|

For many young children, the percussion instruments are the most fun to play and learn. Striking, shaking, or clanging these instruments produces an immediate response that the child can hear or sometimes even see. This easily grasped one-to-one correspondence between the child’s actions and the instrument’s sound is a big part of the appeal. Playing a percussion instrument is also valuable because it helps people of all ages improve their physical coordination, dexterity, and motor skills. In addition, percussion instruments give music students the chance to let loose creatively in ways that few other instrument types can equal. Researchers have even learned that drumming and practicing other percussion instruments can reduce stress and even improve the immune system. For all these reasons and more, percussion instruments are justifiably popular with student musicians, professionals, and audiences around the world. The following is a closer look at a few members of this truly global family of musical instruments. This list focuses on some of the more seldom-discussed instruments in the percussion family, and thus omits the piano and the many types of acoustic and electronic drums that are popular in the U.S. The boom of the timpaniIn Sergei Prokofiev’s classic Peter and the Wolf, an imaginative musical romp through the instruments of the orchestra, the crash of the timpani announces the arrival of the hunters. Timpani, also known as kettledrums, entered the Western musical world during the Middle Ages, imported by returning Crusaders and Arabic warriors arriving in western and southern European ports. Timpani came to be used in connection with trumpets to herald the arrival of aristocratic cavalry troops onto a battlefield. Timpani consist of large, round, copper-bodied drums shaped like half of a sphere. Their drumheads consist of sheets of plastic or calfskin stretched tight across the opening. A player produces sound by striking the instruments with sticks or mallets made of wood or tipped in felt. Timpani can be tuned to produce a variety of pitches when their drumheads are loosened or tightened via an attached foot pedal. In a typical orchestra, a single musician will play four or more timpani in a range of sizes and pitches. Playing the timpani calls on all the performer’s skills of attention and sense of pitch, since a typical orchestral piece calls for multiple tuning changes. The xylophone’s flexible rangeThe xylophone’s early history lies in Asia, most scholars believe, before it spread to Africa and then to Europe. The instrument’s name derives from an ancient Greek word that refers to its wood-like tones. The common denominator among the many types of xylophones available today is that the typical xylophone consists of a set of keys, or bars, organized in octaves, like piano keys. Affixed beneath the keys are a series of resonators, or metallic tubes, which produce the sound. Xylophones can be simple toys for the youngest children or sophisticated, multi-octave orchestral instruments. The xylophone player strikes the keys with a mallet. Mallets are produced in varying degrees of softness or hardness; changing the pitch of the xylophone involves using a different type of mallet or changing the way one strikes the keys. The xylophone’s close relatives in the percussion family include the larger and more mellow-toned marimba, the smaller and jingly-voiced glockenspiel, and the vibraphone. The Jazz Age vibraphoneInvented in the 1920s, the vibraphone is distinguished by its metal keys and resonators and by the addition of little spinning discs, or fans, in its interior. These small discs are electrically powered and are arranged under the keys and over the resonators. A player uses felted or wool-tufted mallets to strike the keys. He or she tunes the vibraphone by means of a motor that turns a rod connected to the discs. The resulting sound is the type of shifting, sliding pitch that’s referred to as vibrato when produced by the human voice. The vibraphone has found extensive use in the popular jazz repertoire of artists such as Lionel Hampton. The instrument’s first appearance in an orchestra was in the 1937 Alban Berg opera Lulu. The cymbals – the orchestra’s alarm clockThe crashing of the cymbals in the orchestra makes everyone take notice. A set of these ultra-loud percussion instruments consists of a pair of large discs, ranging in size from 16 to 22 inches in diameter. These discs are typically fashioned of spun bronze. A player hits the cymbals together, or in the case of suspended cymbals, strikes them with a mallet. In general, larger cymbals produce lower sounds. The waterphone’s New Age appealThe waterphone is a newer innovation in percussion. Patented in the 1970s and based on a Tibetan water drum and other instruments, the waterphone consists of a bowl of water, a resonator, and a series of differently sized metal rods. A player uses a mallet, bow, or his or her own fingers to produce sound by striking the rods. The vibration causes the water to shift in the bowl, thus altering the shape of the resonance chamber and creating a whole range of gliding sounds and echoes. Musicologists have described the waterphone’s sound as mysterious and otherworldly, and the instrument is noticeable in many television and film soundtracks. The triangle’s thousand-year-old lilt The triangle is a simple steel bar bent into the shape of an equilateral triangle, with part of one corner left open. The player strikes the instrument with a simple steel rod.

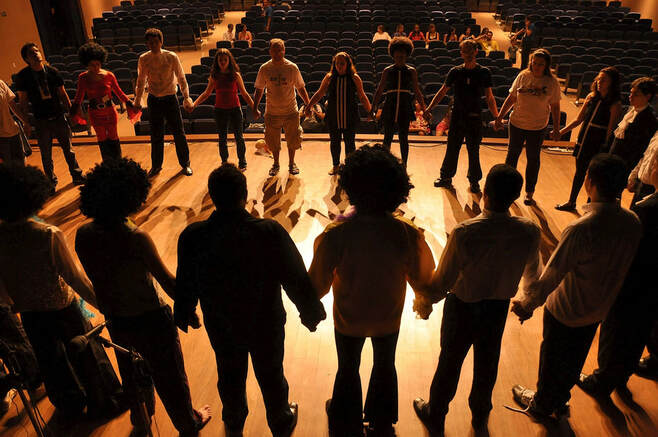

In use at least since the Middle Ages, the triangle often featured an attached set of jingly rings until the early 19th century. As European audiences of the 1700s demanded music in the Turkish style, Western musicians paired the triangle, the cymbals, and the bass drum into an ensemble with the aim of replicating the popular Turkish Janissary sound. The triangle’s piercing pitch is audible even over the sounds of a full orchestra. Accordingly, classical composers tend to use the triangle sparingly, often to add punctuation to a composition. At Music Training Center (MTC) in Philadelphia, children can take lessons in music and voice training. They can also participate in an a cappella vocal ensemble, Rock Band classes, or a number of high-quality musical theater productions. Over the years, Music Training Center has nurtured the talents of a number of promising young musicians and performers. The musical theater component is one of the organization’s signature programs. Kids in the upper elementary, middle school, and early high school grades can participate in its Main Stage musical production. Younger kids work on their own Junior Stage and Mini Stage productions. Popular musicals serve as an excellent way to engage kids with learning the basics of musical theater stagecraft. Experts in the performing arts have noted musical theater’s ability to develop a wide range of essential talents and skills in children who are considering making any branch of acting or performing a lifelong career. Further, musical theater training can lay the foundation for the kind of self-confidence, physical and mental stamina and agility, and personal presentation skills that will enhance a young person’s performance in any other type of career later on. There are many reasons to encourage your child to participate in musical theater. Here are four: 1. Musical theater programs are available throughout the countryThe MTC program is only one of many across the country that focus, either year-round or as a special summer experience, on the wealth of benefits that participation in a musical theater production can provide for children. The Performers Theatre Workshop in New Jersey, the Music Institute of Chicago, and San Francisco Children’s Musical Theater are only a few more examples of organizations that offer this kind of vibrant and engaging—and potentially life-changing—programming. 2. Musical theater helps teach movement, communication, and confidence.For example, kids who participate in musical theater training learn a whole set of movement skills. These skills can improve coordination, kinetic awareness, and overall fitness. In addition, training the voice to perform songs in a musical theater production tends to strengthen the vocal chords. They also benefit the performer’s overall voice presentation. This is a helpful tool for leaders and communicators in any field. Experts in teaching musical theater additionally point out that confidence is among the main takeaways from participation for many kids. Musical theater can take performers far beyond their familiar comfort zones. A student who primarily views herself as an actor might be asked to sing in a particular production. Another who thinks of himself only as a dancer might be called on to learn and speak lines of dialogue to convey an emotional experience. These activities might at first give young performers a case of nerves. Ultimately, however, this type of multifaceted training can open doors onto new ideas, build new skills, and create a sense of accomplishment in ways that stay meaningful over a lifetime. 3. Musical theater boosts self-esteem. One dissertation-related study, published in 2017 under the auspices of Concordia University-Portland, found that music and theater studies, individually, offer enormous potential. They can help middle school students develop their self-esteem and their scholastic achievement. The study goes even further by exploring the ways in which the combination of the two subjects in musical theater can lift up middle school students’ sense of self-worth and facilitate their achievement in a number of ways. In this particular study, about a dozen suburban private school students in Minnesota took part in staging a musical theater event. The researcher used direct observation, interviews, school records, and Likert scale surveys to gauge the degree to which the students engaged in a positive or negative way with the experience. The study concluded that if a student came into the production with already-high levels of self-esteem, he or she did not experience an additional boost of self-esteem from participation. On the other hand, if a student had a lower level of self-esteem before the production, he or she was more likely to develop more openness to being flexible and taking on novel tasks during the course of the production. These students also showed increased comfort with the process of change during the production. 4. Musical theater is fun!One remaining important aspect of performing in musical theater: it's fun. Kids of all ages enjoy meeting familiar or intriguing characters from movies, books, or TV shows translated onto the stage.

When they take on the personas of these characters themselves, they can find creative new ways to express themselves. They can also deepen their awareness of their own emotions and let their imaginations take them on new adventures. Can the study of music, or a program of music therapy, help children struggling with emotional or behavioral disorders? A growing number of experts say it can. Emotional disorders in children and adolescents can have a number of negative or potentially dangerous consequences. These can include a chronic lack of academic success, aggression against peers, isolation from others, substance abuse, running away from home, and even violence against oneself or others. Children with emotional and behavioral disorders may have extremely limited functioning in one or more areas. This can prevent them from engaging in a healthy way with their families, schools, or communities. A comprehensive plan of general psychological or psychiatric therapy is likely to be the lynchpin of any successful program to treat these conditions. However, such a plan can be enhanced considerably by the incorporation of music. Music can help in a variety of ways.Music therapy can improve a child’s self-image, and can help him or her develop much-needed self-esteem and a clearer and stronger personal identity. For any child or teen who has experienced abuse, this type of therapy has the potential to promote positive new attitudes about themselves and their worth. Recent research has demonstrated the capacity of music therapy to help in several specific ways in working with children with emotional disorders. These involve the regulation of the child’s own emotions, developing communication skills, and addressing challenges with social functioning. Music therapy has proven extremely useful in decreasing children’s levels of anxiety and developing their ability to be emotionally responsive. Young people who have difficulty controlling their impulsivity have also been helped by music therapy. In fact, a carefully structured and appropriately repetitive series of experiences that engage multiple senses, presented within a context of acceptance and support, can be of immense value in a variety of clinical settings. Some research has even suggested that the use of music can even produce a sense of relaxation that leads to improved performance on a range of assessment metrics. Music fosters positive social interactions. The use of music in therapy provides young people with a topic of conversation. This makes it an excellent starting point for establishing comfort within a social group and for fostering healthy self-expression. Music can help a child experiencing social challenges to gain greater awareness of the presence and feelings of others. It can also facilitate greater levels of cooperation with peers and adults. Children who participate in music therapy have also shown a decreased level of disruptive incidents as reported in psychological studies. Music’s value as a social harmonizer in the general classroom becomes especially important when working with children with emotional and behavioral dysfunction. This is because it can help establish a positive atmosphere and encourage the development of cooperative skills. Experts point out that, once such a foundation is laid, it can be used to build a child’s social skills out still farther. Music teaches new skills and builds confidence.At least one researcher in this field has reported that a series of carefully-structured experiences with music, supported by targeted and easily understood reinforcement, enabled children labeled “delinquent” to gain a positive self-concept. In one study, a 12-year-old with significant behavioral issues who learned to play the piano gained constructive new communication skills, made measurably fewer negative statements about themselves, and showed notable motivation to continue learning music. Music improves verbal and nonverbal communication skills.Songwriting, or communicating through the lyrics of a song, can offer a non-threatening means of communication. For many children with emotional difficulties, speaking through lyrics makes self-expression much easier. Music also has an appeal beyond the realm of the verbal. This makes it an ideal tool for connecting with young people who may be hard to reach, who may themselves be non-verbal, or who may feel threatened by engaging in direct, one-to-one conversation. One perhaps underappreciated benefit of music therapy as a non-verbal means of communication is that it is nonthreatening. When listening to music, a child may feel they have a safe space in which to engage with emotional issues that might otherwise feel too complex or unsettling to confront. A skilled music therapy practitioner can even tailor-make a program to assist a child in coping with overwhelming emotions such as grief, anger, or trauma. Experts point out that for many young people with serious emotional issues, music can become both an outlet for expression as well as a core therapeutic component. For many children in this population, it serves as an effective way for them to establish communication channels with therapists, parents, teachers, and peers. Music has significant short-term gains.In a study based in Northern Ireland, a cohort of some 250 school-age children and teens exhibiting a range of emotional and behavioral challenges were divided into two groups. One received treatment via music therapy. The other received the current standard of care. More than half the total cohort had exhibited significant levels of anxiety.

The young people who participated in the music therapy program explored improvisation and music creation through singing, movement, and playing musical instruments. The therapist worked with the youth for half an hour at a time, for 12 weeks total. Through these sessions, the therapist was able to contextualize the experience and provide a supportive atmosphere with the ultimate goal of improving communication and social skills. The study showed that, in the short term, the group that received music therapy showed decreased levels of depression and increased feelings of self-esteem. Communication skills appeared unchanged. Longer follow-up studies showed that the improvement in other areas eventually dropped off. The conclusion: at least on a short-term basis, music therapy may be helpful for young people with a range of behavioral and emotional challenges. Zoltán Kodály ranks among the foremost music educators of all time. He was born in what is now Hungary in 1882, and, well before his death in 1967, had earned an international reputation as a composer of highly original pieces, a scholar of folk music, and the originator of the method of music instruction that continues to bear his name. The Kodály Method has become widely known among music educators for its dynamic, interactive, and movement-oriented approach to instruction for children. It incorporates a set of proven techniques that foster the unfolding of a child’s natural gift for musicianship. The approach, which focuses on creativity and expressiveness, has demonstrated its relationship to the traditional ear-training method. During Kodály’s lifetime, his influence was felt throughout Europe and the world as an instructor who taught numerous teachers, and his method continues to be popular today. A young composer and teacher finds his vocation.In his youth, Kodály studied the piano, cello, and violin. When he was in his teens, his school orchestra performed several of his compositions. In 1900, he enrolled at the University of Sciences, located in Budapest, and became a student of contemporary languages and philosophy. He went on to study composition at Budapest University, but before graduating, he spent a year criss-crossing Hungary on a search for sources of traditional folk songs. He then centered his university thesis on the structural properties of Hungarian folk songs. Shortly after graduating in 1907, Kodály accepted a position in Budapest teaching the theory and composition of music at the Franz Liszt Academy of Music. He would remain on the school’s faculty for 34 years. Even after retiring, he returned to the school in 1945 to serve as a director. His dedication was driven by a desire to preserve his country’s musical culture, particularly in light of the unrest that characterized its political scene in his time. Before he entered into his duties at the Liszt Academy, Kodály met fellow Hungarian composer and folk music collector Béla Bartók. Together they published, over a span of 15 years, a folk song series based on their research. The series became the core of Hungary’s authoritative corpus of popular music. A 20th century master of styles.Kodály’s own style as a composer was anchored in the folk music that he loved and had a richly Romantic tone, while incorporating classical, modernist, and impressionistic techniques, as well. His best-known works include a concerto for orchestra, chamber pieces, a comic opera, groups of Hungarian dances, and the 1923 work Psalmus Hungaricus, which was created to honor the 50-year anniversary of the fusion of Buda and Pest into a single city. The piece brought him international fame and conferred upon him the mantle of musical spokesman for the culture of his country. As both a scholarly writer and musician, Kodály in his later years penned numerous books and articles on Hungarian folk songs. An evolving method.One story, perhaps apocryphal, has it that Kodály was so disappointed when he heard a group of schoolchildren perform a traditional song that he decided to improve the state of Hungarian music instruction himself. Kodály put nearly as much emphasis on developing his music education program as on his own creative works of composition. His interest in the issue of music teaching was intense, and he produced a variety of educational publications designed to expand the horizons of teachers. Kodály thought that music was among the vital subjects that should be required in all systems of primary instruction. He further stipulated that it be presented in a sequential framework, with one step logically leading to the next. He believed that students should enjoy learning music, that the human voice is the premier musical instrument, and that the most accessible teaching method incorporates folk songs in a child’s original language. Kodály himself was primarily the originator of his eponymous method, generating numerous ideas and principles that now form the basis of its core teachings, as used in classrooms today. However, it was left to the Hungarian teachers that he trained and inspired to fully develop it over time, often under his direct guidance. The Kodály Method serves as a comprehensive system of training musicians in the reading and writing of musical notation, as well as the acquisition of basic skills. In doing so, it draws upon proven techniques in the field of music instruction. It is also in itself a philosophy of musical development that emphasizes the experiences of each learner. The importance of the human voice. One of the basic principles of the method is singing, which Kodály himself viewed as the core of his system. The Kodály Method stresses that, first, a child should learn to love music for the sheer fact that it is a sound made by other human beings, and one that makes life richer and happier. Teachers of the method also emphasize the human voice as the one musical instrument accessible to most people around the world as a common means of expression. One reason why singing has such a central role in the method is the idea that the music one creates by oneself is better retained and provides a greater feeling of pride and personal accomplishment. The Kodály Method therefore places singing—and reading music—ahead of any sort of training on an instrument. Kodály also believed that singing was the best means of training the inner musical ear. The content of any classroom based on the Kodály Method will consist largely of folk songs from a child’s own heritage, as well as those of other cultures. Classic childhood rhymes and games will also be included, as will pieces of great music produced in any time and place. Continuing the work. Since 2005, the Liszt Academy has hosted the Kodály Institute, which provides advanced-level music education training for teachers, based on the Kodály Method. The institute works as the guiding force for the entire set of music instruction programs of the academy. In addition to its teacher-training programs, the institute offers the International Kodály Seminar every two years. Participation in the seminar is open to music teachers around the world and coincides with an international festival of music. The next seminar is scheduled to take place in July 2019. For more information, visit Kodaly.hu.

Folk songs in the classroom offer numerous ways to build a strong and engaging music curriculum. Recent surveys by the National Association for Music Education (NAfME) show that its members are in near-unanimity in favor of teaching American heritage folk songs as a major part of the music curriculum. Zoltán Kodály, an early 20th-century Hungarian musicologist and music educator, held folk songs in the highest esteem as musical teaching tools. Today, teachers around the world make use of folk songs either through lessons based on the Kodály method or informally, as a means of enhancing the music curriculum and the study of other subjects. At the heart of the Kodály method is instruction in singing, movement, and playing musical instruments, with folk songs as the core content. This helps children to learn the traditional songs of their own cultures, and develop an appreciation for the richness of other cultures as well. Read on for some more interesting ways to use folk music in the classroom and beyond. Simple examples to inform music lessonsFolk songs, with their simple, repetitive musical phrasing, can serve as excellent means for teaching the basics of musical notation, harmony, tempo, rhythm, pitch, and artistic expressiveness. A wealth of classroom usesFolk songs also afford an opportunity to enrich STEM- and STEAM-focused learning. They can be used in physics classes to illustrate the science of sound, in art programs in conjunction with an activity involving making musical instruments, or as examples of various points in American and world history. With their catchy, easy-to-remember lyrics and rhythms, folk songs have become key components of popular repertoires for school bands, choral groups, and dance troupes. A springboard for creativityBecause they’re highly adaptable, folk songs can accompany any number of games or playground activities. They encourage movement and the physical joy inherent in music. Children can enhance the experience themselves by creating their own dances and games to accompany the songs. They can write pastiches that employ similar themes, or update the songs’ historical themes in amusing ways. A way to strengthen memory and memorization skillsTheir easy-to-recall rhythms and refrains make folk songs excellent tools for training the memory, as well as helping with recall. For instance, in adults with dementia and other cognitive disorders, the simple, familiar lyrics and melodies of traditional folk songs can bring about pleasant and soothing associations with their childhood. Refining children’s ear for languageFolk songs can help children to expand their vocabulary through the use of rare and unusual words. Students may not immediately understand some of the dated language in a song, but once they learn the new words, they will have added to their store of language, as well as to their ability to express themselves and communicate within a new framework of ideas. A number of researchers have drawn a strong connection between learning folk songs and learning the finer points of English grammar and syntax. Thanks to the memorable patterns of rhyme, rhythm, and repetition found in folk songs, this learning technique can be especially useful and meaningful for English language learners. Additionally, folk songs can help listeners to mirror and model correct word pronunciation and accent, while repeated singing or listening to a folk song will continue to reinforce the grammar and articulation of that particular song. A web of historical connectionsThrough folk songs, students learn not only about their musical heritage, but about the historical events that have shaped this heritage—and their own lives. These songs connect children to generations of people—in their culture and in others—who have come before them, and whose lives made the world what it is today. On its website, NAfME lists a number of American folk song genres that have developed over time, each deserving a closer look from teachers and students. These include African-American spirituals, Shaker tunes, songs of the Civil War, and work songs sung by railroad workers, seamen, and cowboys. Each can provide an intimate insight into what the lives of a wide range of Americans were like. A few historical examples Teachers who devote time to teaching some of the history behind folk songs have found that it often piques their students’ interest in learning more about the historical topics addressed. Children often enjoy hearing about the origin of a song and its history as played, sung, and danced to by various peoples over time.

Some teachers find that folk songs are a good fit with material geared to meeting state core educational standards. For example, many states’ official state songs are folk songs comprising multiple historical references, and as such are culturally, musically, and historically a part of every American child’s history. For example, “Yankee Doodle,” sung during the American Revolution by British and Colonial soldiers alike, is the state song of Connecticut. The official state gospel song of Oklahoma is “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” attributed to the former slave Wallace Willis, who, upon seeing Oklahoma’s Red River, is said to have been reminded of the Jordan River and the Bible story of the prophet Elijah being lifted into heaven in a chariot. The song “Shenandoah,” also known as “‘Cross the Wide Missouri,” is said to have originated with the French adventurers and fur traders, called voyageurs, who traveled along the Missouri River in the early days of the European push westward in North America. The song references a voyageur who fell in love with a Native American woman. It later was widely adopted by American sailors. Its mysterious references and simple, haunting melody have kept it at the center of the American folk song corpus for generations. Recordings of songs like “Shenandoah” can additionally serve to acquaint children with great singers in the American popular canon, such as Paul Robeson. In the 1930s, Robeson recorded a number of versions of the “Shenandoah” tune. Pete Seeger, Arlo Guthrie, Bruce Springsteen, and Tom Waits have also recorded their own versions. Comparison of the various versions of the song could be particularly instructive for older students studying vocal interpretation. The study of an instrument is a long-term commitment. Students will need to feel comfortable with their choice and dedicated to getting the most out of their studies. With hard work, focus, and diligence, however, learning to play an instrument can be a way to enrich a child’s life well into adulthood. The following seven tips can help parents, educators, and children identify the instrument that will be the best and most enjoyable fit. 1. Consider the child's age and development.First, consider the child’s age. For particularly young children, consider the physical and developmental demands of each instrument. Children of this age may not have the physical strength, dexterity, or muscle fluency to manage certain instruments. 2. Consider the piano and the violin, particularly for younger children.  Expert teachers typically recommend the violin and the piano for children under 6 years of age. Both of these instruments serve as excellent building blocks for learning music theory and practice. They also assist with learning to play additional instruments. The Suzuki Violin Method is one of the teaching practices that focuses specifically on the qualities of the violin as a young beginner’s instrument. Learning violin is made easier for younger children because the instrument can be fashioned in very small sizes. This makes it simpler and more intuitive for a child this age to manage fluidly and naturally. The violin is also an excellent choice of instrument for teaching young music students to play in tune. Another advantage is that the act of bowing provides a kinetic manner through which students can learn the concept of musical phrasing. And, because the violin has no keys or frets, a young player can concentrate completely on the sounds he or she is creating. The piano offers its own plusses as a first instrument. A child learning to play the piano picks up foundational skills of musicianship by becoming proficient in harmony and melody at one and the same time. Piano students gain experiential knowledge that will help them to better understand music theory. 3. Consider the child’s physical abilities and limitations.An instrument’s design and its fit with a child’s physicality is also an important consideration. If a child’s hands are relatively small, for example, he or she may not have the finger span to become an accomplished pianist or a player of a larger stringed instrument. For woodwinds and brass instruments, make sure that the embouchure—the place where the child places his or her mouth to produce sound—is a good fit. Keep in mind that some students take time to learn the best way to address this. The oboe has a double read mouthpiece and the French horn has a slender tube mouthpiece. As a result, these instruments present particular challenges regarding their fit against a player’s mouth. For children who need orthodontic help, it can be better to select a stringed or percussion instrument. This is because blowing through any sort of embouchure may be uncomfortable or even painful. 4. Consider which instruments the child enjoys listening to.Sound is an important quality as well. A child should enjoy the sound her instrument makes. Otherwise, he or she may be reluctant to continue practicing and playing it. Experts point out that it is unrealistic to believe that, over time, a child will come to like the sound of an instrument he or she dislikes. Such a child may, instead, neglect lessons and resent practicing. This is particularly important for parents to remember, because band directors sometimes encourage children to take on specific, less-popular instruments simply because one is needed in the ensemble. 5. Consider the child's temperament.A child’s personality is another good indicator of the best instrument to select. For example, an outgoing child who enjoys being the center of attention will likely gravitate to an instrument that offers greater potential for front-of-the-band performance and solos. These instruments include the flute, saxophone, and trumpet. All are made to carry a central melodic line, rather than to play supporting roles. 6. Consider the social implications of the selected instrument.One factor sometimes swept aside by adults can have a big impact on children. This factor is the social image of an instrument, and what that says, by implication, to peers about a child’s own image and personality. Many children gravitate toward the instrument they perceive as having the most status among their peers. Unfortunately, that instrument may not be the best fit. Adults should encourage each child to take a fresh look at the instrument that actually seems best for him or her. 7. Consider your budget as well as any maintenance commitments.Practical issues of cost and maintenance will also be on most parents’ lists when choosing an instrument. Take some time to go over a realistic timetable of maintenance with a child’s music teacher. A piano, for example, is one of the most expensive instruments, and needs to be tuned twice annually by a professional.

Remember that many music vendors offer monthly payment programs. A trial rental may also be a good option until a child is certain that he or she really likes an instrument. Some schools will facilitate free long-term loans of instruments for their band members. It may also be worthwhile to explore options provided by nonprofit groups. For example, Hungry for Music supplies children in financial need with donated and carefully refurbished instruments. Children love music and picture books. This means that parents and educators are constantly on the look-out for new books to share that nourish a love for both music and reading. Today’s picture book writers and illustrators are producing work that is distinguished by rich literary and visual imagination. Among these treasures are a number of works that convey, in the sounds of their vocabularies and through the skill of their illustrations, what it feels like to make and enjoy music. Here are only a few of the best picture books published in 2018 whose storylines focus specifically on music. All of these titles will be found in most online and bricks-and-mortar bookstores as well as in many public libraries. 1. The Bunny BandThe Bunny Band was written by Bill Richardson, illustrated by Roxanna Bikadoroff, and published by Groundwood Books. It presents young readers and their families with a delightful adventure into the ways in which music can facilitate even the most unlikely friendships. Lavinia is a badger who cherishes her carefully tended vegetable garden. Suddenly, she realizes that an unknown someone has been eating her lettuce and taking her other produce. She sets out to catch the thief and discovers that it is a bunny. The angry badger threatens to put him into her stew pot, but the little rabbit begs her to spare him. In return, he promises her a mysterious reward. After Lavinia shows mercy on the repentant thief, she receives a surprise. The next evening, in the moonlight, her new friend returns, bringing with him lots of other bunnies, each one bringing a musical instrument. This lively bunny band pours delightful music into Lavinia’s garden with a host of banjos, ukuleles, trumpets, drums, and even a set of bagpipes. Much to the badger’s surprise, the music makes the garden grow! In thanks, Lavinia treats all the bunnies to a surprise: a feast made from the produce in her garden. The book’s rich and whimsical illustrations show the individual personalities of Lavinia and the entire bunny musical troupe. They are engaging for readers of all ages and convey in line and color the spirit of joyful music shared among friends. 2. Khalida and the Most Beautiful SongKhalida and the Most Beautiful Song, written and illustrated by Amanda Moeckel and published by Page Street Kids, is a symphony in pink and purple watercolors. Khalida is an overscheduled child. She wants nothing more than to capture the elusive song that whispered briefly to her one evening. But no matter how she tries, the time and place are never right. Her busy life comes between her and her ability to sit down at the piano to do the creative work she longs for. Even through adversity, Khalida persists in her quest for the essence of the song. Her perseverance is at last rewarded. The young girl’s love of music, and the beauty of the song she is finally able to catch, are made palpable through Moeckel’s flowing, elegant pictures. These serve as a visual counterpoint to the musical flow of the text. 3. New York MelodyWith its delicate tracery of laser-cut shadow images and sharp black-and-white shapes, New York Melody was written and illustrated by Helene Druvert and published by Thames & Hudson. It is a keepsake book to treasure. The simple story begins at Carnegie Hall. A single musical note on a page of sheet music gets free of its comrades and goes off on its own to explore the wonders of New York City. It drops in on a secret little jazz club, pays a visit to Broadway, and at last finds an island of peace as it joins in with a guitar player in Central Park. The guitar’s melody catches the ear of a passing cyclist, who carries the tune all over the city, causing passersby to pause in enchantment. Along its journey, the note works in tandem with numerous instruments, including a saxophone, a double bass, and a trumpet. The depiction of this last instrument, in glowing, vivid gold, presents a visual delight amidst the book’s otherwise monochromatic palette. Druvert’s book has a genuine ability to make the aural delights of music palpable through words and pictures. Additionally, it captivates readers with a tour through famous—and not-so-famous—New York landmarks. 4. The DamDavid Almond is best known for Skellig and other darker, edgier novels for older children. He worked with illustrator Levi Pinfold and publisher Candlewick Studio to create in The Dam a haunting tribute to the power of music to memorialize and recreate a lost world.

The book is based on the true story of the creation in Northumberland, in the 1970s, of the Kielder Water reservoir and dam. It resulted in the largest man-made lake in the United Kingdom. The region has historically been rife with legends and home-grown music produced by the people who lived on farmsteads all over the valley. In Almond’s re-imagining, a father and his young daughter return to the village after it has been abandoned. They know that the dam about to come into being will flood the land they love, burying the many abandoned stone houses under the waters. In Almond’s story, the father and daughter go from empty house to empty house, filling them for one last time with music from the girl’s fiddle. Pinfold’s muted, elegiac art provides the perfect accompaniment for this tale of loss, remembrance, and finding emotional resilience through the creation and performance of music. Historians point out that, by the time the real dam at Kielder Water was constructed, the buildings had all been razed. However, The Dam’s vividly etched tribute to things lost will ring true for readers of all ages. Not even a sprawling dam and the rushing in of mighty waters, the book tells us, can still the human longing for creating new worlds—and remembering old—through music. Experts point out that nothing encourages children to love reading more than when a parent sets the example. Children who see the adults in their lives taking time to read for pleasure are more likely to become enthusiastic readers themselves. So why not do the same thing for classical music? One way to start children off with a love of music is to model exactly what that looks like: Play musical games together, dance and sing as part of regular family activities, attend concerts, and enjoy recordings of great music together. But how can a parent demonstrate a love for classical music if he or she hasn’t had the opportunity to develop a taste for it? Fortunately, a number of popular books—all written for interested adult laypeople by experts in the field—are available. The following list represents a sampling of fascinating books that can inspire a love of serious music while providing an enjoyable, educational read. 1. Experience the wonderYear of Wonder: Classical Music to Enjoy Day by Day by Clemency Burton-Hill offers simple, one-page summaries—each tied to a specific day of the calendar year—of the delights to be found in 365 different pieces of music. The 2018 book, published by Harper, brings this expert musicologist and media personality’s extensive knowledge of the subject within easy reach of anyone who has time to read one page each day. The book offers a fun way to browse through Burton-Hill’s carefully curated selections as she provides fascinating snippets of information about each work, its composer, and its historical context. While it makes a delightful browsing book, Year of Wonder can also be used as a personal tutor through a year of discoveries in classical music. Readers can look for online or hard-copy recordings of each work, making for an enriching multimedia listening and learning experience. 2. Glimpse fascinating livesThe Indispensable Composers: A Personal Guide, written by Anthony Tommasini and published by Penguin Press, is another 2018 title that provides a wide-ranging journey through the history of great music and exactly how its creators made it. Tommasini serves as the New York Times’ head music critic, and his encyclopedic knowledge of his subject is on vivid display in this book. His assessment of each composer is easy-to-understand, free of jargon, and completely accessible, and is often accompanied by fascinating anecdotes and discussions of other cultural figures and of the author’s personal experiences in the world of music. Even those who are unfamiliar with the ways in which, for example, Beethoven’s concertos or Arnold Schoenberg’s twelve-tone technique revolutionized music will be able to grasp the significance of these and other big moments in the history of the classical music genre. 3. Catch the enthusiasmA Mad Love: An Introduction to Opera by Vivien Schweitzer, published in 2018 by Basic Books, brings the world of opera down to earth for even the most skeptical contemporary reader. Schweitzer, a former New York Times opera and music critic and pianist, offers readers a vivid romp through opera’s history and development, checking in on the most noted composers, performers, and performances along the way. This lively book should dispel any stereotypes about opera being dull or beyond the comprehension of everyday people. Schweitzer ranges from the first opera known to have been composed—the early 17th century L’Orfeo by Claudio Monteverdi—through great Romantic era pieces like Carmen by Georges Bizet to contemporary works by composers like Philip Glass. The author provides us with riveting stories of the high—and low—moments in opera’s dramatic history, including the initial hostility of audiences toward Gioachino Rossini’s now-classic The Barber of Seville, and the rising and falling critical reputations of composers such as the near-contemporaries Richard Wagner and Giuseppe Verdi, bringing considerable wit and humor to the task. 4. Take a tour with an iconic guideIn 1984, beloved radio personality Karl Haas published Inside Music: How to Understand, Listen to, and Enjoy Good Music. Haas, who died in 2005 at age 91, had become an informal instructor in classical music for people all over the world through his program called Adventures in Good Music, broadcast by numerous public radio stations. Inside Music brings Haas’ distinctive blend of erudition and lively, pun-filled sense of humor to the fore, providing a friendly guided tour through the history and composition of great works. The book has been through multiple editions and remains in print under the Anchor imprint. Generations of readers have found it an indispensable first survey of its subject. 5. Enjoy a master classThe Lives of the Great Composers by Harold Schonberg, originally published in 1970, is another older classic widely read and loved by amateur and professional students of music alike. Still available in an updated edition published by W. W. Norton & Company, the book offers detailed but easily digestible biographical portraits of composers from the Baroque era to the minimalists, tonalists, and experimentalists of the 20th century.

The author additionally covers the lives and contributions of female composers such as Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel, the sister of Felix Mendelssohn. This makes a welcome addition to our expanding knowledge of composers who have remained underappreciated for generations due to their gender. Schonberg, who died in 2003, was another New York Times music critic, and the first person ever to earn a Pulitzer Prize for music criticism. Since ancient times, archeologists have discovered relatively few musical instruments and fragments of musical instruments. Yet each one of them tells us something important about the musical heritage of humanity. Learning about each of them can play an important role in teaching today’s young students about the joys and possibilities inherent in making music. A number of contemporary musicians recreate ancient instruments according to the best-available historical and musical information. Such instruments may be displayed in a museum, brought to school as a learning experience, or played in a performance. Here are a few of those instruments: 1. LyrePerhaps the ancient instrument that remains best-known to today’s audiences is the lyre. The stringed instrument was popular in ancient Greece. In fact, some commentators have described the lyre as the instrument that best illustrates the traditional character of Greece. Like the piano today, it was typically a central part of a student’s musical education. An ancient musician would play the lyre alone or as an accompaniment to singing or a poetry recital. The standard form of the lyre was two stationary upright arms—sometimes horns—with a crossbar connecting them. The instrument would be tuned by means of a set of pegs, which could be made of ivory, wood, bone, or bronze. Stretched between the crossbar and a stationary bottom portion were seven strings that varied in thickness, but which were typically all of the same length. A musician either plucked the strings by hand or used a plectrum. Closely related stringed instruments included the kithara, which also had seven strings; the phorminx, which had four; and the chelys, fashioned from tortoiseshell. In fact, ancient writers tended to use these four instruments interchangeably in variant retellings of different myths. A typical Greek myth states that the messenger god Hermes originated the lyre. Hermes instructed the sun god Apollo in how to play the instrument. Apollo became a master lyre player who in turn instructed the gifted musician Orpheus. 2. Syrinx The syrinx, also known as the Pan’s syrinx, the Pan flute, or—in modern times—the panpipes, is a wind instrument associated with the shepherd god Pan, as well as human shepherds. It was considered a rustic—not an artistic—instrument. The Greeks were likely the first to make use of the syrinx, which was made of between four and eight sections of cane tubing of different lengths, bound together with wax, flax, or cane. A syrinx player could produce a range of rich, low tones by blowing across the tops of the cane tubes. Thousands of years of Greek art frequently show images of the syrinx. Artistic depictions of mythological figures such as Hermes, Pan himself, and the satyrs—half goat, half man—often show them playing the syrinx. 3. SistrumThe sistrum was a percussion rattle known to be used by the ancient Egyptians and Greeks. It enabled musicians to create a backbeat accompaniment to the instruments carrying the tune, particularly during religious ceremonies. A sistrum could be fashioned from wood or clay, as well as metal. Its percussive pieces consisted of horizontally arranged bars and the moveable jingle parts assembled along them. The sistrum had a handle attached to this framework, and a musician shook it just like a rattle. The sistrum was chiefly associated in Egyptian culture with the mother goddesses Hathor and Isis. Ancient artwork shows musicians playing the sistrum in statues and figures on pottery. 4. Aulos and Double AulosThe aulos, a reed-blown wind instrument that resembles a modern flute, was among the most commonly used instruments in ancient Greece. Associated with the god of wine, Dionysos, it was a frequent accompaniment to athletic festivals, theater performances, and dinners and events in private homes. Like the contemporary flute, the aulos consisted of several individual sections that locked into place together. It could be made of bone, ivory, boxwood, cane, copper, or bronze. It also featured several different types of mouthpieces, which could produce various pitches. The ancient Greeks also made use of the diaulos—the double aulos—which was made by affixing two equal-sized or different-sized pipes together at the mouthpiece. If the two pipes were of uneven length, the resulting sound was enriched with a supporting melody line. The Greeks also sometimes used a strap made of leather to secure the pipes to a musician’s face for ease of playing. With its deep, resonant sounds, the diaulos typically functioned as a support for all-male choral performances. 5. Xun Among the oldest-known ancient Chinese musical instruments is the xun, a type of vessel flute that researchers believe dates back more than 7,000 years. Historians believe that the xun was among the most popular instruments of its time.

The xun was typically made of pottery clay and often featured depictions of animals. Offering a one-octave range, it was fashioned into the shape of an egg with a flat bottom and a number of fingerholes along its body. A player could produce sound by blowing across the top mouthpiece. Examples of the xun have been excavated at archeological sites in various parts of China, with some of the later finds formed to resemble fruits or fish. Some of the more intricately decorated xun created over the centuries have become highly prized pieces in museums and private collections. Ancient writings mention the xun, often accompanied by the chi, which was a side-held flute typically made of bamboo. Musicians usually employed the xun as a component of a traditional ritual ensemble. The xun was regularly used until about a century ago, and has recently experienced a revival. A contemporary version, with nine holes is used in some Chinese orchestras today. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City is the home of countless artistic, historic, and cultural treasures from all over the world. Music educators, music students, and their families traveling to the city should all consider putting the Met’s vast collections of musical instruments on their day-trip itineraries. The museum’s 5,000 instruments, with some more than 2,000 years old, come from all over the world. Curators have selected each one for its visual appeal and the quality of its sound, as well as for its importance in the entire history of humanity’s interactions with music. Here are notes on only a few of the impressive items owned by the Met. 1. One of the first pianosThe highlights of the Met’s music collections include a grand piano dating from about 1720 in Florence, Italy, and constructed by Bartolomeo Cristofori. Scholars generally credit Cristofori with the invention of the piano, based on his functional hammered keyboard. The Met’s Cristofori piano is the oldest of the three known to be in existence, and it is fashioned chiefly from cypress wood and boxwood. Cristofori’s design for his hammer mechanism was so well-constructed and musically flexible that no other inventor was able to devise a comparable one for 75 years. Many of today’s musicologists believe that the rich harmonies and tonal complexity of the contemporary piano trace directly back to his instrument. 2. A symphony in stringsThe Met is home to a viola d’amore made by Giovanni Grancino in Milan in 1701. With the exception of the legendary violin-makers of the town of Cremona, Grancino is often viewed by musicologists as the foremost practitioner of his art working in the early 18th century. The viola d’amore is one of the members of the viol family, which includes the violin. The Met’s example is created out of spruce, ebony, and maple woods, as well as iron and bone. Grancino’s instrument features metal strings, a characteristic of early viola d’amores. Later pieces went on to use sympathetic strings. The metal strings were noted for giving the instrument its “sweetness” in sound. Several other similarly shaped Grancino viola d’amores survive, with varying numbers of strings and in different sizes. In fact, his instruments were distinguished in part by the lack of standardization in their construction. Of the surviving pieces, one has four strings, two have five, and the Met’s example, in particular, underwent a reconstruction to restore it with its original six strings. 3. A bell that rings in ceremony and spectacleA Japanese densho circa 1856 can be found among the Met’s collection. This leaded bronze ceremonial bell was used originally as a call to Buddhist prayer. With its depictions of dragon heads, flames, and a delicate chrysanthemum denoting the striking surface, this densho displays symbols common to many East Asian cultures. Japanese kabuki theater still sometimes incorporates the sound of a densho into performances. 4. A magical fluteAn elegant little transverse (side-blown) flute created by Claude Laurent in 1813 also adorns the Met’s musical collections. Fashioned of glass and brass in Paris, the flute incorporates its designer’s skill as a watchmaker into its construction. Laurent employed various kinds of glass, as well as lead crystal, to create flutes in multiple colors. Made from delicate white crystal, the Met’s flute features four brass keys. With his other flutes, Laurent followed Theobald Boehm, the early 19th-century inventor and musician responsible for the flute as we know it today, to fashion flutes with greater complexity in their keying arrangements. After Laurent died, interest in his type of crystal flute fell away. Even so, his construction of keys affixed to “pillars” on the instrument remains a standard component of flute design today. 5. A guitar beautiful in sound and formAn intricately ornamented guitar constructed toward the close of the 17th century offers visitors to the Met a look at the care an instrument-maker from the past could lavish on one of his creations, from an aesthetic, as well as a functional, point of view. Scholars attribute this guitar to Jean-Baptiste Voboam, who was one of an entire family dynasty of stringed instrument-makers working at a time when France was just beginning to come into its own as a source of fine guitar-making. Whoever its maker may have been, its use of tortoiseshell, ivory, ebony, mother-of-pearl, and spruce make this guitar a particular pleasure to view. 6. A drum with many beatsA double-headed tánggǔ drum produced in 19th-century China during the Qing dynasty also adorns the Met’s collections. This lacquered example—fashioned from teak, brass, and oxhide—comes from Shanghai. Depending on where on the surface the player strikes the oxhide, the barrel of the drum will produce a rich variation of musical volume and tone.

This type of drum typically found its way into both Buddhist ceremonial activities and the performing arts. Today’s Chinese orchestras often make use of a modern-day form of the tánggǔ. |

Photo used under Creative Commons from Marina K Caprara

RSS Feed

RSS Feed