|

Movie theme songs can serve as touchstones for personal memories, define key cultural moments, and even become part of history. The following are a few of the greatest and most popular theme songs that have been made famous on the big screen. All of them can evoke the spirit of the movies they defined with just a few notes. 1. “As Time Goes By" “You must remember this.” As sung in the 1942 film Casablanca by performer Dooley Wilson, “As Time Goes By” carries with it a bittersweet sense of longing for the past, along with resignation and affirmation of the power of an enduring love. We all know the story: Humphrey Bogart plays world-weary cafe owner Rick, existing on the periphery of the fighting in Casablanca, Morocco, during World War II. His former love Ilsa (Ingrid Bergman) suddenly appears, begging him for help in getting her husband, a resistance fighter played by Paul Henreid, to safety in Lisbon. “As Time Goes By” was Rick’s and Ilsa’s song, and they both request to hear it, becoming immersed in the glow of the past. Torn between love and duty, Ilsa and Rick enjoy a few stolen moments before she joins her husband in order to help support his work. The song was actually repurposed for the film. Songwriter Herman Hupfeld originally wrote it for a now-forgotten 1931 musical, and pop icon Rudy Vallee recorded it. Now honored with a place in the Songwriters Hall of Fame as a “Towering Song,” “As Time Goes By” still reminds us that “The world will always welcome lovers.” 2. “Moon River”Audrey Hepburn remains a legend, for her grace, style, and warm personality, as well as her role as a UNICEF Special Ambassador. Hepburn’s most memorable performances include playing the lead role in the film Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) as Holly Golightly, a madcap young woman in New York who makes her way through life by mooching off of the admirers she gathers, while she lives a vivid fantasy life. “Moon River,” with wistful lyrics that perfectly complement the soulful flow of its music, is the song Hepburn’s character sings, playing her guitar while musing and dreaming on her fire escape: “Wherever you’re going, I’m going your way.” The song, for which Johnny Mercer wrote the lyrics to Henry Mancini’s music, won an Oscar for Best Original Song, followed by two Grammys. The movie’s storyline, with its twists and turns of plot as Holly’s past threatens to shatter the genuinely tender love that develops between her and her handsome neighbor (played by George Peppard), works the song into its most vivid and heartbreaking moments, until these two lost souls find each other again and are “off to see the world” together. 3. “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head”The 1969 western “buddy” film about Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid starred Paul Newman and Robert Redford in a fictionalized version of the life stories of the famous outlaws, and Katharine Ross played their mutual love interest. The film won multiple Oscars, including one for William Goldman’s witty, highly quotable script. The film also won an Oscar for Best Original Song for Burt Bacharach and Hal David’s “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head.” The simple lyrics and joyful tune, performed in the film by BJ Thomas, accompany a now-iconic moment in the film, when Newman and Ross ride together on a bike down a dirt road through an orchard. The song lifts the scene into a depiction of pure happiness about being alive, despite the “raindrops” that may fall. It’s a pick-me-up song whose rhythms and lyrics have made it a favorite among young performers over the decades, even while adults get its more poignant references to keeping the “blues” at bay. 4. “9 to 5" In 1980, singer-songwriter Dolly Parton joined actress Jane Fonda and comedian Lily Tomlin in one of the first female “buddy” comedies ever. The movie 9 to 5 also delivered a stinging message of social commentary about women’s rights and the fair treatment of employees. The movie’s eponymous theme song, written by Parton, remains a popular anthem for people struggling for dignity in the workplace. The storyline involves the three friends, who all work as secretaries, in an epic take-down of their sexist tyrant of a boss who denies women promotions while using and abusing them for their abilities. Ultimately, he is dethroned and the three women are finally recognized for their talents. The song’s lyrics ingeniously weave social satire with a buoyant can-do attitude, as the music bounces through Parton’s descriptions of stumbling through another day fraught with ambition denied and dreams shattered, but still with the confidence that there are some things no one can take away. As Parton reminds us in the song’s refrain: “There’s a better life.” 5. “Happy”Once you’ve heard the song “Happy,” it will probably be impossible to get its upbeat and danceable rhythms out of your head. Pharrell Williams’ hit song seems to be an embodiment of dance itself.

The song was a central part of the 2014 animated film Despicable Me 2, the second in the already-classic series of movies about the villain-turned loving father Felonious Gru (voiced by Steve Carell), his adopted children, and the hordes of bright yellow, exuberantly chaos-making Minions. “Happy” went on to become the biggest-selling song of the year. Don’t we all want “a room without a roof?” The playful visual imagery of the song also seems to hold deeper meanings about an acceptance of life’s wanderings, whether by hot air balloon or otherwise, and always with the attitude that “happiness is the truth.” “Happy” will bring back a whole wealth of fun family memories for many people. It will also be part of the joyous history of the life of the late civil rights hero and United States Congressman John Lewis. Vital and life-affirming to the end of his 80 years, Lewis was captured on a now-viral piece of campaign film footage moving with confidence and fluid grace, as he danced alongside supporters of then-Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams to the beats of “Happy.” We may not often think of the great composers and musicians of the past as heroes in the sense of being physically brave, or courageous in the sense of putting everything on the line for ideals they believed in. However, behind the great music we know, there are also personal stories of heroism, dedication to causes beyond the self, and steadfast love and kindness that deserve our attention and respect, particularly in today’s chaotic and divisive world. Here are only a few of these heroes from our musical past. Clara Schumann (1819 - 1896)Clara Schumann’s husband, German Romantic composer Robert Schumann, is far more widely known. He created magnificent, intricately virtuosic symphonies and a rich collection of songs and piano pieces, many of them written expressly for her. However, Clara was a highly gifted musician and composer in her own right, and we can attribute her historical neglect to long-standing sexism. In her youth, she was renowned all over Europe as a child prodigy of the piano. Felix Mendelssohn conducted the premiere of her piano concerto, with teenage Clara at the keyboard. She would go on to compose solo pieces and chamber music, and to teach at Leipzig Conservatory. Remarkably, she did all this while caring for her increasingly ill and troubled husband and their many children. The Schumanns had a Romeo-and-Juliet love story. Robert proposed to Clara when she was 18, but her abusive and tyrannical father, Friedrich Wieck, forbade the match. Robert trailed her across Europe as she performed, hoping for a few chance hours together. Friedrich controlled every aspect of his daughter’s life, so she took matters into her own hands and sued him in court. Before the court rejected his claims, her father attempted to gain control of all her concert earnings. He confiscated her piano, stole her letters, and wrote scurrilous slanders against Schumann. Robert and Clara emerged the winners in court and married in 1840. In 1849, Europe was in tumult as revolutions swept the continent, eventually touching the young Schumann family in Dresden. Clara was seven months pregnant, and outside their home peaceful protestors were being gunned down in the streets. Walking through the town the morning after a tense clash, she saw the corpses of those killed and noted the troops knocking on every door to whisk away every able-bodied man to the fighting. Robert Schumann had already shown signs of his severe and life-long mental illness. Clara, desperate to protect him, told the militias he was away from home. To ensure his safety, she devised a plan to spirit him out of Dresden. She left three of her young children at home with a caregiver, to avoid suspicions of the whole family fleeing. Then, she got Robert, their seven-year-old daughter, and herself to the closest train station, talking her way through tense encounters at guarded checkpoints. With Robert and young Marie safely eight hours away, concealed with friends in a small village, Clara returned to Dresden—hiding to avoid detection by patrols of men wielding farm scythes as weapons—and rescued her remaining children from danger. Maurice Ravel (1875 - 1937)French composer Maurice Ravel is likely best known for the orchestral piece Boléro. The composition is used so often in films and television that its rich, stirring music has almost become a cliché. Ravel’s technical mastery, finely tuned sense of melody, and fluidly expressive style are also evident in Pavane for a Dead Princess, his opera The Child and the Enchantments, and the ballet Daphnis and Chloe. Ravel was not a very political man; his personality has been described as intellectual and a little aloof. But in 1914 at age 39, he tried to enlist in the French air force, hoping to serve his country after Austria-Hungary’s declaration of war. Ravel had kept himself anchored to his music for most of his life, separated from the troubles of the rest of the world, but now he felt he needed to become a man of action. Initially, he was rebuffed when the air force thought him too old and unfit. Ravel was a short, slight man who weighed just 91 pounds. However, he was enraged by the deaths of his friends in uniform and wouldn’t take no for an answer. He drove army gasoline trucks near Verdun, where 40,000 men every month were being slaughtered. Hemmed in by enemy fire, he once had to hide in the forest for 10 days. Discharged after contracting dysentery, he was sent home. Critics then and now have often pointed to the violent, clashing rhythms of La Valse (“The Waltz”) as his musical declaration of war against the Viennese enemy. He also composed the piano suite Le Tombeau de Couperin and dedicated each movement to a friend who had died in combat. Benny Goodman (1909 - 1986)Beloved as “the King of Swing,” Benny Goodman was one of the greatest jazz clarinetists and bandleaders the world has ever known. His all-consuming devotion to perfecting his art led to a historic 1938 Carnegie Hall concert in which, for the first time ever, a concert hall audience was treated to a full program of swing music.

This New York-born son of Jewish immigrants from Tsarist Russia started out with a classical training, then quickly became absorbed into the Dixieland and jazz music scenes. He accompanied Billie Holiday in what are now considered landmark performances. Goodman put together his own band in 1934 and went on to create—in solo performances and as a bandleader—what would become some of the 20th century’s most memorable live performance hits and recordings: “Stompin’ at the Savoy,” “Moonglow,” “Let’s Dance,” and scores of others. That 1938 Carnegie Hall concert was historic for another reason, too: Goodman insisted on performing with his racially integrated band. This arrangement was almost beyond the ability of anyone at that time to comprehend. Most performance spaces were strictly segregated. Throughout his career, Goodman worked with integrated ensembles. In the early 1930s, he had at first hesitated to bring Black performers into his band, but his merciless search for the best sound and his commitment to acknowledging common bonds of humanity won the day. One of the first events in American public life to break the color barrier, that initial Carnegie Hall concert featured half a dozen Black musicians, including Lester Young on sax, Lionel Hampton on the vibraphone, and Count Basie and Teddy Wilson on piano. Hampton later recalled that Goodman’s decision to work alongside Black musicians came not from a desire for fame or money, but from the bandleader’s heart. He recalled Goodman saying that the “white keys and the black keys” just needed to be allowed to harmonize. Musicians around the world have paid tribute to civil rights leader and human rights hero Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The tributes began immediately after his death by an assassin’s bullet on April 4, 1968, in Memphis, Tennessee, and have continued over the decades since then. Here are a few of the songs honoring Dr. King that have conveyed grief, remembrance, inspiration, and hope to millions of Americans, as well as to people around the world struggling to assert their rights amid bigotry and violence. 1. “Abraham, Martin and John”“Abraham, Martin and John,” with words and music by rock musician Dick Holler, was written as a tribute to Dr. King and to presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy, who was assassinated just shortly after King was gunned down. It was a tumultuous time, and communities nationwide—the black community in particular—were torn apart by anger and grief. Holler’s spare, repetitive chords, and gentle, evocative, and simple words—as originally recorded by singer Dion DiMucci—seemed just right for the moment. The song references, in turn, President Abraham Lincoln, President John F. Kennedy, King, and Robert Kennedy, each of whom “freed a lot of people” but died violent, untimely deaths amid cataclysmic events that would change the course of history. The song’s four verses are identical except for the name of each man. Each one asks the listener if anyone has seen “my old friend Abraham,” “my old friend John,” and so on. The concluding words paint a picture of the four men walking side by side over a hill together. The words and sentiments may be considered old-fashioned—even simplistic—to some listeners today. But for many who were alive at the time and looked up to King and the Kennedy brothers as the best of America, they can still summon tears and—often—a smile of wistfulness for the bright future that these men stood for that remains only partially realized. 2. “Happy Birthday”“Happy Birthday” by Stevie Wonder is a song written for a didactic purpose, but one whose lyrics and music still bring joy to audiences who may not even be aware of their original meaning. Wonder, the blind superstar singer-songwriter whose poetic lyrics and musically complex and ingenious melodies embody the joys and struggles of the 1960s and ‘70s, has always been an activist. So, he wrote “Happy Birthday” in 1981 as part of a campaign to get King’s birthday declared an official national holiday. At the time, there was vigorous opposition from conservative politicians and interest groups to a federal holiday honoring King. Wonder’s up-tempo beat and lyrics celebrate King and ask how anyone could oppose the national recognition of “a man who died for good.” Wonder’s lively refrain of “Happy Birthday to ya!” is still very danceable and much deserving of celebration. In 1982, Wonder joined King’s widow, Coretta Scott King, in delivering a petition with 6 million signatures on it in support of the holiday directly to the Speaker of the United States House of Representatives. The following year, President Ronald Reagan signed into law a bill declaring Martin Luther King, Jr. Day a federal holiday to be observed every third Monday in January, beginning in 1986. 3. “Pride (In the Name of Love)”“Pride (In the Name of Love)” by the Irish rock group U2 was released in 1984 as the lead single on the album “Unforgettable Fire.” The band’s lead singer, Bono, initially put together a set of lyrics intended to condemn the militaristic focus of the United States under President Ronald Reagan’s administration. But after a 1983 visit to an exhibit honoring King’s legacy at Chicago’s Peace Museum, Bono began crafting the song to highlight King’s achievements, as well as those of other martyrs to the cause of peace throughout history. The finished lyrics echo King’s own phrases, such as “Free at last,” and “One man come in the name of love.” The phrase “pride” in the title is used in two ways in the lyrics. One kind of “pride” that Bono refers to is the pride of aggression and violence. The second is the kind of pride moral heroes like King embodied, pride in being on the side of justice and freedom for all people. 4. “The King”Pioneering New York hip hop composer and performer Grandmaster Flash, with his group the Furious Five, produced another moving tribute to King, with a song simply titled “The King,” which was featured on the 1988 album On the Strength. The song’s beats and rhythms alone serve as an example of Grandmaster Flash’s classic and fresh musicianship, even as its lyrics provide a lasting artistic memorial to King, a man who “brought hope to the hopeless.” “His name is Martin Luther King,” and he dedicated his life to “making freedom ring,” the rap song proclaims. It relates how King, who was fearless in his convictions, was vilified and persecuted as a black man taking constructive action for freedom for all blacks, and it laments the fact that too many turned away from King’s message of peace and hope, during his lifetime and after. 5. “A Dream”“A Dream,” which is rapper Common’s 2006 tribute to King, samples the words of the hero’s most famous speech. The music video for the song incorporates historical footage of King delivering the speech at the March on Washington in 1963.

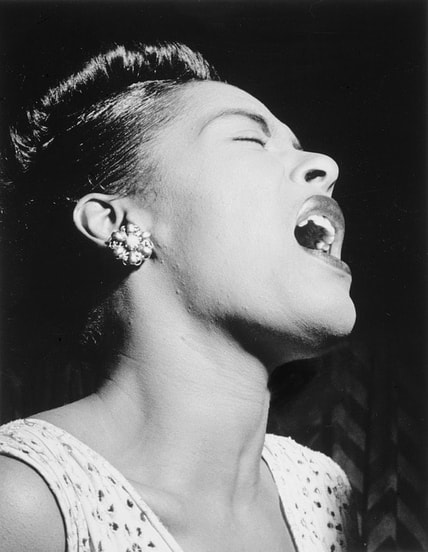

Common weaves King’s original words and story (“I have a dream”) into his own perspective (“I got a dream”) as a 21st century black man “born on the blacklist” to struggle against enduring racism, but working to find the hope that still endures through the inspiration he draws from King’s words. Common’s performance, featuring fellow American rapper will.i.am, elaborates on King’s words “one day” throughout its lyrics, and adds, of dreams, “I still have one.” In 1939, Nazi Germany began an international war based on mistaken, hateful, and deadly ideas about a “master race.” That year, the United States also struggled under the strain of its own racism, with the struggle playing out in the world of music through now-iconic performances by Black American singers Billie Holiday and Marian Anderson. Lady Day fights to perform a haunting song Billie Holiday Billie Holiday A legend during her short lifetime, Billie Holiday was one of the most gifted, original singers the world of jazz has ever known. Her 1939 recording of “Strange Fruit” became an indelible part of music history—and the civil rights movement. This tragic, deeply evocative song was written and sung as a deliberate protest against lynching, although it never directly refers to it. But the meaning of “strange fruit” hanging from Southern trees is agonizingly clear, as is the song’s graphic rejection of white supremacy. Abel Meeropol, a poet, songwriter, activist, and teacher at New York’s DeWitt Clinton High School, was unable to put a photograph of a lynching he’d seen out of his mind. He wrote an impassioned poem, later published in a teacher’s union magazine. He set the words to music, and one evening at the Greenwich Village club Café Society, he offered the song to Billie Holiday. It took great courage for Meeropol, a white Jewish man and the son of immigrants, to write the song, and for Holiday, a well-known performer but still a Black woman in a time of often-vicious racism, to perform it. Holiday’s goddaughter later told an interviewer that when her godmother performed the song in front of white audiences, the effect was “viscerally shocking.” Radio stations were afraid to play “Strange Fruit.” Clubs tried to get Holiday to leave it out of her sets. This was a time when performers and activists were often accused of being Communists, and when people who struggled with addiction, like Holiday, were treated with public scorn or jailed. Government agents threatened Holiday with arrest if she continued to perform “Strange Fruit.” She refused, and it became her signature song. For years, Federal Bureau of Narcotics chief Harry Anslinger harassed and stalked Holiday, trying to arrest her for drug use. She continued to perform “Strange Fruit,” even for white audiences in the Deep South. Anslinger, whom history reveals as a racist with a hatred for people with addictions—in particular Holiday—had her arrested while she was being treated in the hospital for liver disease. Anslinger refused to allow her to continue methadone treatment to wean her from her heroin addiction. Holiday died soon after, in 1959. Biographers have commented that it’s not too much to say that her insistence on performing “Strange Fruit” killed her. In 1999, Holiday’s first studio recording of the song was selected by Time magazine as its choice for the song of the century. Marian Anderson’s quiet dignity breaks musical color barriers Marian Anderson | Image courtesy GPA Photo Archive Marian Anderson | Image courtesy GPA Photo Archive The year 1939 was also a watershed one for Marian Anderson, the world-famous operatic contralto with the kind of voice conductor Arturo Toscanini praised as coming along only “once in a hundred years.” As a Black woman, Anderson had been denied access to perform at Constitution Hall in Washington, DC, a segregated venue owned by the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). So, on April 9, in a concert that stands as a focal point of the civil rights movement, she performed on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial instead. Anderson later remembered her terror before the event. Although she had performed to acclaim across Europe and the United States, this crowd of 75,000 would be the largest she had faced. But she wrote that she “could not run away” from what she knew she needed to do. The evening was chilly, and Anderson, a regal silhouette standing in front of the statue of another monumental figure, hugged her fur coat around her. She took a deep breath and began her performance with the patriotic song “America,” singing, “My country, ‘tis of thee” in a strong, resolute voice, with phrasings filled with power and sweetness. Accompanied by a single pianist, Anderson continued her half-hour concert with “O Mio Fernando,” an aria from Donizetti’s opera La Favorite, followed by Schubert’s arrangement of “Ave Maria,” Henry Burleigh’s arrangement of the traditional spiritual “Gospel Train,” the Edward Boatner spiritual “Trampin’,” and “My Soul’s Been Anchored in the Lord.” Notably, this last piece is a spiritual arranged by Black American composer Florence Price, whose large body of work was only recently rediscovered. The announcer broadcasting the event to an audience of millions stated that Anderson was not able to find an auditorium large enough to fit the many people who wanted to hear her. But that wasn’t it at all. Howard University had invited Anderson to perform in its concert series, but because of her status as an international icon, the school needed an outside venue that could accommodate the anticipated audience. Constitution Hall seemed the ideal choice, but the DAR’s contract specified that the space was only open to white performers. And, ironically, the nation’s capital itself was part of the segregated South. People across the country were outraged. Eleanor Roosevelt resigned her DAR membership, stating that she could not in good conscience remain a member. The DAR refused to back down, even for the First Lady. NAACP executive secretary Walter White had the idea of performing at the Lincoln Memorial. As a national monument, the property was under federal control. So, it was Interior Secretary Harold Ickes who led Anderson to her place on stage. In introducing her, Ickes told the desegregated audience, “Genius draws no color lines.” Marian Anderson would live to be 96 years old, but the Lincoln Memorial concert would always be the defining moment of her career. Anderson was not a vocal civil rights activist, but she believed that if she performed with grace and dignity, that would be enough to help shatter bigoted stereotypes and elevate future prospects for Black Americans. But music historians note that her concert on those steps that spring day in 1939 was the start of a new era for Black musicians and performers. It was also yet another early event that would help ignite the passion of the civil rights movement in the coming decades, and one that remains a source of inspiration and pride. Many young people—and even many adults—are not aware that many of the world’s foremost musicians and performing artists have lived with one or more disabilities. Here are six of some of the best-known singers, songwriters, and performers of the 20th and early 21st centuries who can serve as vivid role models of creativity and perseverance for musicians of all types of ability: 1. Django Reinhardt Django Reinhardt (1910 - 1953) was a Roma musician born in an itinerant camp near Paris. As a young man, he became skilled on banjo, violin, and guitar, but at age 18 received severe burns from a caravan fire. The accident left him with one leg paralyzed and with a badly damaged hand. He relearned how to play guitar with his hand injuries. He also relearned how to walk using a cane. At only 24 years old, he joined with violinist Stéphane Grappelli to co-lead the Quintette du Hot Club de France, and later toured with Duke Ellington. A master of improvisation, Reinhardt is beloved today by scholars and music-lovers for the exceptional originality of his compositions. He is honored as one of the most richly creative spirits in the history of jazz. 2. Hank Williams Hank Williams (1923 - 1953) was one of the world’s major country music stars, known for his talents as a singer, a guitarist, and a songwriter. Williams gave intense, lyrical performances of songs like “Your Cheatin’ Heart,” “Howlin’ at the Moon,” “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” and “Lost Highway.” After he joined Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry he catapulted to international fame. His songs remain iconic and deeply moving expressions of the best of American popular music. Williams was born with spina bifida oculta, a malformation of the spinal column that typically goes unnoticed, but that in his case resulted in lifelong chronic pain. Williams was a driven composer and performer who threw himself completely into his music. His use of drugs and alcohol intensified after a failed surgery to repair his spinal defect, and he died of a heart attack at age 29. In 2010, Williams received a posthumous Pulitzer Prize citation for the extraordinary technical and emotional quality of his compositions, and for his role in transforming American country music on the world stage. 3. Rosemary Clooney Rosemary Clooney (1928 - 2002) may be more famous today as the aunt of movie superstar and humanitarian George Clooney. But in the mid-20th century, the Irish-American jazz and pop singer was among the world’s best-known female vocalists, and was widely beloved by fans the world over. She had an extraordinarily rich vocal quality and an unbeatable sense of timing and phrasing. Her 1951 recording of “Come On-a My House” topped the charts in its day, and remains popular. After the assassination of her friend Robert F. Kennedy, a shock that was exacerbated by drug addiction, Clooney was hospitalized for several years. She relied on her music to help pull herself through. She battled bipolar disorder for decades, writing courageously about her experiences with the condition in her 1977 autobiography, This for Remembrance. The year that she died, she received a Grammy Award for lifetime achievement. 4. Itzhak Perlman Itzhak Perlman (born 1945) is an Israeli-born virtuoso of the violin. His range of interpretation and mastery of the technicalities of musicianship have caused numerous critics to rank him among the greatest musicians in history. Perlman contracted polio as a 4-year-old, and as a result he uses crutches to help him walk. As a teen, he made his debut at Carnegie Hall in New York. In the decades since, Perlman has played and conducted with major orchestras around the world. He has recorded an extensive catalog of classical, jazz, traditional Jewish, and theatrical music, including the solo violin portions of John Williams’ score for the film Schindler’s List. He has earned 15 Grammy Awards to date. Perlman, a vocal advocate for music education and for people with disabilities, also received a Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2015. 5. Diane SchuurDiane Schuur (born 1953) has been blind from birth due to a condition called retinopathy of prematurity. She is also one of the leading jazz vocalists in the world today as well as an accomplished pianist. Schuur, who began performing for family and friends while still a preschooler, went on to a genre-bending recording and performing career, earning two Grammy Awards to date. Heavily influenced by jazz legends like Dinah Washington, Sarah Vaughan, and the blind pianist George Shearing, Schuur rose to fame in the mid-1970s. Her smooth, effervescent interpretations of classic and contemporary songs made her a hit with the public, with musicians like Stan Getz and Stevie Wonder championing her talent. In 2020, Schuur released a new album, Running on Faith. It includes interpretations of her favorite standards, including a thrilling rendition of Washington’s signature song, “This Bitter Earth.” In 2000, Schuur was honored with a Helen Keller Achievement Award from the American Foundation for the Blind. 6. Stevie Wonder Stevie Wonder (born 1950) needs no introduction, even to music fans born long after the peak of his fame. Born Steveland Morris, the now world-famous singer received too much oxygen in an incubator as a newborn, which resulted in permanent blindness. As a young boy growing up in inner-city Detroit, Wonder idolized musicians like Ray Charles—who was also blind—and learned to play multiple instruments.

When he was only 11, Wonder was discovered by singer Ronnie White of The Miracles, a popular Motown singing group. At 12, he cut his first album for Motown Records, beginning a varied career of brilliant performance and composition that endures into the present. Wonder’s work ranges from lighthearted love ballads like “My Cherie Amour” to powerful, driving, musically intricate pieces like “Superstition,” to songs that capture the chaos, deprivation, passion, and hope of the social changes of the 1960s and early ‘70s. Albums like Songs in the Key of Life (1976) have achieved milestone status among music critics, and Wonder has earned a total of 25 Grammys to date. The Civil Rights movement produced a treasury of songs whose messages and musical quality continue to move audiences today. Here are the stories behind just three of these, all composed and notably performed by musicians of African-American descent: 1. “Lift Every Voice and Sing" “Lift Every Voice and Sing” is also known as the “Black American National Anthem.” The words, by poet and later NAACP leader James Weldon Johnson, were set to music by the poet’s brother, John Rosamund Johnson. The brothers hoped the song would help heal the wounds inflicted on the African-American community by generations of brutality. James Weldon Johnson also served as principal at the segregated Stanton School in Jacksonville, Florida. In 1900, students there gave the song its first public performance in observance of Abraham Lincoln’s birthday. In 1919, it was adopted as the official song of the NAACP, and black church choirs across the South made it a staple of their repertoires. One person at the time described it as a “collective prayer.” By the 1930s and 40s, people hungry for freedom around the world were singing it, and it became an iconic song of the American Civil Rights movement. Johnson and his brother went on to write hundreds of songs for Broadway theaters. His rich treasury of individual work includes the 1927 collection God’s Trombones, featuring resonant, hymn-like poems such as “The Creation,” which retells the bible creation story in resonant, contemporary language. In recent years, “Lift Every Voice and Sing” has figured in Juneteenth celebrations, and has been covered by artists across the musical spectrum, including Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, Melba Moore, and the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. At the now-famous Wattstax concert in 1972, soul singer Kim Weston sang it and brought the audience to its feet after they had sat in stony silence during “The Star-Spangled Banner.” In 2018, Beyoncé performed it at Coachella for a largely white audience, a remarkable moment that helped raise awareness of the song’s key place in history. The fact that its lyrics alternate between being solemn with the knowledge of suffering and weariness, and being joyful with determination and hope for the future, is one reason it speaks to new generations. 2. “Freedom Highway" “Freedom Highway” is a song written specifically for a moment in time, to honor the Civil Rights struggle as it unfolded. It commemorates the freedom marchers across the segregated South in the 1950s and 60s, particularly those who in 1965 marched across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, on the way to Montgomery: “Marching freedom’s highway, I’m not gonna turn around.” Roebuck “Pops” Staples, leader and patriarch of the gospel group The Staple Singers, recalled the creation of the song just weeks after that historic march, in which protesters—including now-Congressman John Lewis—were brutally beaten by state troopers and an armed and angry mob on “Bloody Sunday.” Because of that march, Staples said, “words were revealed and a song was composed.” Staples made those remarks when introducing the song at Chicago’s New Nazareth Church on April 9, 1965. The church reverberated with the thundering righteousness of the song, which evokes the moral certainty of those involved in the fight for freedom and equality. The performance was recorded live and preserved for the future on an album reissued in 2015 as Freedom Highway Complete. The Staple Singers were the “First Family of Gospel.” “Pops” and his children Pervis, Yvonne, Cleotha, and Mavis worked together beginning in the late 1940s, building a blues-inflected, folk-gospel style drawing on the rhythms of Pops’ Mississippi Delta youth and driven by Mavis’ powerful soul vocals. The singers became close to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and commemorated him after his death with “A Long Walk to D.C.” Pops died in 2000, Cleotha in 2013, and Yvonne in 2018. Pervis left the group as a young man, but Mavis has kept up a solo career. Now past her 80th birthday, she issued the 2019 album We Get By. Additionally, she remains a staunch activist who sees the situation in the world today is very similar to the 60s. 3. “We Shall Overcome”The simple but powerful lyrics of “We Shall Overcome” speak not of oppression, but of hope: “Deep in my heart, I do believe, we shall overcome some day.” To this day, the song is one of the most recognizable of all those that defined the Civil Rights movement.

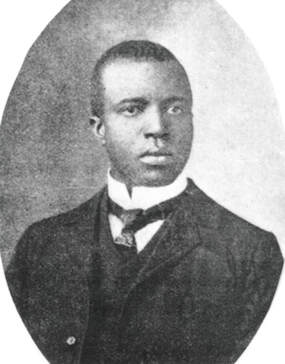

It has become an anthem of peaceful protesters all over the world. It has been song in Soweto Township in apartheid South Africa, in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, and most recently by protesters in Hong Kong fighting for autonomy from China’s authoritarian government and in the United States at #BlackLivesMatter protests. The origins of “We Shall Overcome” lie in a folk song (“I’ll be all right some day”) sung by American slaves. Its melody—both somber and soaring—is close to that of the spiritual “No More Auction Block.” In the hands of Methodist minister and gospel composer Charles Albert Tindley, himself the son of slaves, it became “I’ll Overcome Someday.” It was that version that became the basis for the one we know today. Tobacco workers in the 1940s began using the song during labor protests, its first political usage. They sang, “We will win our rights someday.” Zilphia Horton, a Tennessee music director and labor supporter, began teaching it in workshops. Folk singer Pete Seeger, sometimes erroneously credited as the song’s author, learned it from Horton. Seeger codified the title as “We Shall Overcome,” added new verses, and led it at numerous protests and rallies. In 1957, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., heard Seeger perform it at one of Horton’s workshops. On March 31, 1968, just days before his assassination, Dr. King used “We Shall Overcome” as the anchor and refrain of one of his most powerful speeches, saying, “We shall overcome because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” Despite centuries of injustice and limited opportunities, African-Americans have made countless contributions to science, medicine, public service, and the arts, among many other areas. American music, for example, would be far less rich, innovative, and memorable without the creative work of black composers. Scott Joplin, Duke Ellington, and Florence Price were gifted musicians. Additionally, their lives exemplify the obstacles 20th-century people of color had to overcome regardless of profession. Here’s what you need to know about their lives and work: Scott Joplin Image courtesy Wikipedia Image courtesy Wikipedia Around the turn of the 20th century, Scott Joplin’s innovations in syncopated ragtime music made him one of the most acclaimed and influential American pianists and composers. His “Maple Leaf Rag” and “The Entertainer” are now staples of the popular repertoire. Later audiences rediscovered this “King of Ragtime” through the use of his music in movies such as The Sting. The 1973 production won multiple Oscars, including one for Marvin Hamlisch’s adaptation and orchestration of Joplin’s music into its score. Joplin was born into a family of musicians in about 1867, probably in northeast Texas. He grew up in Texarkana and studied piano in his early teens. He performed in Chicago at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, and two years later studied music at a segregated school in Missouri. After his early work made him famous, Joplin moved to St. Louis. Hoping to reduce the prejudice shown by some critics to ragtime because of its African-American origins, Joplin published an instructional series called The School of Ragtime: Six Exercises for Piano. His ambitions as a composer of more traditional music led him to compose the opera A Guest of Honor and the ballet Rag Time Dance. Before his death in 1917, Joplin’s multi-genre operatic theater piece Treemonisha, whose African-American themes prefigured George Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess, was presented in a small-scale version. Critics have noted Treemonisha’s vivid blending of influences from Richard Wagner to Giuseppe Verdi to Tin Pan Alley. Notable recent stagings include a 2019 production at East London’s Grimeborn music festival. Duke Ellington Image courtesy Wikipedia Image courtesy Wikipedia Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington composed the score for Symphony in Black: A Rhapsody of Negro Life, which was also the film debut of then 19-year-old singer Billie Holiday. Revered as the most talented American jazz composer and conductor of his day, Duke Ellington wrote thousands of scores and is largely responsible for the distinctive sound of the Big Band era. Born in Washington, DC, in 1899 to a middle-class family that encouraged his artistic ambitions, Ellington studied piano at age 7 and began performing in ragtime bands in his teens. Working in New York City from 1923, he eventually assembled a 14-piece orchestra. Ellington’s band became a fixture at Harlem’s Cotton Club in the 1920s and ‘30s, and he hired musicians who were themselves major figures in the development of jazz. This group of musicians became a wildly popular touring ensemble, appeared in multiple films, and went on the road in Europe from 1933 to 1939. Ellington’s music, and swing and jazz in general, were popular among anti-Nazi German youth. As a result, he was among the many black performers banned from working in Germany after the mid-1930s. However, at that time, the Cotton Club was an all-white establishment as far as patrons were concerned, and black musicians had to enter by the back door. While on tour in the United Kingdom in 1933, Ellington’s troupe was turned away from several hotels, and he suffered many other such slights on tour in the United States. This inspired him to begin working on behalf of the NAACP’s fight for racial justice. His extraordinary talent and personality forced white critics and audiences to take African-American music and performers seriously. By the late 1930s, Ellington had begun composing long-form pieces, and the 1940s saw him compose a string of fast-tempo hits and pieces rich in tonal color. Ellington also expanded his talents into theater scores, including the 1964 production My People, a tribute to the Civil Rights movement. Ellington’s band continued touring the world with him for many years. Many of the same performers remained with him for four decades or more. His regal demeanor and charm continued to draw audiences until shortly before his death in 1974. Florence Price Image courtesy Wikipedia Image courtesy Wikipedia Florence Price is one of the few African-American female composers of symphonic music whose work achieved significant recognition from white audiences during her lifetime. She was the first black woman to have her work performed by a well-known orchestra. In 1933, the Chicago Symphony performed her Symphony in E minor. One critic wrote that the piece was “faultless” in its passion and restraint. Many of Price’s hundreds of classical compositions were anchored in the tunes and rhythms of classic African-American spirituals. They were performed throughout the United States and Europe. Marian Anderson, one of the world’s great contraltos and herself a breaker of color barriers in a segregated society, included Price’s song “My Soul’s Been Anchored in de Lord” among the pieces she sang at her famous 1939 concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Born in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1887, Price studied music as a child under the guidance of her mother, a schoolteacher and pianist. She went on to study at Boston’s New England Conservatory of Music, a rare opportunity for a black woman in those days. Before returning to Arkansas to marry, she spent two years teaching music at Clark University in Atlanta. Back in Arkansas, she continued to teach and compose. However, because she was African-American, she was refused admission into the Arkansas State Music Teachers Association. Despite the international reputation she earned, her work was knocked well-known in the decades after her death in 1953. In 2009, the new owners of Price’s summer home in Illinois discovered a long-lost trove of her manuscripts. At that time, musicians began to edit, share, and record them, to the delight of new audiences. Music has a way of strengthening a sense of community as it uplifts people’s spirits and brings them together to enjoy an experience transcending the borders of language. Today, as the novel coronavirus continues to spread across the world, people sheltering in place are rediscovering how music can create a joyous shared event even when they are physically apart. With about half of the world’s population under lockdown or quarantine by the beginning of April 2020, professional musicians and singers—and everyday people of all ages and backgrounds—have found joy in using Zoom, Skype, and other types of video and audio technology to make music together while safely socially distanced. As Italy went under lockdown orders, citizens began to sing to one another across their balconies, leaning out their windows, or standing on their roofs. More and more viral videos showed these scenes repeated across Spain, France, India, Israel, the United States, and many other countries. Online orchestras and ensembles that are unable to perform together in the same space have harmonized online through the medium of 21st-century technology, while star-studded benefit galas featuring socially distanced performers raised money to help first responders, patients, and those who had lost jobs and homes in the lengthening shadow of the pandemic. Why we need music nowMusicologists and psychologists point to the desire to bond with other people through music as a central human attribute. Human beings seem to possess an innate need to make connections with others—the kind of face-to-face connection that social media, phone calls, and even video chats can’t provide. Yet when you add music to the online mix, people tend to feel closer. Music can be a powerful counterweight to the widespread feelings of social isolation and alienation, particularly in the present crisis. Research has demonstrated that humans produce more oxytocin, known as a “bonding” hormone, during choral singing or when otherwise sharing music. And with increased oxytocin levels come increased feelings of comfort, safety, and peace. Popular music unites the worldOne World: Together at Home was one of the most-watched—and most moving—benefit concerts in recent memory. While raising money to support food banks and affordable housing, as well as treatment and vaccine development at the World Health Organization, the live-streamed April 18 concert touched the hearts of people all over the world. Favorite artists such as Lady Gaga, Elton John, Alicia Keys, Jennifer Lopez, John Legend, Billie Eilish, and Lizzo created moving moments for viewers, who saw them in a new and personal way as they performed from their homes. The eight-hour production, curated by Lady Gaga and produced by the group Global Citizen, is thought to be the largest musical fundraiser held since 1985’s Live Aid, which supported African famine relief. One World: Together at Home ended up raising more than $127 million for coronavirus relief efforts. Technology democratizes great operaThe Metropolitan Opera in New York, shut down like all other performing arts venues in the city, held its virtual At-Home Gala concert on April 25. The four-hour event featured more than 40 of the biggest names in opera performing via Skype. The event supported the Met’s fundraising campaign to keep its company’s future secure. Music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin conducted and performed on the piano from his Montreal home. Performers included American soprano Renée Fleming, who sang “Ave Maria” from Verdi’s Otello, with her Virginia garden visible in bloom in the background. Soprano Anna Netrebko and tenor Yusif Eyvazov performed from Vienna, with Netrebko delivering a passionate version of Rachmaninoff’s reworking of Georgian folk melodies. From her warm yellow-walled living room in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, soprano Lisette Oropesa performed “En vain j'espère” (“I hope in vain”) from Meyerbeer’s Robert le Diable, with pre-recorded accompaniment by renowned pianist Michael Borowitz. In addition to its artistic quality, the entire production drew rave reviews for the high quality of its technical support, showing how some of the best minds today are stepping up to creative challenges that would have been unthinkable only a few months ago. Alone, a beloved singer brings people togetherAnother remarkable performance set a record for the largest audience to simultaneously view a classical music live stream on YouTube. On Easter Sunday, tenor Andrea Bocelli gave a Music for Hope concert from Milan’s Il Duomo cathedral. Alone except for his socially distanced accompanist at the organ, Bocelli sang sacred pieces composed by Gounod, Mascagni, Rossini, and others, and concluded by standing alone outside on the cathedral steps.

As Bocelli sang the hymn “Amazing Grace,” the camera soared up and out over the architecturally stunning cathedral and across the cityscape of Milan. Bocelli said that he believed in the power of music to bring people together, and his performance touched millions around the world, particularly those in northern Italy enduring some of the most sobering days of the pandemic. There is a variety of jobs for music teachers out there, from band and choir directors, to academy and university instructors, to vocal coaches, just to name a few. One thing all these types of music instructors have in common is the variety of professional organizations available to support them in broadening their networks and keeping their skills sharp. Here are a few of the best known and most respected. 1. MTNA – Close to 150 years of networking and advocacy  The Music Teachers National Association (MTNA) is one of the oldest professional groups for music teachers. Established in 1876, MTNA aims to make music study more accessible while highlighting the value of music to the general public. The organization’s 20,000+ members have access to extensive professional development programs, conduits to new performance opportunities for their students at every stage of proficiency, and numerous opportunities to meet fellow teachers, leaders in the field, and potential mentors. Members may also join active forums meant for specific group subsets, such as college professors or independent instructors. Membership includes a subscription to the organization’s flagship publication, American Music Teacher, as well as an online journal and access to a professional certification program. Members can additionally take advantage of discounted conference and programming fees. Though MTNA works in-depth at the local, state, and national levels, members must typically join at the state or local tier to participate in national programs. Any state chapter may request MTNA funding to pay for the commission of new work from a specific composer. From among these commissions, the national organization selects a recipient of its annual Distinguished Composer of the Year award. Also, the MTNA Foundation Fund accepts donations in support of programs that foster the study and teaching of music, as well as its appreciation, creation, and performance. 2. NAfME – A comprehensive teaching and learning resource Like MTNA, the National Association for Music Education, or NAfME, is more than a century old. Founded in 1907, the group has grown to become one of the largest arts-centered nonprofits in the world. NAfME’s focus is comprehensive, making it the sole organization of its kind devoted to every aspect of music teaching and learning. NAfME works to ensure that music students at every level have the resources and access to instruction with highly trained and responsive teachers while promoting rigorous standards for the teaching and learning of music. Like MTNA, NAfME works at multiple regional levels—local, state, and national—and has built a depth of experience and engagement among its members. Members have access to numerous professional development opportunities, and membership is open to teachers working in any type of organization and in any capacity. Teaching Music magazine is only one of NAfME’s publications aimed at working instructors. NAfME’s members share a concern for diversity, inclusion, and access in the music profession. The organization’s noteworthy advocacy efforts include its regular visits to lawmakers to educate them on the importance of music funding. NAfME’s wealth of online resources, such as webinars and other Internet-based development content, is especially useful as the coronavirus pandemic has reshaped the teaching and learning of all subjects. In addition to its value to professional instructors, NAfME offers several resources for students and parents, many of them freely available on the NAfME website. 3. ISME – Promoting music as everyone’s cultural heritage The International Society for Music Education, or ISME, is the leading global organization devoted to music education. It works to enhance the appreciation of the role of music in creating a vibrant, meaningful cultural life for all the world’s people. Affiliated with the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and its non-governmental organization, the International Music Council, ISME maintains a presence in more than 80 nations. A significant part of its mission focuses on championing the right of every person to an enriching and accessible music education, promoting wide-ranging scholarship in the field of music, and upholding the values of diversity and respect among all cultures. ISME traces its beginnings back to a UNESCO conference in 1953, which ended with participant representatives pledging to promote music education over the long term. Today, the organization, headquartered in Australia, continues to emphasize this mission, functioning as a global networking site for music teachers looking for ways to celebrate the diversity of the world’s music and preserve it as a valuable part of humanity’s cultural heritage. Members can join ISME under any of several categories that meet the needs of individuals, students, current and retired instructors, and groups. The 2020 World Conference was slated for Helsinki in August, but due to the global coronavirus pandemic, the event has been canceled. Even in the face of this unavoidable outcome, organizers are committed to publishing all previously accepted full papers as part of its conference proceedings and repurposing the content of accepted presentations as virtual educational opportunities. Folk songs serve as a repository of musical and cultural history in countries around the world and are among the favorite ways for children and adults to learn music appreciation. In addition, it holds a place in music education through approaches like the Kodály Method, a system of music instruction named for its founder, the renowned 20th century Hungarian composer and musicologist Zoltán Kodály. It relies heavily on folk songs as teaching instruments for musical concepts and basic skills. The idea is that teaching children folk songs from their native lands and those of people throughout the world transmits a rich cultural heritage, along with a knowledge of rhythm, lyricism, structure, and form. Folk songs encompass rural and traditional music that originated in a particular region and that were passed down orally from one generation to another. They have also been collected by musicians and music historians, such as Kodály and his colleague, composer Béla Bartók. They devoted years of their lives to traveling the Hungarian and Romanian countryside to collect thousands of traditional ballads and songs. Similarly, the collection known as the Child Ballads is an anthology of English and Scottish folk music dating from the 17th and 18th centuries and amassed by Harvard professor and folklorist Francis James Child. It features numerous pieces, and modern musicians have adapted many for contemporary audiences. One example is Simon and Garfunkel’s “Scarborough Fair.” Here is a look at a few traditional folk songs that continue to be appreciated to this day: 1. “Greensleeves” The haunting English folk song “Greensleeves,” which dates from sometime in the 16th century, first became a registered ballad in 1580. Its simple and expressive lyrics proclaim the singer’s longing for “Lady Greensleeves,” and he laments that she spurns his affections. For the past four centuries, scholars and the general public have been fascinated by and have speculated over the song’s origins. One theory ascribes the composition of its lyrics, tunes, or both to King Henry VIII, in reference of his mistress and later queen, Anne Boleyn. Most historians and musicologists dispute this idea and instead date the song to the later Elizabethan era. This is in part because “Greensleeves” contains Spanish or Italian musical elements that were unlikely to have reached England until the reign of Queen Elizabeth, the daughter of King Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn. Patriotic Irish musicologist and historian William Henry Grattan Flood included the song in his 1905 book on the history of Irish music, in which he claim that it was of Irish origin. However, Flood was known for attributing numerous elements in anything that he fancied to Ireland, often with no supporting evidence. “Greensleeves” is a unique tune, and its reprise is grounded in a melodic and harmonic formula called romanesca. This composition uses a descending descant musical formula built on sequences of four recurring bass chords that create a fluidly-rolling tune. Romanesca was common for singing poetry in the 16th and 17th centuries. 2. “Sur le Pont d’Avignon”“Sur le Pont d’Avignon” (“On the Bridge of Avignon”) is among the best-known French folk songs and a staple of French children’s music programs. The repetitious lyrics tell of a dance on the Saint Bénezet bridge in Avignon, during which “handsome gentlemen” and “lovely ladies” dance all around while moving in the opposite direction from one another, then reverse direction. Scholars trace the song to the 15th century. The bridge itself is named for a young shepherd who purportedly received a call from heaven to build it, and it was created over the River Rhône in the 12th century. In the late 1600s, a flood swept most of it away, although four arches still stand. These remains are today a UNESCO World Heritage Site. “Sur le Pont d’Avignon” and its idea of dancing on a bridge has been discredited by historians, who point out that it was more likely that people danced under it on an island in the middle of the river. Scholars state that the song was first titled “Sous le Pont d’Avignon,” meaning “under the bridge of Avignon.” 3. “A Csitári Hegyek Alatt”“A Csitári Hegyek Alatt” (“Under the Csitári Mountains” in English) is among the most popular Hungarian folk songs and composed in a style that approaches a traditional mode structure. The song’s lyrics relay a sad tale grounded in themes of love and jealousy.

Kodály included “A Csitári Hegyek Alatt” among his special arrangements of key Hungarian traditional pieces, although he added an additional verse. Additionally, the enduring popularity of the song is evident through its frequent covers by contemporary artists who perform it in various styles, such as the British band Oi Va Voi in their album Laughter Through Tears. Andor Kovács and Gyula Kovács made a jazz version of the song’s tune for their 2000 album Guitar-Drums Battle. |

Photo used under Creative Commons from Marina K Caprara

RSS Feed

RSS Feed