individuals who sing the song’s refrains and support the percussion with rhythmic hand-clapping. Though it remains predominantly religious in nature, the style has expanded beyond the devout Sufi demographic, in a manner similar to Gospel music in the United States. The late musician Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan is considered to be the individual responsible for expanding the popularity of qawwali outside of its traditional roots. RaïA style developed in the northern African country of Algeria, raï combines popular western-style music with that of the nomadic desert-dwelling people known as the Bedouins. While early versions of this musical style incorporated flutes and hand drums, the modern iteration of the genre is heavily influenced by pop and dance music and features a wide range of instruments, from saxophones and trumpets to drum synthesizers and electric guitars. One thing that has remained unchanged about raï music from its inception through modern day is the blunt nature of its lyrics, which are sung in Arabic or French. Song lyrics address the ups and downs of everyday life in a direct and occasionally vulgar fashion, and singers sometimes improvise during performances in the way of American blues musicians. The most famous raï singer of today is a performer named Khaled, who is commonly known as “the King of Raï.” Funk CariocaKnown alternatively as baile funk, funk carioca is a beat-heavy music style that developed in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in the 1980s. By bringing American funk music, hip-hop, and freestyle rap music together and combining them with older Brazilian songs, DJs in Rio de Janeiro created a new genre that became ideal for dancing and popular among the country’s youth. Lyrics in funk carioca music are known for addressing taboo subjects, including poverty, social injustice, sex, and the violence occurring within Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, or shantytowns. The melody of funk carioca songs is typically sampled from an older tune, and may be instrumental or feature rapping and/or singing, often in Portuguese. One of the more popular funk carioca-inspired artists to find success outside of the original fan base in Rio is the rapper M.I.A., who is not Brazilian but is heavily influenced by the style, as evidenced by many songs on her 2005 album Arular. Though film is primarily thought of as a medium for telling a story through acting, music plays a significant role in the way that movies affect their viewers. One gratifying music industry profession is that of a film composer - a professional responsible for captivating audiences through sound and adding a deeper element to the emotions that viewers experience as they watch a story unfold on screen. Listed below are five modern film composers who stand out by doing exactly that. 1. John WilliamsJohn Williams’ work as a composer has included some of the most iconic scores in the history of film. Born in New York City in 1932, Williams is a Julliard-trained jazz pianist who worked as a movie studio musician before pursuing a career as a film composer. Over the course of 50 years, he has written music for over 100 movies, with some of the most notable being Jaws, the Indiana Jones films, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Jurassic Park, Home Alone, and the Star Wars films. He has been nominated for 50 Academy Awards, of which he won five, for the movies Fiddler on the Roof, Jaws, Star Wars, E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, and Schindler’s List. Arguably the most famous modern American film composer today, Williams’ style is identifiable by his loyalty to full-bodied symphonic music in an age when synthesizers and electronic elements are more popular than ever. 2. Danny ElfmanA musician who never received formal musical training, Danny Elfman began his career by composing the score for his brother Richard’s film, The Forbidden Zone. Prior to embarking on his career in music composition, Elfman studied the musical styles of African countries, particularly Mali and Ghana. His exuberant melodies and quirky style caught the attention of eccentric director Tim Burton in the mid-1980s, with whom he first collaborated when he developed the score for the movie Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, which starred Paul Reubens. This led to further work writing music for all but two of Burton’s films, including Beetlejuice, Batman, The Nightmare Before Christmas, Sleepy Hollow, and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. His composition style is influenced by an early exposure to jazz, classical, blues, pop, and international music. Though he’s known for his unconventionality, he also has shown himself to be adept at developing more classical scores. His more classically-influenced scores can be seen in his contributions to Academy Award-winning movies like Good Will Hunting, Silver Linings Playbook, and Milk. 3. Hans ZimmerLike the aforementioned Danny Elfman, legendary German-born composer Hans Zimmer did not receive any early formal instruction in music. The self-taught musician was particularly drawn to the electronic synthesizer and piano as a young man. He began his career in music as keyboardist for a band named The Buggles, famously known as the group behind the first music video ever featured on MTV, “Video Killed the Radio Star.” His first work in film was with the director Stanley Myers, with whom he founded a recording studio in London in the 1980s. After working on various critically-acclaimed movie scores, he received his first Academy Award nomination in 1988 for composing the score to Rain Man, starring Tom Cruise and Dustin Hoffman. Since this first nomination, Zimmer has received an additional eight Academy Award nods, with one win for his work as composer of The Lion King soundtrack. He has also written the score for blockbuster films such as Interstellar, Inception, Sherlock Holmes, The Last Samurai, and Gladiator. Most experts in the industry describe his style as an innovative hybrid of musical genres, with a heavy rock and roll influence. 4. Thomas NewmanFor Thomas Newman, becoming a film composer was seemingly a birthright; his father was nine-time Academy Award-winning composer Alfred Newman, the man behind the sound of iconic 20th-century films like The King and I, The Mark of Zorro, and The Greatest Story Ever Told. Thomas Newman took lessons in piano and violin as a child, and would later go on to receive his masters in music from Yale University. He earned his first major Hollywood film position supporting John Williams as he recorded the score for the Star Wars film Return of the Jedi. After regular work as a film composer in his own right for the rest of the 1980s, Newman earned the first of 14 current Academy Award nominations for the music he wrote for The Shawshank Redemption. He has since worked as a composer on a wide range of films, including dramas like American Beauty and Road to Perdition as well as family films like Finding Nemo, WALL-E, and Saving Mr. Banks. Additionally, he wrote the score for the Sam Mendes-helmed James Bond movie Skyfall. Newman’s compositional style is considered bold and diverse, with heavy rhythms made up of sweeping orchestral music combined with electronic elements as well as solo piano. 5. Ennio MorriconeThe most prolific and experienced of all composers on this list, Italian composer Ennio Morricone is, in the opinion of film music historians, singlehandedly responsible for the invention of the musical style that characterizes classic American western films. Having worked on over 500 films in his six-decade career, Morricone is a versatile composer who has created music in nearly every genre. However, his legacy as the creator of the “spaghetti western” sound is the one that changed film history. He studied music in Rome as a child, worked as a jazz trumpeter as a young man, and eventually teamed up with director Sergio Leone to create the scores for the Clint Eastwood films A Fistful of Dollars; The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly; and Once Upon a Time in the West. One of his most recent notable works in contemporary western film was the 2015 Quentin Tarantino movie The Hateful Eight, for which he won the first Oscar of his career.

His strength as a composer lies in his ability to combine diverse instruments and styles into a single piece, drawing from a wide range of genres, including jazz, avant-garde, Italian, rock, and electronic music. |

Photo used under Creative Commons from Marina K Caprara

RSS Feed

RSS Feed