|

Music therapy has long been recognized as a way to help patients heal from trauma. Music-focused therapy offers multiple benefits: it can foster positive social relationships, reduce feelings of anxiety, modulate the intensity of emotionally fraught memories, and bring about emotional catharsis as patients work through painful events. Music therapists have assisted people who have experienced some of the most terrifying natural disasters and terror attacks in recent history. For instance, therapists have brought the healing powers of music to survivors of 9/11, Hurricane Katrina in 2005, mass shootings, and war and conflict zones around the world. A tested healing profession The American Music Therapy Association (AMTA) offers a concise definition of its field: Music therapy is anchored in clinically verified and evidence-based practices designed to help patients achieve their therapeutic goals in collaboration with professionals credentialed through an approved music therapy program. A professional qualified in music therapy can assist clients in a variety of settings, including private practice, public hospitals, mental health clinics, substance abuse treatment facilities, and more. A century-old treatment for trauma Music therapy as a means of healing after trauma first gained currency in the United States after American physicians began treating soldiers who developed post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) during service in the First World War. Today, music therapy and its practitioners are part of a well-established medical and psychiatric tradition. Building multiple types of resilienceMusic therapy is not a “cure” for the aftermath of trauma, but it can help patients of all ages strengthen their understanding of their emotions and acquire positive skills for coping with long-term symptoms. The AMTA’s principal findings on the efficacy of music therapy note that it can be effective in strengthening patients’ ability to function successfully in terms of their emotions, reasoning capacity, relationships, and overall behavior. When successfully practiced, music therapy can also ease muscle tension, and it can be conducive to promoting greater relaxation and increased openness in interpersonal relationships. Going where words cannot For people who have experienced trauma, music can provide a deeply important means of communicating what they urgently need to express—without words. Music therapists often point out that their patients need to be reassured that the often-overpowering emotions they may feel in response to trauma are normal and valid. Patients also sometimes need “permission” to explore what are often threatening or negative emotions surrounding the events of their trauma, in a safe environment. Music therapy has shown the ability to provide a wordless way for patients to express fraught or uncomfortable emotions about traumatic experiences. The non-invasive, non-judgmental aspect of music therapy is particularly important to note here. Patients can pour their feelings into listening to or performing highly expressive, artistic creations without fear of the negative reactions or judgments of others. While talk therapies are often very helpful to patients, experts point out that music therapy offers the advantage of providing clients with a quick resource for tapping into previously ignored or threatening feelings and memories. In certain instances, music therapy has even been shown to lead to shorter inpatient stays and a better fulfillment of clients' larger goals for treatment. Increasing confidence and control Music therapy can also help patients to feel more in control of their own emotions and can give their self-confidence and feeling of personal empowerment a much-needed boost. For people who have undergone traumatic experiences, this is especially needed. Many people who have been traumatized feel confused, bewildered, and powerless. They may feel as though life has become chaotic and that nothing—and no one—can be trusted. Healing relationshipsIn addition, music therapy can assist people in reconnecting with their loved ones in positive ways, reestablishing bonds of intimacy that may have been strained or broken under the strain of the trauma. Easing stressStress reduction is perhaps one of the most meaningful and most studied benefits of music therapy. According to the American Psychological Association, a study of pre-term babies in a neonatal intensive care unit suggested that lullabies may have the power to soothe infants and their parents, who find themselves in the midst of a bewildering array of medically necessary, but intrusive and noisy machinery. The researchers in this 2013 study also surmised that the soothing music might have the ability to regulate the babies’ sleep habits.

Interestingly, of all the methods of delivering the music to the babies, singing was the most effective at slowing their heart rates and lengthening the amount of time they remained in a state of calm alertness. According to the study’s lead author, live music in particular shows the most potential to appropriately stimulate and activate the human body, elevate a patient’s quality of life, and promote recovery. Choral music has held a revered and beloved place in human societies since the beginning of recorded history. From medieval times to today’s children’s choirs, here are four things you need to know about choral music: 1. Choral music has its roots in religious music.Most of today’s choral singing groups can trace the roots of their practices back to sacred music. The most popular example is probably the Gregorian chant that was a familiar part of medieval church services. In Gregorian chant, groups of monks would participate together in singing the various passages of sacred music. The conscious blending of their individual voices created the powerful sound of a single musical presence. It still serves as the model for much modern-day choral music. Gregorian chant, a form of the monophonic “plainsong” or “plain chant,” accompanied the recitation of the mass and the divine office of the canonical hours. It derives its name from the fact that it developed during the rule of Pope (later Saint) Gregory I, at the turn of the 7th century of the Common Era. The development of polyphony, the use of more than one voice or tone heard in a composition, brought composers the opportunity to expand on the range and types of compositions they wrote. When creating contrasting vocal parts, composers often drew on the talents of young boy sopranos to sing the contrasting trouble notes. This is because during this period in history, women’s voices were often forbidden in public performance. 2. Choral music eventually found a secular audience and begin to include lyrics and instruments. As religious reformation and social secularization progressed, audiences outside sacred spaces enjoyed greater opportunities to hear choral music in performance. Once it flowed outside the monasteries and into the streets, its composers experienced greater creative freedom. They began to abandon the formalized structures common to sacred choral music, and to add instruments into the mix. Composers also began to bring in human voices singing in chorus to enhance and add texture to familiar types of instrumental pieces. The addition of words enabled composers of instrumental music to address their audiences in new ways. The Baroque period saw Italian composer and singer Claudio Monteverdi creating “polychoral” sacred pieces with multiple choirs and increasing numbers of instruments. The 16th and 17th century choral tradition also included the development of numerous motets, a form that evolved during the Middle Ages into a variety of types of religious and secular compositions. 3. Choral music was integrated into the oratorio and symphonic traditions.The oratorio, a larger composition for orchestra, chorus, and soloists and typically based on stories from scripture, was born as composers expanded on the form of the motet. The oratorio form reached its apogee during the 1600s. The German composer George Frideric Handel, who worked extensively in England, perfected this type of music. Handel became, in fact, the father of the particularly English style of oratorio. One exceptional 19th-century example of the integration of choral music into the symphony is the “Ode to Joy” sequence of the 1824 Ninth Symphony of Ludwig van Beethoven. The large-scale choir’s singing of text by the lyric poet Friedrich Schiller lifts the mood into a soaring affirmation of humanity’s potential. For many lovers of classical music, Gustav Mahler’s use of choral performance in his titanic symphonies represents the pinnacle of the form. Mahler’s Second “Resurrection” Symphony, as well as his Third and his Eighth, offer powerful musical interpretations of the nature of love, life, and fate enhanced by the voices of their choruses. The Austrian composer, whose creative period straddled the 19th and 20th centuries, became known for his thundering, multi-layered sound. His Eighth Symphony earned the title of “Symphony of a Thousand” thanks to its gargantuan cast of voices and instruments. It is written for performance by a massive orchestra, a double chorus, a boys’ choir, and eight single solo voices. 4. Today, children's choral groups continue to delight performers and audience members alike.Today, choral music in the United States continues to flourish, performed by a wide range of ensembles of all ages. Children’s choruses offer opportunities for young people to engage with music education, learn performance skills, and develop friendships based on a common commitment to creative work.

The Children’s Chorus of Washington is one group that represents the nation’s capital. Over the past 24 years, it has provided choral training and experiences to 2,500 youth and toured internationally. The Children’s Chorus of Greater Dallas is a mosaic of six individual groups of some 450 singers total. Under the auspices of the Deloitte Concert Series, it performs seasonal concerts at the Morton H. Meyerson Symphony Center. The Boston Children’s Chorus is composed of about 500 students from all over the greater Boston area. Almost half of them live in the city of Boston. Children’s choruses typically hold auditions at designated times of year, and work hard to open opportunities to as many talented young people as possible. The BCC’s students, like those in Washington DC, Dallas, and many more communities around the country, are eligible to receive need-based scholarships to support their participation. In fact, about 80 percent of the BCC’s performers attend its musicianship programs on scholarship. Teaching children to sing and play their country's national anthem—and those of other nations—can be a fun, effective musical lesson. National anthems can also serve as an effective means of connection between the arts and studies in geography and culture, at a time when educators are realizing the value of helping students build bridges between subjects. Enriching the music curriculum through cultural geographyIn units on patriotic songs, teachers have come up with rich curricula on the US national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner,” and many other national anthems. Information on some of these is available through the National Association for Music Education (NAfME). The organization offers links to repositories of vocal and instrumental performances of these anthems, as well as sheet music and background summaries on hundreds of current and historic anthems. In addition, several publishers offer engaging books for children explaining the origins and importance of national anthems. Also widely available are books for all ages containing sheet music of the world’s anthems. The book National Anthems from Around the World, prepared by well-known music publisher Hal Leonard, LLC, is just one example. Thanks to the internet, recordings of these anthems in their original languages are only a few clicks away. Several versions are accessible on YouTube and Spotify. Public libraries are another rich—and free—source for streaming versions of the world’s national anthems. Music is a truly universal language. On the other hand, a country’s national anthem presents its people’s viewpoint on their history and their hopes for the future. Let's take a look at a few contemporary national anthems and learn how the stories they tell demonstrate both the diversity and common experiences of the world’s peoples. A poignant reflection on warWhile it's notoriously difficult to sing well, “The Star-Spangled Banner” had become a time-tested American institution even before it became the country’s official anthem in 1931. President Herbert Hoover signed the congressional resolution declaring the song’s historic status on March 3 of that year. Francis Scott Key famously wrote the words as a poem on September 14, 1814. Key drew inspiration from his sighting of a single American flag still flying over Fort McHenry in Maryland as the fort sustained British bombardment during the War of 1812. Key was an eyewitness to the attack, as he waited on board a ship only a few miles away with the friend he had just helped release from British captivity. Key titled his poem the “Defence of Fort McHenry.” Years later, others set his words to the tune of the English drinking song “To Anacreon in Heaven,” composed by John Stafford Smith. A royal and national hymn that went around the worldThe country from which the United States gained its independence has its own time-honored anthem in “God Save the Queen” (sung as “God Save the King” during the reign of a male monarch). This anthem is also often used throughout the British Commonwealth. The song’s origins are obscure. The Oxford Companion to Music lists several early variants. Some authorities credit Henry Purcell or any of several other 17th century composers. Many music historians cite composer and keyboardist John Bull, who died in 1628, as the song’s likely author. Others point to a passage in an old Scottish carol as remarkably similar to the current version of the anthem. In any case, the earliest known printing of the unattributed lyrics to “God Save the Queen” appeared in 1745. The song soon appeared on the English stage and found its way into the work of composers George Frideric Handel and Ludwig van Beethoven. American composer Samuel F. Smith borrowed the tune for “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee,” which appeared in 1832 and has become an unofficial second national anthem for the US. A paean to the “True North”Canada’s national anthem, “O Canada,” was first publicly performed in 1880. Its title in the original French, as written by Sir Adolphe-Basile Routhier to music by Calixa Lavallée, was “Chant national.” A special government committee approved the song as the country’s national anthem in 1967, and it was officially adopted in 1980. The song’s lyrics celebrate the beauty and strength of this country of the “True North,” and express the hope that, through the help of God and “patriots,” it will remain “glorious and free.” Born in revolutionFrance’s national anthem, the marching song “La Marseillaise,” literally calls citizens to arms in defense of freedom in the fight against tyranny. Amateur composer Claude-Joseph Rouget de Lisle came up with the song overnight in 1792, at the height of the revolution that overthrew the French monarchy. The song’s current popular name arose after troops from the port city of Marseille adopted it as a particular favorite. The beauty of the landSome national anthems focus less on military or sovereign power and more on the natural beauties of the lands they represent. Australia’s national anthem, “Advance Australia Fair,” exalts its people’s home “girt by sea,” with its “beauty rich and rare.” Similarly, the Czech Republic’s national anthem’s title translates literally as “Where Is My Home?” The song’s simple, meditative music and lyrics convey the loveliness of the country’s landscape of pine trees, mountain crags, and flowing streams. A symbol of national reconciliationOther countries’ national anthems focus on their diversity and hard-won unity. South Africa’s national anthem, “Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika” is based on a 19th century hymn originally written in Xhosa that later became the anthem of the African National Congress. In the early 1990s, during the dismantling of apartheid, the country declared two national anthems: “Nkosi” and the Afrikaans apartheid-era anthem “Die Stern van Suid-Afrika” (“The Call of South Africa.”)

When the country won the 1995 Rugby World Cup, both songs were sung together. Today, South Africa's national anthem combines shorter versions of both songs into a single national hymn, with lyrics in five languages: Xhosa, Zulu, Sesotho, Afrikaans, and English. When students of any age are learning about music, they will find their studies enriched by learning about the history of different musical forms. The following survey of medieval Western music can serve as one doorway into this topic for young musicians, as well as for adult learners interested in the musical history of Europe. Defining an era beyond the stereotypesThe stereotypical view of anything “medieval” conjures up images of dank, fusty monasteries, brutal warfare, and stagnation in the arts and sciences. However, this is far from the truth. The Middle Ages in Western Europe were years of great creativity in the arts, sciences, and exploration. Authorities differ on which time span precisely defines the Middle Ages. The most generous reckoning begins the period at the fall of the Roman Empire in the late fifth century and ends it in the late 15th century AD. A world centered on prayerThe medieval period was characterized by the central place of liturgical music as both high art and a daily companion for the nobility and common people alike. The practice of singing psalms and setting prayer to music dates back much earlier than the Middle Ages, into the beginnings of human history. While much of this ancient religious music was performed a cappella, instruments often lent their voices to the mix, enhancing the sound. The medieval Christian church took many of its cues from ancient Jewish sacred music, in forbidding the participation of women’s voices after the late sixth century AD and limiting or curtailing instrumentation. In the church, mass was the chief occasion for the performance of this music, sung by priest, congregation, and choir. The choir typically filled an “answering” function, responding to the themes of the main part sung by the priest. The human voice as instrumentThe long tradition of prayer through song reached a pinnacle in the development of Gregorian chant, a variety of plainchant, during the ninth century AD. Gregorian chant is still often used today in Catholic ritual. This style of plainchant puts the religious text at the heart of the composition. The human voice is the only instrument used. The music of Gregorian chant is described as monophonic—it consists of one melody, sung in unison. The chant serves to frame the words of the prayers, rather than to overpower them. The majority of Gregorian chants originate in the Latin Vulgate, the version of the Bible in widespread use in medieval Europe. Although most Catholic congregations today celebrate mass in the community's vernacular language, traditional Gregorian chant holds an honored place, both esthetically and liturgically, in modern Catholic culture. Its popularity with both religious and secular audiences is attested by the many recordings now available. Hildegard von Bingen – a composer of mystic devotionHildegard von Bingen, later Saint Hildegard, was born in Germany at the close of the 11th century and died near the end of the 12th. This abbess, mystic, and prophetic visionary is considered one of the first and most talented female composers. Her monophonic works are characterized by soaring lyricism and a deeply felt spirituality. St. Hildegard set dozens of her own poems to music, assembling them into a collection entitled Symphonia armonie celestium revelationum. She was also a scholar who wrote widely on science and medicine and traveled as an itinerant preacher. Numerous musical ensembles have produced recordings of St. Hildegard’s surviving compositions in recent years, and contemporary audiences continue to find them musically and spiritually rewarding. Contemporary collections of her music have titles that reflect her mysticism: Canticle of Ecstasy, Music for Paradise, and A Feather on the Breath of God are only a few examples. Moniot d’Arras – exemplar of the trouvère estheticOne enduring tradition that flourished particularly in the later Middle Ages was that of the secular romantic balladeers and traveling entertainers known as troubadours and trouvères. Lutes, citterns, and other stringed instruments frequently accompanied these musicians' compositions, although their vocals often stood alone. The city of Arras, France, in northern France was noted as a center of the delicate and refined trouvère style. The trouvères’ style evolved roughly in tandem with that of the troubadours, although the trouvères typically composed lyrics in their northern French dialect, and the troubadours drew from the vernacular native to southern France, the langue d’Oc. One monk, Moniot d’Arras, earned widespread recognition as a composer in the early 13th century. While much of his output was focused on liturgy, many other pieces extol the culture of chivalry and courtly love between a nobleman and his lady. These were often the main subjects of troubadour and trouvère compositions. The sacred and the secularThe traditions of the troubadours and trouvères were part of the larger growth of non-sacred medieval music from about the 13th century onward. The ballade, the rondeau, and the virelai were the three leading types of secular compositions in France at this time. Guillaume de Machaut – lyricist supremeGuillaume de Machaut, considered today one of the towering figures of medieval European music, was born at the beginning of the 14th century and is thought to have lived well into his 70s. He wrote in both French and Latin.

Machaut composed one of the first polyphonic treatments of the mass, a development moving away from the monophonic plainchants. Polyphonic music features two or more independent melodies. Machaut's dozens of motets demonstrate the full flowering of this type of music. In 1337, Machaut became the canon of the cathedral at Reims. He wrote poems and musical compositions, with experts today viewing him as a master lyricist and versifier working in the then-current Ars Nova (polyphonic) style. Machaut also used and reworked the courtly love theme, creating beautifully constructed poems that blend technical virtuosity with lyricism. A large number of researchers believe that, for people of any age, listening to music while performing tasks at home, work, and school can have a beneficial effect on learning, productivity, and satisfaction. Here are a few facts about this effect: 1. Music improves productivity when working on repetitive tasks. One team at the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom found that playing background music while engaging in repetitive tasks—think spreadsheets, counting objects, and reading email—not only makes time go by more pleasantly, it serves to boost productivity. The authors of the study note that this held true for their test subjects even when they were in the midst of a considerable amount of ambient industrial noise. 2. Music is most effective when it is considered pleasant or neutral by the listener.A University of Miami music therapy professor discovered that when people hear music that they personally find enjoyable, they tend to start feeling better. Her test subjects—people who worked in information technology—reported finishing their assignments more quickly when listening to music they liked. Additionally, she discovered that the elevation in mood her subjects experienced propelled them on to come up with better ideas and insights related to their tasks. She concluded that personal choice regarding musical selections is extremely important to the effectiveness of that music in heightening mood and productivity. She went on to observe that over-stressed individuals tend to come to over-hasty conclusions about work tasks. On the other hand, individuals who were able to select their own music could see multiple possible solutions to a problem. Some investigators have discovered, however, that music we neither strongly like, nor strongly dislike, may be best for workplace productivity. A group of Taiwanese researchers at Fu Jen Catholic University found that extreme reactions—positive and negative—to music made it more difficult to maintain concentration. 3. Music triggers the release of dopamine in the brain.Biology tells us that the act of listening to music we enjoy releases hormones called dopamine into the brain’s reward center. This is the same reaction we experience when we look at a beautiful scene, drink in the scent of a rose, or eat a delicious meal. One physician at the Mayo Clinic who has studied the way people at work gain focus from listening to music notes that it takes less than an hour a day to achieve the mood-lifting and mind-opening benefits. 4. Music is most effective at increasing productivity when it is instrumental. One point seems to be consistent across a variety of research studies: the best music for concentration and productivity is wordless. Words that we can understand tend to distract the brain, since they pull us in the direction of trying to make sense of them. One study found that almost half of office employees in the test group were distracted by human speech. Trying to tune out the background noise of others’ voices won’t work if the music has lyrics. It will merely cause the brain to shift its focus. 5. The tempo of Baroque music may facilitate concentration and learning.The tempo of a piece of music has a strong impact on how well it facilitates concentration. Numerous studies have shown that music from the Baroque period in particular—think Bach, Vivaldi, Georg Telemann, Henry Purcell, and Jean-Philippe Rameau—aids learning and concentration, which contributes to longer-term retention of new information. In fact, authors Sheila Ostrander and Lynn Schroeder wrote the book Superlearning 2000, an update to their earlier title Superlearning, to further outline exactly how to use the steady, even beats of Baroque music to learn foreign languages, new vocabulary, and a host of other facts, figures, and real-world skills. Fans of the Super-Learning books say that the techniques and helpful resources the authors offer have helped them speed up their learning, recall much more of what they have read, and fully engage both hemispheres of their brains. Ostrander and Schroeder, who began putting the book together in the 1970s, drew on then-revolutionary research by top psychologists and neurologists. These scientists had discovered that listening to Baroque music in particular was capable of increasing the powers of a person’s concentration and memory. They posited that this was the result of the regular mathematical formulas that lie at the heart of the Baroque tempo. 6. Baroque music may facilitate the production of alpha waves in the brain.The 50- to 80-beat-per-minute tempo of Baroque, researchers have learned, is comparable to an adult’s resting heart rate. This makes it ideal for stimulating the production of alpha waves in the brain. These alpha waves are known for inducing a mood of deep but focused relaxation.

When human beings are in an alpha state—with their brain waves’ frequency measuring from 9 to 14 hertz, or cycles per second—they are far from being passive or inattentive. A person in an alpha state is calm but alert, and is extremely receptive to taking in and processing new information. Most of our daily lives are spent in the active beta state, with brain waves of between 15 and 40 cycles per second. This means the alpha state represents a significant reduction in our normal rhythms, giving us more time and space to notice things we may not have noticed before. Most experts date the Baroque period in classical music from about 1600 to 1750, putting it between the polyphony of the Renaissance and the era of Classicism (the period after the mid-18th century distinguished by the works of composers such as Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, and Schubert). Compositions from the Baroque period are typically marked by their grandiosity and drama as well as the numerous ways in which composers used the technique of counterpoint to express musical themes and ideas. Developments in the music of this period parallel those in the other arts—for example, massive and ornate buildings such as St. Paul’s Cathedral in London and the Caserta Royal Palace in Rome. Venetian Baroque-era churches, built with two opposing galleries, were ideal for the performances of two ensembles of musicians playing at the same time. A complex formThe concept of two voices or groupings in contrast with one another is a central idea in Baroque composition. Concertos (known in Italian as concerti grossi) featured a solo instrument or voice playing or singing along with a full orchestra. They were a favorite among Baroque composers. Baroque music tends to emphasize a bass line set against a melody. A cello, for example, might deliver the bass, while a vocalist sings a melody. The technique of counterpoint is central to the development and performance of Baroque music. Simply put, counterpoint is the art of combination. A composer working with counterpoint will juxtapose two or more separate melodic lines in a single composition. In counterpoint, individual melodic lines are known as “parts” or “voices.” Each part or voice has a distinct melody. The term “counterpoint” is sometimes incorrectly conflated with polyphony. Polyphony refers to the presence of at least two individual melodic lines in a composition. Although counterpoint evolved out of polyphonic music, counterpoint is a much more complicated technique. True counterpoint involves a complex handling of the several melodic lines of a composition to fashion an acoustically and emotionally meaningful and harmonious whole. The organ and the harpsichord are perhaps the instruments audiences most acquaint with Baroque music. During the Baroque period, these instruments offered two keyboards, allowing the musician to transfer from one to the other to create the rich blending of the contrasting sounds. A centuries-old technique that continuesComposers of the Classical period were usually steeped in the techniques of Baroque composition from their early years. Some, like Mozart and Beethoven, would go on to employ counterpoint extensively in their own later works, written well into the Classical era. Counterpoint continues to find favor today among musicians, composers, and even mathematicians, who have devoted much effort to explaining its symmetry and intricacy in terms of numerical relationships. The supreme artistry of BachNumerous critics and teachers have found the Brandenburg Concertos of Johann Sebastian Bach to represent a pinnacle of the development of the concerto grosso form, and of the Baroque style itself. Bach created these works over the span of the second decade of the 18th century, one of the happiest periods of his life. The six compositions masterfully weave together the component threads played by a smaller orchestra and by several solo groups. Music scholars point out that the scale of the Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 features so many soloists that it is more of a symphony than a concerto, in fact. Bach brought in oboes, horns, a bassoon, and a solo violin. And the third of these concertos features performances from no fewer than three cellos, three violas, and three violins. Unique among these concerti, Brandenburg Concerto No. 6 features not even a single violin; instead, it focuses on lower-voiced string instruments. Three centuries after their composition, the rich-toned, lilting Brandenburg Concertos remain among the most popular and beloved works in the classical repertoire. The art of fugueBach was a master of the fugue, and many musicologists revere his late work The Art of Fugue as one of his most significant creations. A fugue is a piece of music—or a part of a larger composition—that offers finely tuned and mathematically pleasing use of a central theme (the "subject") and numerous restatements and reconfigurations of that theme. In a fugue, the subject is taken up by other parts that are successively woven together. A fugue begins with an exposition, introducing the listener to the central subject. The subject then plays out in different parts, becoming transposed into various keys that serve as “answers” to the essential statement of the subject. A fugue can unfold over as many statements, restatements, and key changes as the composer would like, and can be as short or as long as desired, as well. Baroque composers worth knowingGramophone magazine, one of the world’s premier authorities in classical music criticism, recently put out its 2019 edition of the Top 10 Baroque composers.

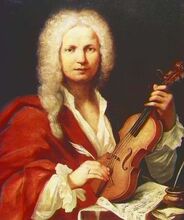

Bach heads the list, with the Gramophone team noting that he continues to enjoy a status in music equivalent to that of Shakespeare in literature or da Vinci in the visual arts. The publication particularly recommends Bach’s St. Matthew Passion as a supreme example of his musicianship and of the Baroque style. Next comes Antonio Vivaldi, whose lavish, ornate compositions echo the culture of his native Venice at the time. Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons is perhaps the best known of his works today. This lilting, exuberant hymn to the beauty of earth’s changing seasons is known for its exquisite craftsmanship. George Frideric Handel’s lively, upbeat Baroque compositions are other essentials for anyone becoming familiar with the era. His towering oratorio Messiah remains a not-to-be-missed composition for both music lovers and those devoted to the Christian faith. The experts at Gramophone additionally nominate English composer Henry Purcell, composer of Dido and Aeneas and other operas, to this select group. Claudio Monteverdi, remembered as a bridge between Renaissance polyphony and the early Baroque style, also made the list, as did Domenico Scarlatti, Jean-Philippe Rameau, Georg Philipp Telemann, Arcangelo Corelli, and Heinrich Schutz.  Vivaldi | Image by Wikipedia Vivaldi | Image by Wikipedia Antonio Vivaldi, born in Venice in 1678, achieved fame during his lifetime as one of Europe’s greatest composers. His works have continued in popularity over the centuries—his “Four Seasons” and other richly textured concerti, as well as his operas, are still beloved by listeners all over the world. Vivaldi’s influence on the development of Baroque music, particularly on the emerging form of the concerto, cannot be overstated. Even scholars, however, often overlook how he opened doors for the participation of women in music. Here are a few facts about Vivaldi’s work with an extraordinary group of Venetian female musicians, and how they themselves achieved renown for their gifts in an age when few women and girls had such an opportunity. “The Red Priest” and the orphanageVivaldi worked with the church and orphanage of the Ospedale della Pietà in Venice sporadically from 1703 to 1740. An ordained priest nicknamed “Il Prete Rosso” (“The Red Priest”), most likely due to his vivid red hair, Vivaldi soon ceased to administer the sacraments and concentrated on his work as a composer and teacher. At the Ospedale, he served as a violin master and, later, a concert master. He also composed large numbers of works to be performed by one of the world’s most accomplished—and largely unknown—musical groups: a chorus and orchestra made up entirely of orphaned girls and young women. The long history of the orphanage The Ospedale was a creation of the Middle Ages. Founded by a 14th-century Franciscan priest as a charitable home for orphans, it took in both boys and girls who had lost their families to famine, plague, and other horrors that were common in the Europe of that time. It was attached to the Church of Santa Maria della Pietà, which also served as a public hospital. Throughout the Middle Ages and early modern period, such institutions—a combination hospital, orphanage, and musical conservatory—flourished in Venice. The Pietà was one of four major ospedali that made the city a must-visit musical destination until the fall of the Venetian Republic at the close of the 18th century. Marketing a music schoolThe Ospedale needed a continuous supply of generous patrons in order to feed, house, and clothe the increasing number of children within its walls. Its most creative—and best remembered—marketing effort involved establishing a girls’ choir, composed of its orphaned singers and musicians. The school would test each child at around age 9, to see if she had the needed flair for music. If a girl showed promise, the school made sure that she would have access to the finest musical education possible. (Researchers believe that many of the girls were not, in fact, orphans at all but the illegitimate children of noblemen, thus providing an additional explanation for the lavish expenditure of funds on a fine musical education.) Giving young women performers a voiceBeginning in the 1600s, the Ospedale’s girls’ choir performed in religious pageants to which the population of Venice was invited. By the following century, the fame of this orchestra was such that visitors from all over Europe traveled to Venice to hear, incidentally providing significant new revenue streams for the church and orphanage. Some of the young women performers became legendary, earning nicknames based on their talents. There was “Maria of the Angel’s Voice,” for example, and “Laura of the Violin.” But of the hundreds of girls who lived at the Ospedale, only a few dozen at a time had the talent necessary to become members of the orchestra and chorus. Vivaldi’s compositions for the schoolVivaldi became the most famous of all the renowned instructors of the Ospedale’s girls’ orchestra and chorus. He composed numerous cantatas, concertos, and sacred works specifically for his pupils to perform. One stellar example: He created “Gloria in D Major,” one of the finest compositions in the entire repertoire of sacred music, for the group. The girls sang this piece while situated high up in the top-most galleries of the church, where they would be concealed from the curious stares of tourists and the rough-and-tumble public. The fact that they were afforded an additional layer of protection by a latticed grille only served to enhance the atmosphere of lyrical majesty and mystery of the Gloria in performance. Vivaldi built the Gloria’s dozen small movements into a joyous praise song for God and God’s creation, with the music depicting moods from deep melancholy to bursts of happiness. A deeply moving novelIn 2014 American author Kimberly Cross Teter published a young adult novel, Isabella’s Libretto, a work of historical fiction based on the girls’ orchestra at the Ospedale. Isabella, the novel’s protagonist, is an abandoned infant taken in by the orphanage. She grows to be a gifted young cellist with dreams of one day performing a work that she hoped Vivaldi would create especially for her. But Isabella is also a free spirit and an annoyance to the Ospedale’s head nun, who sets out to tame her by requiring her to give cello lessons to a new pupil whose burned face testifies to her escape from the fire that killed her family. Isabella finds the grace within herself to rise to this challenge, even as the passing years school her in the bittersweet changes that adulthood brings. Her favorite teacher marries and leaves the orphanage, reminding Isabella that any girl who leaves is bound by the Pieta’s rules from ever performing music in public again. And Isabella herself must weigh her love for her art with her growing preoccupation with thoughts of a young man who seems to want to pursue her. Her struggles with her decision about which future she wants for herself make for compelling reading and will draw in empathetic readers. A resplendent picture bookStephen Costanza’s 2012 jewel-toned picture book Vivaldi and the Invisible Orchestra mines the same fascinating ground to tell the story of the Ospedale for younger readers. In this treatment, orphan girl Candida becomes a transcriber of Vivaldi’s emerging works, creating sheet music for the use of the performers in the “Invisible Orchestra”—so called because the female players performed from places of concealment. Candida’s value goes unappreciated, until the day a poem she composed finds its way into the sheet music, and her own creative gifts receive their due. In the author’s imagination, Candida’s sonnets provide Vivaldi with the inspiration he needs to produce his “Four Seasons,” perhaps his most famous and beloved work. The Ospedale todayThe Church of Santa Maria della Pietà still bears a nickname signifying it as “Vivaldi’s Church,” even though construction on its present building on the Riva degli Schiavoni was not finished until decades after his death. Today, the church stands adjacent to the Metropole Hotel, which was built up around a portion of the older Ospedale that had housed the music room.

The present church, constructed in the mid-18th century, recently underwent renovation after having fallen into disuse and disrepair and has reopened for concerts. Today, the church’s social welfare outreach program is still in operation, serving its community with early education programs for young children and parents in crisis. Additionally, a museum exhibiting some of the items associated with the centuries-old Ospedale is situated nearby. Teaching the basics of music doesn’t always have to take place in school. While formal music education programs are vital for giving children an appreciation of music as one of the quintessential human activities—and are certainly needed when children hope to pursue a musical career—parents and families can provide numerous informal opportunities to develop their children’s musical gifts. Music has an innate and immediate appeal to almost all children, so get creative and make it one of the focal points in your family life. The following suggestions, advocated by a variety of music teachers and family educators, can help point you in the right direction: Turn “trash” into treasure. Use ordinary items found around your home, office, or yard to produce interesting and captivating sounds. For example, you can start an entire percussion section with a few kitchen and garden tools: Pots and pans, lids, watering cans, metal or wooden spoons, empty jugs, unbreakable bowls, water glasses, and other items can produce a wide variety of tones. Try banging the sturdier items together, or beat them with spoons or ladles to make an impromptu drum set. Fill a series of glasses with different levels of water and gently strike them with a spoon. This latter activity is a wonderful chance to create your own STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts, and math) lesson, as you and your child see firsthand how the amount of water in a glass affects the speed at which sound waves travel and therefore the pitch of the resulting sound. Other items that can produce a variety of sounds for your child’s enjoyment include that bubble wrap you were about to throw away, pens and pencils, or even crumpled-up newspaper or wrapping paper. Get crafty.Making his or her own musical instruments together with adults can add to the fun of a child’s musical education. In addition, reusing items that you would have thrown away can help your family gain a greater appreciation of the need for recycling and purposeful spending. Numerous websites, put together by parents and teachers, offer lively selections of ideas and directions for making a rich array of simple instruments. An old box that may once have held tissue paper can be fitted with rubber bands to fashion a simple guitar. Plastic Easter eggs can be decorated and filled with dry rice, beans, or peas to become wonderful shaker instruments. A paper plate with jingle bells attached to it with string becomes a tambourine. And balloon skins stretched over the tops of a series of tin cans can become an exceptional set of drums. After you create your own instruments, practice them together. See how many sounds you can coax them to produce, and even try writing and performing a musical composition using only the instruments you have made. Experiment together while emphasizing to your child that improvisation and exploration are more important than “perfection.” Connect with real musical instruments.If you can buy or borrow real musical instruments, bring them into your home whenever possible. Young children are likely to be especially tactile, so let them experience what a drum set, a clarinet, or a flute feels like in their hands. A visit to a local museum that has a music exhibit, or to a music store or university music department, can also provide this experience. Investigate whether your community offers musical instrument lending libraries, which are designed to provide access to music education for all people, regardless of income. Such libraries are available in some locations in the United States, but residents of Canada are especially fortunate. Toronto, for example, recently initiated a musical instrument lending program through its public library system. Library patrons can check out violins, guitars, drums, and other instruments, free of charge. Listen together.Bring live and recorded music from as many cultures and time periods as possible into your home. Practice your listening skills, and see if you and your child can recognize the sounds of the different instruments in a composition. Encourage your child to catch the beat by clapping, tapping a foot, or creating a dance in time with the music. Hit the books.Bring home a variety of music-themed books, including picture storybook classics like Zin! Zin! Zin! A Violin, written by Lloyd Moss and illustrated by Marjorie Priceman; or The Philharmonic Gets Dressed by Karla Kuskin, with pictures by Marc Simont. Older children will also find plenty of music-themed fiction in titles such as Bud, Not Buddy by Christopher Paul Curtis and The Trumpet of the Swan by E. B. White. Your local bookstore or public library will likely offer all of these, and many others, as well as informational books about music and biographies of great musicians. Unite music and art.You can also look for coloring books that feature images of musical instruments or music performances. Additionally, a simple internet search using the keywords “musical instruments” and “coloring pages” will yield many free images to download and print for your child to decorate. Creating visual representations of musical instruments and concepts will provide a multi-sensory experience that can deepen your child’s connection to the related art of music.

Whether tone poems are enjoyed in a concert hall or played in a simplified arrangement in school or at home, they offer young music students a rich variety of musical experiences. A tone poem is a musical composition designed for a full orchestra. It is designed to evoke, through the choice of instrumentation, tempo, and arrangement, concrete images and storylines in the minds and hearts of listeners. The titles of many tone poems further help the listener in that they acknowledge a composition’s roots in a famous legend, poem, picture, place, or historical event. A tone poem can conjure up visions of majestic mountains, forests, and waterways; knights on horseback gliding over desert sands; the appearance of magical beings, or the tender feelings between two lovers. And a favorite tone poem can make audiences feel transported, mentally and emotionally, to long-past heroic ages, or into the pages of beloved works of literature. Hungarian composer Franz Liszt is often credited with inventing the form of the tone poem, also known as the symphonic poem, in the mid-19th century. In this era of romanticism, revolution, and rising national consciousness, the form flourished. By the early 20th century, composers such as Igor Stravinsky were still writing richly orchestrated tone poems. However, the form began to shift toward using this type of colorful music as a background for dance performances, rather than as single-unit orchestral pieces. Here are brief summaries of what makes only a few of the best-known tone poems memorable: 1. The MoldauCzech composer Bedřich Smetana completed “The Moldau” after only 19 days of work in 1874. Since then, its central melody has become an iconic national symbol. The piece is one part of a six-section suite titled My Country, in which the deeply patriotic composer depicted the natural beauty and the rich cycle of history and myth of his native land. “Moldau” is the German name for the Vltava River, which flows from high forested mountains through the country lowlands and straight through the center of Prague. Smetana’s piece is by turns mystical, forceful, lively, and majestic, as it conjures up, first, the river’s quiet patter, then its sweep through a folksong-filled plain, to its destination near the capital, the royal seat of the Bohemian kings. 2. ScheherazadeRussian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov debuted his orchestral suite Scheherazade in 1888, offering audiences a collection of musical trips to the stories of the Arabian Nights. The deep, bold opening notes paint a powerful picture of Sultan Shahryar, and the sinuous lilt of the violin portrays his wife, the storyteller Scheherazade, with the later musical themes unfolding the stories she tells like the unrolling of a magic carpet. The four movements of the suite tell the story of Sinbad and his ship on the ocean; the “Tale of the Kalendar Prince,” bringing out the full capacity of the woodwinds to evoke an air of mystery; the tender and richly soulful romance of the story of a young prince and princess; and a finale that brings in themes from each of the previous sections, culminating in vivid images of a festival and the destruction of a ship on a wild, tempestuous sea. 3. FinlandiaIn 1899, Finnish composer Jean Sibelius composed and premiered his now world-famous tone poem “Finlandia” as part of a larger suite. Like Smetana, Sibelius was a patriot who used his music to challenge the rule of an empire over his small country. “Finlandia” was, in fact, originally written to be performed at an event protesting the Russian tsar’s censorship of the Finnish press. The work begins with the boom of timpani and brass to establish a somber and foreboding setting. As woodwinds and strings enter the musical conversation, they help to weave the type of stately atmosphere found in a king’s great hall. After a burst of forceful sound bringing in the sense of the whirlwind of struggle animating the Finnish people, the mood lifts. The piece concludes on drawn-out notes evoking a deep sense of serenity and majesty, as if listeners were looking down on sweeping vistas of dark-green Finnish forests. Soon after its composition, the central theme of “Finlandia” became popular worldwide, with many American communities using the melody for songs honoring cities, schools, and other organizations. 4. Fantasia Walt Disney’s 1940 full-length orchestral cartoon movie masterpiece Fantasia is a contemporary tone poem in itself. The film incorporates Disney’s retellings and re-imaginings of the stories behind several of the best-known symphonic works, including French composer Paul Dukas’ The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. In Disney’s version, Mickey Mouse is the hapless student of magic pursued by a pack of enchanted brooms.

Dukas’ original soundtrack debuted in 1897. He based it on a folkloric tale by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, one of the towering figures in the European literature of the Enlightenment. Dukas’ composition closely follows the sequence and spirit of Goethe’s piece by offering an opening that paints a picture of quiet, but magic-filled domesticity in the sorcerer’s workshop. But then the apprentice enters, represented by a leitmotif uniting oboe, flute, clarinet, and harp. A burst of timpani perhaps signals a stroke of enchantment. Then, through the composer’s use of a triple-time march, the sorcerer’s army of brooms comes lumbering, and then sprinting, to vivid life, carrying one bucket of water after another. Dukas masterfully uses strings to conjure up the flooding cascade of water that ensues before the sorcerer, accompanied by the gloomy moans of the bassoon, returns to chase away all the mischief. A movie musical night can be one of the most enjoyable ways for families who love music to spend time together. Particularly when a child in the house takes voice or movement lessons, or plays an instrument, musicals can open up new doors for musical understanding and creativity. Whether you rent, buy, or stream them, these old-fashioned classic musicals offer great lyrics and danceable tunes, as well as engaging storylines that are suitable for all ages. 1. The Sound of MusicRichard Rodgers’ and Oscar Hammerstein II’s The Sound of Music (1965), starring Julie Andrews and Christopher Plummer, will likely top the list of favorite movie musicals for many families. One of the most recognizable and beloved of the great movie musicals, it tells the story of Maria, a young novitiate in a convent who starts work as a governess for a widower and his large family, only to fall in love. Set in Austria at the time of the Nazi invasion that led into World War II, the plot offers a clear contrast between good and evil as the von Trapps struggle to remain true to their values and stage a perilous escape. The musical is based on the real-life experiences of Maria von Trapp, as told in her 1949 book The Story of the Trapp Family Singers. The many well-known songs from the musical include “Do-Re-Mi,” (“Do, a deer, a female deer…”). In addition to being one of the liveliest and easiest musical numbers for a young child to learn, the song is a great way to teach solfege, the art of training the ear to distinguish musical tones. Other wonderful pieces on the soundtrack include the poignant coming-of-age love song “Sixteen Going on Seventeen,” the raucously funny “The Lonely Goatherd,” and the poignant “Edelweiss,” a folk song that the von Trapps use to express their love of their homeland and their sorrow at leaving it. 2. The Wizard of Oz The Wizard of Oz (1939), based on the series of children’s novels by L. Frank Baum, is another widely beloved family classic, with a score by Harold Arlen and lyrics by E. Y. “Yip” Harburg. Dorothy, who was whisked away from her home in Kansas by a tornado, finds herself in the magical Land of Oz. She makes friends with the Tin Woodsman, the Scarecrow, and the Cowardly Lion, and together they make their way down the Yellow Brick Road to find the wizard who can give each of them their heart’s desire; and in the case of Dorothy, a return to her home. The Wicked Witch of the West does her best to thwart them, sending an army of flying monkeys to attack in a harrowing scene. However, after Dorothy and her friends defeat her, they reach the Emerald City and unmask the great wizard as a bumbling, ordinary man, with goodness triumphing over both the wizard’s cowardly bombast and the witch’s evil. The now-iconic songs that Arlen and Harburg composed for the film include the sweeping ballad “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” which became not only the centerpiece of the movie, with its theme of love and longing, but a lifelong theme song for star Judy Garland. 3. Singin’ in the Rain Singin’ in the Rain (1952), starring the phenomenal dancer and singer Gene Kelly, alongside comic master Donald O’Connor and the multitalented Debbie Reynolds, offers a warm-hearted story, memorable protagonists, and plenty of exuberant songs that have captivated generations. As the late movie critic Roger Ebert wrote, there are few rivals for Singin’ in the Rain as a viewing and listening experience of pure fun. The musical is set in Hollywood in the late 1920s, when silent films were being outclassed by the new “talkies,” leaving numerous former stars literally speechless when their real voices couldn’t match their onscreen images. Kelly plays a matinee idol who dislikes his co-star and falls in love instead with the ingenue played by Reynolds. Arthur Freed’s lyrics and Nacio Herb Brown’s music enhance the charm of the book by Betty Comden and Adolph Green. The film also offers O’Connor’s bouncy, show-stopping rendition of “Make ‘Em Laugh,” a lively trio performance by the three leads in “Good Mornin’,” and the kinetic magic of Kelly in the title number, sloshing, dancing, and singing his way against the shadows of a dark and rainy street. 4. The Music Man The lively sound of “76 Trombones” is only one of the highlights in The Music Man (1962), created by Meredith Willson for the stage and later for the screen.

Robert Preston plays the title character, a traveling salesman—more aptly, a charming con man—named Harold Hill. In the sleepy days of 1912, right before the town’s Independence Day celebrations, Hill descends on River City to persuade residents that only he and the new marching band he is forming can—at the town’s expense—save them from modern corruption, such as a newly installed pool table. “Ya Got Trouble,” Preston sings in one memorable song in his portrayal of Hill, as he tries to scare and con the town. “Right here in River City....With a capital ‘T,’ and that rhymes with ‘P’ and that stands for pool!” Hill mesmerizes everyone in the town, with the sole exception being young “Marian the Librarian,” portrayed by Shirley Jones. As the holiday nears, the completely unmusical Hill is about to be discovered. But before he can take his ill-gotten receipts and flee the town, he realizes that he’s fallen in love with Marian. He also suddenly finds it in himself to actually do the thing he only pretended to be able to do—lead a band—and he and the town are saved. Any family hoping to introduce their children to the wonders of onscreen musical theater will find much to enjoy in these four classics and in the many more made during this same era of the great movie musicals. |

Photo used under Creative Commons from Marina K Caprara

RSS Feed

RSS Feed